Date and Place: 25 Adar I 5668 (1908), Yafo

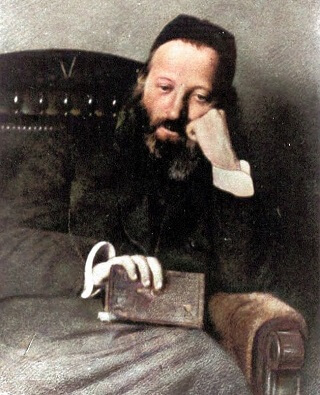

Recipient: Rabbi Yitzchak Yaakov Reines, the Rabbi of Lida and head of the Mizrachi Zionist Movement. Rav Reines had already founded a yeshiva that included secular studies, which was revolutionary in Eastern Europe.

Body: The letter I received from your greatness brought me happiness. I see that the horn of liberation steadily increases in our Desirable Land. Since Hashem has graciously enabled us to be the Land’s builders, we must exert and strengthen ourselves well. Thank G-d, Hashem has liberated His nation, and our Holy Land is in the process of being built and settled before our eyes. We just must pour a spirit of charm and supplication on the settlers of Judea and Jerusalem and connect the hearts of the dispersed, whether geographically or philosophically, to “the home of our lives.” This can bring the flowering of Israel in the light of the Divine Spirit that is upon us in the Holy Land.

I shall address the idea of merging the yeshiva [I am working on] with the beit medrash which Mizrachi plans to establish. This matter is very ready for fruition, for a few reasons. For one, my simple influence caused that many of the Holy Land’s great rabbis realize now that it is incumbent upon us to travel on a new path to strengthen the position of the Torah and belief, in the Holy Land especially, as well as throughout the Jewish world.

Originally, the Shomrei Torah schools planned to go to the extreme and forbid any changes that the times require. Now they have also realized that we need to acquire new strengths for Hashem and His nation. We can connect many people by taking the right steps, especially by the yeshiva’s approach to enlist some of the most talented to deeply investigate spiritual matters and study many areas of academic Jewish studies on a path of sanctity. When this is done, Jewish History, academic study of Tanach, philosophy, and liturgy will no longer be the domain of the destroyers of Torah and belief in Hashem. Rather those who “sit before Hashem” will take the opportunity to uncover secrets in these fields. This will be the greatest contribution to our times’ causes, making it a great salvation for Israel.

Therefore, we must begin preparations to build and prepare that which will be needed after receiving counsel from the wise and G-d fearing. Realize that there is a great obstacle in Eretz Yisrael regarding any innovation to improve the education of G-d-fearing children, especially boys. This is the strongly established, strict ban of the rabbis of the previous generation against any non-Torah study, including foreign languages. Those who know the background understand that at the time it was a necessary step. Our only complaint is that they did not put a time limit on the ban or authorize a beit din in a subsequent generation to end it based on the needs of the time and the rules of the Torah and fear of Hashem. Now people are concerned about complaints of “breaching the fences” by doing something impactful.

However, despite my humble status, I feel compelled because Hashem willed that I accept the hard work of helping guide the New Yishuv, and I have seen that it is critical to bring the remedy before the malady. Therefore, I am working on founding a yeshiva that is broad and great, to plant the tree of life in the heart of the New Yishuv. Then everything will be a blessing. Hopefully, great people will join us in this effort.

We must aspire to greatness, i.e., that the yeshiva will produce our time’s leading rabbis, men great enough to have the foremost impact on the Jewish People, in Israel and the world, through their thoughts and deeds. That requires students to delve deeply into the Torah’s spiritual elements and the knowledge of the ways of Hashem, using old and new methods, coming from the holy source of the Torah of the Land. We hope that it will have such a cultural impact that kings will come to see and bow down before them. There is no limit to what can be achieved within the air of Eretz Yisrael.

Friday, September 23, 2022

Nitzavim – The Last Parsha of 5782

BS”D

Parashat Nitzavim 5782

By HaRav Nachman Kahana

Dear Friends;

This past Wednesday was the 25th of Elul, the anniversary of the onetime event when HaShem created ex nihilo – physical matter from nothing. The day when the Torah begins and HaShem proclaimed “Let there be light”. Six days later on the first of Tishrei year 2, HaShem brought forward the first man and woman.

From then on, all that exists was formed from the original matter that emerged on that first day – day one.

Was the creation of Man a good thing? In Pirkei Avot Hillel says it was not, but Shammai disagreed; the argument ending with both agreeing that from the point of view of mankind it was not such a great idea, but since it is a fait accompli, we must try to be sin free.

As we study the history of mankind and the potential horrors in the future, one tends to agree that HaShem knows what he is doing, but for us it’s a dilemma.

Over the last 20 years I have written variations on the theme of aliya. I have cajoled, threatened, put the fear of punishment into the hearts of good Jews. I have pleaded to people’s sense of history and belonging to HaShem’s Chosen Nation. Not always was the music in my words pleasant to the ear, for that I regret. However, my intentions were first and foremost to save Jewish lives from the degradation of galut, and to rebuild our holy land after 2000 years of anger for our sins of yesterday.

Despite it all, I love every Jew for the simple reason that HaShem loves every Jew. I wish for our small band of tzadikim, not more than 12-13 million men, women and children (much less than the 18 million before the holocaust), to be inscribed in the book of life for health, clarity of mind and good deeds. However, to end this year’s sequence of my traditional warning to come home now would be negligence on my part.

Russia is soon to begin drafting another 300 thousand troops. I believe that the US will have to follow suit and reinstate the selective service act. Your sons and daughters will be taken to military service – yes, daughters too. And when that happens youngsters from the age of 14 until 28 will not be permitted to leave the US, as was the law 60 years ago when I was denied permission to leave for Israel, and I appealed before having to take stronger measures.

Life doesn’t stand still; it is volatile and mercurial with the resha’im dictating the direction of world affairs.

As I have suggested many times in the past, if you cannot come on aliya then send your sons and daughters here. It is not an easy decision to take but it can mean the difference between life and death.

In closing for this year of 5782

On Rosh HaShana HaShem judges individuals and nations. Each individual has an intimate connection with the Creator, so, there are people who have what to be worried about, while others can feel assured of another great year.

Among nations there are those whose destiny is bleak and others who will squeak through one more year, however, Am Yisrael will ascend from strength to strength. How do I know?

The answer is in a little parable:

A passenger plane entered air turbulence and fear gripped the passengers. All aboard showed signs of desperation and fear except for one young girl who stayed calm. When she was asked how she was able to contain herself, she responded quietly, “My father is the pilot”.

Now you can understand why we in Eretz Yisrael can look forward to another great year, getting ever closer to the ge’ula.

Shabbat Shalom & K’tiva vachatima tova

Nachman Kahana

Copyright © 5782/2022 Nachman Kahana

Parashat Nitzavim 5782

By HaRav Nachman Kahana

Dear Friends;

This past Wednesday was the 25th of Elul, the anniversary of the onetime event when HaShem created ex nihilo – physical matter from nothing. The day when the Torah begins and HaShem proclaimed “Let there be light”. Six days later on the first of Tishrei year 2, HaShem brought forward the first man and woman.

From then on, all that exists was formed from the original matter that emerged on that first day – day one.

Was the creation of Man a good thing? In Pirkei Avot Hillel says it was not, but Shammai disagreed; the argument ending with both agreeing that from the point of view of mankind it was not such a great idea, but since it is a fait accompli, we must try to be sin free.

As we study the history of mankind and the potential horrors in the future, one tends to agree that HaShem knows what he is doing, but for us it’s a dilemma.

Over the last 20 years I have written variations on the theme of aliya. I have cajoled, threatened, put the fear of punishment into the hearts of good Jews. I have pleaded to people’s sense of history and belonging to HaShem’s Chosen Nation. Not always was the music in my words pleasant to the ear, for that I regret. However, my intentions were first and foremost to save Jewish lives from the degradation of galut, and to rebuild our holy land after 2000 years of anger for our sins of yesterday.

Despite it all, I love every Jew for the simple reason that HaShem loves every Jew. I wish for our small band of tzadikim, not more than 12-13 million men, women and children (much less than the 18 million before the holocaust), to be inscribed in the book of life for health, clarity of mind and good deeds. However, to end this year’s sequence of my traditional warning to come home now would be negligence on my part.

Russia is soon to begin drafting another 300 thousand troops. I believe that the US will have to follow suit and reinstate the selective service act. Your sons and daughters will be taken to military service – yes, daughters too. And when that happens youngsters from the age of 14 until 28 will not be permitted to leave the US, as was the law 60 years ago when I was denied permission to leave for Israel, and I appealed before having to take stronger measures.

Life doesn’t stand still; it is volatile and mercurial with the resha’im dictating the direction of world affairs.

As I have suggested many times in the past, if you cannot come on aliya then send your sons and daughters here. It is not an easy decision to take but it can mean the difference between life and death.

In closing for this year of 5782

On Rosh HaShana HaShem judges individuals and nations. Each individual has an intimate connection with the Creator, so, there are people who have what to be worried about, while others can feel assured of another great year.

Among nations there are those whose destiny is bleak and others who will squeak through one more year, however, Am Yisrael will ascend from strength to strength. How do I know?

The answer is in a little parable:

A passenger plane entered air turbulence and fear gripped the passengers. All aboard showed signs of desperation and fear except for one young girl who stayed calm. When she was asked how she was able to contain herself, she responded quietly, “My father is the pilot”.

Now you can understand why we in Eretz Yisrael can look forward to another great year, getting ever closer to the ge’ula.

Shabbat Shalom & K’tiva vachatima tova

Nachman Kahana

Copyright © 5782/2022 Nachman Kahana

Torahphobia

by Rabbi Steven Pruzansky

Torahphobia is real, prevalent and sweeping across significant parts of the Jewish world. In particular, it is threatening to collapse Modern Orthodoxy, but fortunately, its antidote is at hand. What is Torahphobia? An example will suffice.

A few days ago, the venerable Israeli radio presenter Aryeh Golan was interviewing (actually, as is his style, castigating) a Member of Knesset running for reelection for the Religious Zionist Party. His questions, such as they were, ran along the lines of: How can you be on the same list with so-and-so who years ago called for a “halachic state”? How can you be on the same list with so-and-so who is a “known homophobe”? The interviewee hesitated, stammered and didn’t offer a cogent answer. In fairness to him, these were not really questions as much as they were readings of counts in an indictment so no answer would have sufficed the interviewer. But this is what the MK could have said:

“Aryeh, you know it is wrong to cherry pick quotations in order to besmirch someone’s reputation, and it is repugnant to characterize a person’s entire life with the tendentious snapshot of “known homophobe.” The latter individual was an activist for Soviet Jewry, instrumental in gaining Natan Sharansky’s release from the gulag, a dedicated public servant for decades and possesses a host of other accomplishments. He is not a “known homophobe” but simply a faithful Jew who wants to strengthen the traditional Jewish family and thereby the Jewish state.”

“But you, Aryeh, present yourself consistently as a Torahphobe. You are afraid of the Torah and its value system. You are afraid that the Torah is true, that God gave the Torah and the land of Israel to the Jewish people, and the implications thereof. You are afraid that God exists, that He bequeathed His moral notions to the Jewish people for our benefit and the benefit of world, afraid that there are mitzvot (commandments, and not merely suggestions of pleasant pieties), afraid that there is such a thing as sin. You are afraid that it is all too real. You are a Torahphobe.”

There is no more grating insult that is lodged against traditional Jews today than that we are homophobes. Besides being false (I have never met anyone who actually fears homosexuals), the accusation is intended to stifle any reasonable discussion of the consequences of implementing the homosexual agenda. Anyone who opposes, for example, the legalization of same-sex marriage (or for that matter, a “pride” club at Yeshiva University) is a “homophobe” who should be scorned, if not tarred and feathered.

These accusers are Torahphobes and we should never hesitate to call them out on it, and repeatedly. Torahphobia is the fear of taking Torah seriously, the fear of perceiving its values as divine, eternal and superior to human values. Torahphobes assume that a national commitment to halachah is the equivalent of Iran. Besides, the fear and ignorance revealed by such a sentiment, they do not realize that brutal enforcement of halachah represents a failure of Jewish society, not its success.

Torahphobes do not really take the Torah seriously, or better said, they only take seriously the parts of Torah that appeal to them. They may observe some mitzvot but not the ones that challenge their secular based value system. They only observe those mitzvot that accord with secular progressive nostrums or the nice, ceremonial and cultural mitzvot that most Jews enjoy. In any clash between their values and Torah values, they fear that embracing the Torah will cause the progressive elites to reject them and so they jettison the Torah. They might sincerely believe that their modern values are the Torah’s values, even more pitiable. They fear that the Torah “might” be true, so they are trying to craft a new Torah for themselves that eliminates certain mitzvot and fabricates new ones, based on pleasant and cherished notions such as equality, inclusiveness, compassion, and the like, all esteemed ideas that nonetheless occasionally conflict with true Torah values.

Certainly, not everyone who holds these opinions is Torahphobic. Some simply do not know any better and assume this is the Torah but many, especially in the Modern Orthodox world do or should know better. We have reached the stage today when, sadly, in any conflict between Modern and Orthodox, the laity opt for Modern and renounce or, better, try to re-define Orthodox. The proponents rationalize these deviations from tradition by declaring that they are trying to prevent violence against certain vulnerable groups, suicides within the group (which itself obviously implicates a range of mental health issues that transcend clubs or societal approbation) or simply to show support for the family that is expressing its distress by staging elaborate same sex weddings and demanding their friends and family join the festivities. Whatever these contentions have, all are psychological manipulations and emotional blackmail. But for Modern Orthodoxy treading down this path is a short term formula for self-destruction.

The laity is faltering and could use some sensitive but determined rabbinic guidance. On the other hand, Modern Orthodox institutions, to their credit, are still holding firm. Witness YU’s ongoing litigation amid the pressure opprobrium it is receiving from some of their own alumni and others. But their commitment is under relentless assault and they require public support to remain steadfast.

A “Pride” club subsidized by Yeshiva University is as sensible as a “Chilul Shabbat Club” that demands public activities on Shabbat or an “intermarriage dating club” that wants to expand the romantic options for the student body. We must have compassion for people’s personal plights and assist them in observing the Torah despite the hardships they feel. But we should reject the notion that they must be accommodated as a group or that, generally, support for traditional family values is somehow hateful. YU does not have to cater to or endorse every sin that people bring with them to college. Indeed, those who want to flaunt and celebrate their sins, whatever they are, can choose any other college in the United States. To want to be “Orthodox” on their terms is quite modern, even understandable, but is also a clear symptom of Torahphobia.

To be sure, we are all guilty of Torahphobia on some level. We are all somewhat afraid of letting go of our practices or beliefs that conflict with the Torah but which we mostly enjoy and sometimes perceive as our self-definition. Everyone has challenges in life. It is axiomatic that we cannot judge another person because we do not stand in their place (Avot 2:4). It is also axiomatic that another person’s challenges seem like a trifle to those who are not challenged in that area, leaving us to wonder why they cannot overcome them (see Masechet Succah 52a). Some are challenged in the realm of arayot in all forms, others in the realm of money, lashon hara, aggression, anger, haughtiness, kindness, love of all Jews and a host of other possibilities. Some people are naturally blessed with no temptation in one area but succumb in other areas. But we all struggle in some vein and it is self-defeating to seek a pass, a license, or public approval of our capitulation. And we were all given by God the gift of repentance that first requires recognition of sin, wrongdoing or shortcomings.

The other day, I was sitting in the Me’arat Hamachpelah (Cave of the Patriarchs) in Hebron, and my mind wandered to Avraham and how he would relate to these modern imbroglios. After all, Avraham lived in most decadent and depraved times and as an Ivri, he stood against the world, its cultural onslaught and moral depredation. He tried to pray for Sodom, or at least comprehend God’s justice in dealing with Sodom, but he didn’t live there, was disappointed when Lot moved there and did not endorse or subsidize their lifestyle because those were the modern mores in his era and the local custom.

We are his heirs and descendants. Avraham possessed not only a deep and abiding faith in God but also an indomitable strength of character that enabled him to stand against the tide of his times even when he was alone and without any public support. His genes – physical and spiritual – give us our foundation, direction and purpose in life. As we enter the Yerach Ha’eitanim, the “month of the mighty” in which our forefathers were born, it behooves us to recapture Avraham’s spirit and animate this generation. Then we will heal ourselves of the rampant, infectious Torahphobia and become passionate Torahphiles, faithful servants of Hashem, and hasten the redemption.

Ktiva va’chatima tova to all!

Torahphobia is real, prevalent and sweeping across significant parts of the Jewish world. In particular, it is threatening to collapse Modern Orthodoxy, but fortunately, its antidote is at hand. What is Torahphobia? An example will suffice.

A few days ago, the venerable Israeli radio presenter Aryeh Golan was interviewing (actually, as is his style, castigating) a Member of Knesset running for reelection for the Religious Zionist Party. His questions, such as they were, ran along the lines of: How can you be on the same list with so-and-so who years ago called for a “halachic state”? How can you be on the same list with so-and-so who is a “known homophobe”? The interviewee hesitated, stammered and didn’t offer a cogent answer. In fairness to him, these were not really questions as much as they were readings of counts in an indictment so no answer would have sufficed the interviewer. But this is what the MK could have said:

“Aryeh, you know it is wrong to cherry pick quotations in order to besmirch someone’s reputation, and it is repugnant to characterize a person’s entire life with the tendentious snapshot of “known homophobe.” The latter individual was an activist for Soviet Jewry, instrumental in gaining Natan Sharansky’s release from the gulag, a dedicated public servant for decades and possesses a host of other accomplishments. He is not a “known homophobe” but simply a faithful Jew who wants to strengthen the traditional Jewish family and thereby the Jewish state.”

“But you, Aryeh, present yourself consistently as a Torahphobe. You are afraid of the Torah and its value system. You are afraid that the Torah is true, that God gave the Torah and the land of Israel to the Jewish people, and the implications thereof. You are afraid that God exists, that He bequeathed His moral notions to the Jewish people for our benefit and the benefit of world, afraid that there are mitzvot (commandments, and not merely suggestions of pleasant pieties), afraid that there is such a thing as sin. You are afraid that it is all too real. You are a Torahphobe.”

There is no more grating insult that is lodged against traditional Jews today than that we are homophobes. Besides being false (I have never met anyone who actually fears homosexuals), the accusation is intended to stifle any reasonable discussion of the consequences of implementing the homosexual agenda. Anyone who opposes, for example, the legalization of same-sex marriage (or for that matter, a “pride” club at Yeshiva University) is a “homophobe” who should be scorned, if not tarred and feathered.

These accusers are Torahphobes and we should never hesitate to call them out on it, and repeatedly. Torahphobia is the fear of taking Torah seriously, the fear of perceiving its values as divine, eternal and superior to human values. Torahphobes assume that a national commitment to halachah is the equivalent of Iran. Besides, the fear and ignorance revealed by such a sentiment, they do not realize that brutal enforcement of halachah represents a failure of Jewish society, not its success.

Torahphobes do not really take the Torah seriously, or better said, they only take seriously the parts of Torah that appeal to them. They may observe some mitzvot but not the ones that challenge their secular based value system. They only observe those mitzvot that accord with secular progressive nostrums or the nice, ceremonial and cultural mitzvot that most Jews enjoy. In any clash between their values and Torah values, they fear that embracing the Torah will cause the progressive elites to reject them and so they jettison the Torah. They might sincerely believe that their modern values are the Torah’s values, even more pitiable. They fear that the Torah “might” be true, so they are trying to craft a new Torah for themselves that eliminates certain mitzvot and fabricates new ones, based on pleasant and cherished notions such as equality, inclusiveness, compassion, and the like, all esteemed ideas that nonetheless occasionally conflict with true Torah values.

Certainly, not everyone who holds these opinions is Torahphobic. Some simply do not know any better and assume this is the Torah but many, especially in the Modern Orthodox world do or should know better. We have reached the stage today when, sadly, in any conflict between Modern and Orthodox, the laity opt for Modern and renounce or, better, try to re-define Orthodox. The proponents rationalize these deviations from tradition by declaring that they are trying to prevent violence against certain vulnerable groups, suicides within the group (which itself obviously implicates a range of mental health issues that transcend clubs or societal approbation) or simply to show support for the family that is expressing its distress by staging elaborate same sex weddings and demanding their friends and family join the festivities. Whatever these contentions have, all are psychological manipulations and emotional blackmail. But for Modern Orthodoxy treading down this path is a short term formula for self-destruction.

The laity is faltering and could use some sensitive but determined rabbinic guidance. On the other hand, Modern Orthodox institutions, to their credit, are still holding firm. Witness YU’s ongoing litigation amid the pressure opprobrium it is receiving from some of their own alumni and others. But their commitment is under relentless assault and they require public support to remain steadfast.

A “Pride” club subsidized by Yeshiva University is as sensible as a “Chilul Shabbat Club” that demands public activities on Shabbat or an “intermarriage dating club” that wants to expand the romantic options for the student body. We must have compassion for people’s personal plights and assist them in observing the Torah despite the hardships they feel. But we should reject the notion that they must be accommodated as a group or that, generally, support for traditional family values is somehow hateful. YU does not have to cater to or endorse every sin that people bring with them to college. Indeed, those who want to flaunt and celebrate their sins, whatever they are, can choose any other college in the United States. To want to be “Orthodox” on their terms is quite modern, even understandable, but is also a clear symptom of Torahphobia.

To be sure, we are all guilty of Torahphobia on some level. We are all somewhat afraid of letting go of our practices or beliefs that conflict with the Torah but which we mostly enjoy and sometimes perceive as our self-definition. Everyone has challenges in life. It is axiomatic that we cannot judge another person because we do not stand in their place (Avot 2:4). It is also axiomatic that another person’s challenges seem like a trifle to those who are not challenged in that area, leaving us to wonder why they cannot overcome them (see Masechet Succah 52a). Some are challenged in the realm of arayot in all forms, others in the realm of money, lashon hara, aggression, anger, haughtiness, kindness, love of all Jews and a host of other possibilities. Some people are naturally blessed with no temptation in one area but succumb in other areas. But we all struggle in some vein and it is self-defeating to seek a pass, a license, or public approval of our capitulation. And we were all given by God the gift of repentance that first requires recognition of sin, wrongdoing or shortcomings.

The other day, I was sitting in the Me’arat Hamachpelah (Cave of the Patriarchs) in Hebron, and my mind wandered to Avraham and how he would relate to these modern imbroglios. After all, Avraham lived in most decadent and depraved times and as an Ivri, he stood against the world, its cultural onslaught and moral depredation. He tried to pray for Sodom, or at least comprehend God’s justice in dealing with Sodom, but he didn’t live there, was disappointed when Lot moved there and did not endorse or subsidize their lifestyle because those were the modern mores in his era and the local custom.

We are his heirs and descendants. Avraham possessed not only a deep and abiding faith in God but also an indomitable strength of character that enabled him to stand against the tide of his times even when he was alone and without any public support. His genes – physical and spiritual – give us our foundation, direction and purpose in life. As we enter the Yerach Ha’eitanim, the “month of the mighty” in which our forefathers were born, it behooves us to recapture Avraham’s spirit and animate this generation. Then we will heal ourselves of the rampant, infectious Torahphobia and become passionate Torahphiles, faithful servants of Hashem, and hasten the redemption.

Ktiva va’chatima tova to all!

The Yishai Fleisher Israel Podcast: Time to Affirm the Covenant

SEASON 2022 EPISODE 38: Rabbi Yishai comes back from Florida and joins Malkah to get ready for Rosh Hashanah with a prayer for strong Jewish leadership. Then, on Table Torah: How Repentance leads to Resurrection - and which leads to Eternity!

What makes us Jewish?

by Rav Binny Freedman

The banging on the door was a shock, but everyone knew what it must mean.

There were three of them standing in the darkened stairwell when they opened the door, in their signature long leather coats. It was the summer of 1938; not an auspicious time to be Jewish in Berlin. Yet Hans was not Jewish; or at least he was not Jewish anymore. He had been named Joseph at birth but had long since forgotten the Jewish grandfather after whom he had been named. His mother had been Jewish but had married a Christian German businessman and had eventually converted to his faith, and Joseph, himself married to a non-Jewish woman had never really considered himself Jewish. But apparently the Nazis begged to differ.

Someone had informed the authorities that he had been born of a Jewish mother, and his presence was kindly requested at Police headquarters. He was told he need not bring any belongings; it was simply an invitation for routine questioning. But there was no mistaking the nature of this invitation; he was not being asked; he was being ordered. And seventy years later, his daughter still remembers the fear in his eyes and the tremble in his voice when he gave her a hug and told her to go back to sleep.

They never saw him again. From eyewitness accounts after the war, they know he was taken to Gestapo headquarters and beaten and tortured for two days, though it remains unclear what exactly they wanted of him. On the third day, he was sent to Dachau where he eventually died of exposure when a Nazi guard forced him to run and jump naked in the snow for an entire afternoon …

Fast forward some seventy years; again, the middle of the night. Surrounded by Arabs in the ancient city of Shechem (Nablus) a small group of Jews has come to pray at the ancient gravesite of … Joseph.

Although it is a somewhat dangerous proposition for Jews to enter the Arab city of Shechem deep in the heart of the Palestinian Authority, the army allows it under certain circumstances, once a month, in the middle of the night, when there are presumably no Arabs on the streets.

Yoseph, Yaakov’s beloved son in the Torah, has come to represent the Jew in exile, both for his ability to maintain his Jewish identity as a lone Jewish slave in the heart of ancient pagan Egypt, as well as for the fact that his sons, Menashe and Ephraim, were the first Jews born in exile.

And this night, no one is afraid, for this is a very special group of people. Known as the B’nei Menashe, they hail from India and Nepal, and believe they are descended of the lost tribe of Menashe son of Yosef.

Exiled as part of the great exile of the ten tribes twenty-seven hundred years ago, when Assyria conquered Northern Israel, they are fulfilling a twenty seven-hundred-year-old dream; this night they are re-uniting with their long lost ancestor Joseph after nearly three millennium of dreaming ….

What makes us Jewish? Is it a shared system of beliefs? What if someone chooses not to adopt or adhere to those beliefs? Can a person decide not to be Jewish? Twenty-five hundred years ago, seventy years deep into the Babylonian exile, the sage Ezra chastises the Jews for wanting to be more Babylonian than the Babylonians:

“What is in your mind will never happen: the thought: ‘Let us be like the Nations…’…”

It seems the Jews do not want to be Jews; they want to remain Babylonian. And that, says Ezra cannot, will not ever be. But why not? Maimonides makes it very clear (Hilchot Teshuva chap. 5) that one of the essential principals of Judaism is Free Will; despite G-d’s Omnipotence, we were created with the freedom to choose. And we are held accountable for those choices. And yet, it appears we cannot choose not to be Jewish.

The Gemara (Sanhedrin 44a) makes it quite clear that no matter what mistakes a Jew makes, and whatever his transgressions, he or she remains a Jew.

This week, our portion Nitzavim, makes reference to this question.

Moshe, in sharing his final words with the Jewish people reminds them of the Covenant they accepted at Sinai, renewing it for all time and for all Jews forever:

“It is not with you alone that I am making this Covenant, but with whoever is standing here today, and with whoever is not here with us today …” (Devarim 29:13-14)

And since the entire Jewish people at the time were present, the sages conclude it was a covenant made for every Jew that will ever be born! But how can we be held responsible for a promise made by our ancestors before we were ever born??

And why does G-d, as the great sage Ezra suggests, promise we will never be able to hide; we will always be the Jewish people?

Jewish tradition suggests that we actually were all at Sinai. The Midrash (Shemot Rabbah 28:6) tells us that the souls of every Jew yet to be born, were actually present at Sinai, thus, we actually did accept the covenant out of choice when we said (Exodus chap. 24) “Na’aseh ve’nishma”; “We will do and we will understand…”.

But what does this actually mean?

In fact, there are really two parts to who we are. There is the body, the physical reality we each occupy in this world. And then there is the soul; our spiritual reality. The definition of all things physical, is that they are limited. Hence, as Maimonides suggests, G-d cannot be physical, because G-d has no limits. Everything physical eventually ends, hence the body will eventually fail us, and will return to the ground from whence we were created, the phenomenon we call death.

Yet, there is also a spiritual essence to who we are; all the aspects of our selves which have no limits: the capacity to love and to give, to care and to share, which are endless. And there is no reason to assume this nonphysical endless part of our selves has to end.

Most people who share this belief think of this idea in terms of each person having a soul. But a person does not have a soul; a person is a soul. The essence of a soul is our will, or ratzon, and this will, cultivated properly, is what allows us all to be who we are meant to be. And it is the soul that we are, that drives the physical aspect of ourselves to make a difference in this world.

Perhaps there are two aspects to being a Jew. There is the system of beliefs and behaviors every individual Jew is responsible to uphold. But there is also the driving force that represents the wellspring of the Jewish people and the essence of our ability to change the world, and this, suggests Jewish tradition, will never cease. Because the world needs this will, and this message to become the place it was always meant to be.

A Jew can choose not to behave as a Jew and he or she can mask the physical role they play so that they are barely recognizable as a Jew. But no Jew will ever cease to be a Jew, any more than a person can cease to be artistic, or musical, or a child born in France. And recognizing that reality is what allows us to become a force for good and meaning in this world.

Indeed, this is at the heart of the days of awe that are soon upon us.

Rambam (Hilchot Tshuva 1:1) suggests that the central mitzvah of teshuva is Vidui: to be admit, or confess, before Hashem. But the word Modeh also means to be thankful. Sometimes people have a hard time saying thank you, because they do not want to be beholden; to owe.

But in truth we all are in debt, and we all owe. We owe all those who have given so much that we might live the lives we live, and we owe our creator the life we have been given. Which also means we owe ourselves; we owe the selves Hashem (G-d) has created us to be. We owe it to ourselves to become the best selves we can be, because the world needs us to do that.

May Hashem bless us all to live up to our selves so that this year can be filled with the peace and joy, love and harmony we all yearn for.

Wishing you all a sweet happy and healthy new year,

Best wishes for a Ktivah vechatimah Tovah.

The banging on the door was a shock, but everyone knew what it must mean.

There were three of them standing in the darkened stairwell when they opened the door, in their signature long leather coats. It was the summer of 1938; not an auspicious time to be Jewish in Berlin. Yet Hans was not Jewish; or at least he was not Jewish anymore. He had been named Joseph at birth but had long since forgotten the Jewish grandfather after whom he had been named. His mother had been Jewish but had married a Christian German businessman and had eventually converted to his faith, and Joseph, himself married to a non-Jewish woman had never really considered himself Jewish. But apparently the Nazis begged to differ.

Someone had informed the authorities that he had been born of a Jewish mother, and his presence was kindly requested at Police headquarters. He was told he need not bring any belongings; it was simply an invitation for routine questioning. But there was no mistaking the nature of this invitation; he was not being asked; he was being ordered. And seventy years later, his daughter still remembers the fear in his eyes and the tremble in his voice when he gave her a hug and told her to go back to sleep.

They never saw him again. From eyewitness accounts after the war, they know he was taken to Gestapo headquarters and beaten and tortured for two days, though it remains unclear what exactly they wanted of him. On the third day, he was sent to Dachau where he eventually died of exposure when a Nazi guard forced him to run and jump naked in the snow for an entire afternoon …

Fast forward some seventy years; again, the middle of the night. Surrounded by Arabs in the ancient city of Shechem (Nablus) a small group of Jews has come to pray at the ancient gravesite of … Joseph.

Although it is a somewhat dangerous proposition for Jews to enter the Arab city of Shechem deep in the heart of the Palestinian Authority, the army allows it under certain circumstances, once a month, in the middle of the night, when there are presumably no Arabs on the streets.

Yoseph, Yaakov’s beloved son in the Torah, has come to represent the Jew in exile, both for his ability to maintain his Jewish identity as a lone Jewish slave in the heart of ancient pagan Egypt, as well as for the fact that his sons, Menashe and Ephraim, were the first Jews born in exile.

And this night, no one is afraid, for this is a very special group of people. Known as the B’nei Menashe, they hail from India and Nepal, and believe they are descended of the lost tribe of Menashe son of Yosef.

Exiled as part of the great exile of the ten tribes twenty-seven hundred years ago, when Assyria conquered Northern Israel, they are fulfilling a twenty seven-hundred-year-old dream; this night they are re-uniting with their long lost ancestor Joseph after nearly three millennium of dreaming ….

What makes us Jewish? Is it a shared system of beliefs? What if someone chooses not to adopt or adhere to those beliefs? Can a person decide not to be Jewish? Twenty-five hundred years ago, seventy years deep into the Babylonian exile, the sage Ezra chastises the Jews for wanting to be more Babylonian than the Babylonians:

“What is in your mind will never happen: the thought: ‘Let us be like the Nations…’…”

It seems the Jews do not want to be Jews; they want to remain Babylonian. And that, says Ezra cannot, will not ever be. But why not? Maimonides makes it very clear (Hilchot Teshuva chap. 5) that one of the essential principals of Judaism is Free Will; despite G-d’s Omnipotence, we were created with the freedom to choose. And we are held accountable for those choices. And yet, it appears we cannot choose not to be Jewish.

The Gemara (Sanhedrin 44a) makes it quite clear that no matter what mistakes a Jew makes, and whatever his transgressions, he or she remains a Jew.

This week, our portion Nitzavim, makes reference to this question.

Moshe, in sharing his final words with the Jewish people reminds them of the Covenant they accepted at Sinai, renewing it for all time and for all Jews forever:

“It is not with you alone that I am making this Covenant, but with whoever is standing here today, and with whoever is not here with us today …” (Devarim 29:13-14)

And since the entire Jewish people at the time were present, the sages conclude it was a covenant made for every Jew that will ever be born! But how can we be held responsible for a promise made by our ancestors before we were ever born??

And why does G-d, as the great sage Ezra suggests, promise we will never be able to hide; we will always be the Jewish people?

Jewish tradition suggests that we actually were all at Sinai. The Midrash (Shemot Rabbah 28:6) tells us that the souls of every Jew yet to be born, were actually present at Sinai, thus, we actually did accept the covenant out of choice when we said (Exodus chap. 24) “Na’aseh ve’nishma”; “We will do and we will understand…”.

But what does this actually mean?

In fact, there are really two parts to who we are. There is the body, the physical reality we each occupy in this world. And then there is the soul; our spiritual reality. The definition of all things physical, is that they are limited. Hence, as Maimonides suggests, G-d cannot be physical, because G-d has no limits. Everything physical eventually ends, hence the body will eventually fail us, and will return to the ground from whence we were created, the phenomenon we call death.

Yet, there is also a spiritual essence to who we are; all the aspects of our selves which have no limits: the capacity to love and to give, to care and to share, which are endless. And there is no reason to assume this nonphysical endless part of our selves has to end.

Most people who share this belief think of this idea in terms of each person having a soul. But a person does not have a soul; a person is a soul. The essence of a soul is our will, or ratzon, and this will, cultivated properly, is what allows us all to be who we are meant to be. And it is the soul that we are, that drives the physical aspect of ourselves to make a difference in this world.

Perhaps there are two aspects to being a Jew. There is the system of beliefs and behaviors every individual Jew is responsible to uphold. But there is also the driving force that represents the wellspring of the Jewish people and the essence of our ability to change the world, and this, suggests Jewish tradition, will never cease. Because the world needs this will, and this message to become the place it was always meant to be.

A Jew can choose not to behave as a Jew and he or she can mask the physical role they play so that they are barely recognizable as a Jew. But no Jew will ever cease to be a Jew, any more than a person can cease to be artistic, or musical, or a child born in France. And recognizing that reality is what allows us to become a force for good and meaning in this world.

Indeed, this is at the heart of the days of awe that are soon upon us.

Rambam (Hilchot Tshuva 1:1) suggests that the central mitzvah of teshuva is Vidui: to be admit, or confess, before Hashem. But the word Modeh also means to be thankful. Sometimes people have a hard time saying thank you, because they do not want to be beholden; to owe.

But in truth we all are in debt, and we all owe. We owe all those who have given so much that we might live the lives we live, and we owe our creator the life we have been given. Which also means we owe ourselves; we owe the selves Hashem (G-d) has created us to be. We owe it to ourselves to become the best selves we can be, because the world needs us to do that.

May Hashem bless us all to live up to our selves so that this year can be filled with the peace and joy, love and harmony we all yearn for.

Wishing you all a sweet happy and healthy new year,

Best wishes for a Ktivah vechatimah Tovah.

G-d “hears the sound of His People Israel’s shofar blowing with mercy

by HaRav Dov Begon

Rosh HaYeshiva, Machon Meir

Rosh Hashanah has the aspect of being the start of the entire year. As Rabbi Shneur Zalmen of Liadi explained, just as a person has a head and a brain that influence and sustain the entire body, so is Rosh Hashanah a sort of brain for the year, influencing the entire year. And just as one’s head, brain, and heart have to be pure and righteous, so must we on Rosh Hashanah purify ourselves by way of repentance and good deeds, good thoughts, and good speech. Through this, we influence the entire year, making it good and sweet. Especially important is the mitzvah of hearing the Shofar (whose very name recalls “improvement” [shipur]). The Shofar hints at and teaches us how we must relate properly and constructively to the Day of Judgment and to Strict Judgment.

And how is that? The shofar blasts fall into three categories, alluding to divine kindness, strict judgment, and mercy. The first blast, the teki’ah, alludes to kindness. It is a simple sound, and where kindness exists, all is simple. In the middle comes the teruah, consisting of broken blasts, the sound of loud sobbing, sighing, weeping, and wailing. These allude to strict judgment and to life’s hardships. In the end, comes another tekiah, a simple blast alluding to mercy and love. We hear how the blasts are joined together until one can hear the kindness within strict judgment, the light within the darkness, the sweetness within the bitter. We get a sense of how G-d really is “good to all, with His mercy governing all His works” (Tehilim 145:9). Pondering and listening to the sweet, remarkable shofar blasts arouses and strengthens within us the belief that despite everything, when all is said and done, “One higher than the high is watching over us” (Kohelet 5:7), and there is no one else but Him. The L-rd G-d of Israel is King, and His monarchy rules over all. By such means, a Jew purifies his mind and heart on Rosh Hashanah, and this day shines upon the entire year.

Today, let the old year and its curses end and let the new year and its blessings begin. This year has been hard and painful for the Jewish People. The sound of the “teruah”, the sound of weeping and sighing, was the lot of so many innocent Jews expelled from their homes. The pain and suffering, doubts, and worries were the lots of many other Jews as well, who felt the enormity of the pain. On Rosh Hashanah, we have to arouse ourselves and grow stronger through the shofar blasts. We have to hear the teki’ot preceding and following the teruah. We have to recognize that G-d, who hears our prayers, mercifully hears the sound of the teruah, as we note in the Rosh Hashanah Shemoneh Esreh: “Blessed be G-d… who hears the sound of the teruah of His people Israel, with mercy.”

With blessings for a good, sweet year, and a ketivah vechatimah tovah.

Looking forward to salvation,

Rosh HaYeshiva, Machon Meir

Rosh Hashanah has the aspect of being the start of the entire year. As Rabbi Shneur Zalmen of Liadi explained, just as a person has a head and a brain that influence and sustain the entire body, so is Rosh Hashanah a sort of brain for the year, influencing the entire year. And just as one’s head, brain, and heart have to be pure and righteous, so must we on Rosh Hashanah purify ourselves by way of repentance and good deeds, good thoughts, and good speech. Through this, we influence the entire year, making it good and sweet. Especially important is the mitzvah of hearing the Shofar (whose very name recalls “improvement” [shipur]). The Shofar hints at and teaches us how we must relate properly and constructively to the Day of Judgment and to Strict Judgment.

And how is that? The shofar blasts fall into three categories, alluding to divine kindness, strict judgment, and mercy. The first blast, the teki’ah, alludes to kindness. It is a simple sound, and where kindness exists, all is simple. In the middle comes the teruah, consisting of broken blasts, the sound of loud sobbing, sighing, weeping, and wailing. These allude to strict judgment and to life’s hardships. In the end, comes another tekiah, a simple blast alluding to mercy and love. We hear how the blasts are joined together until one can hear the kindness within strict judgment, the light within the darkness, the sweetness within the bitter. We get a sense of how G-d really is “good to all, with His mercy governing all His works” (Tehilim 145:9). Pondering and listening to the sweet, remarkable shofar blasts arouses and strengthens within us the belief that despite everything, when all is said and done, “One higher than the high is watching over us” (Kohelet 5:7), and there is no one else but Him. The L-rd G-d of Israel is King, and His monarchy rules over all. By such means, a Jew purifies his mind and heart on Rosh Hashanah, and this day shines upon the entire year.

Today, let the old year and its curses end and let the new year and its blessings begin. This year has been hard and painful for the Jewish People. The sound of the “teruah”, the sound of weeping and sighing, was the lot of so many innocent Jews expelled from their homes. The pain and suffering, doubts, and worries were the lots of many other Jews as well, who felt the enormity of the pain. On Rosh Hashanah, we have to arouse ourselves and grow stronger through the shofar blasts. We have to hear the teki’ot preceding and following the teruah. We have to recognize that G-d, who hears our prayers, mercifully hears the sound of the teruah, as we note in the Rosh Hashanah Shemoneh Esreh: “Blessed be G-d… who hears the sound of the teruah of His people Israel, with mercy.”

With blessings for a good, sweet year, and a ketivah vechatimah tovah.

Looking forward to salvation,

With Love of Israel,

Shabbat Shalom.

Thursday, September 22, 2022

Palestinians Cuddle up with Arabs Who Kill Palestinians

by Khaled Abu Toameh

A report published on September 18 revealed that 638 Palestinians have been tortured to death by Syrian intelligence officers in the past few years. The victims include 37 women. The Action Group for Palestinians of Syria also revealed that 4,121 Palestinians have been killed in Syria since the beginning of the civil war there. The fate of 1,797 Palestinian detainees, including 110 women, remains unknown. Pictured: The Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp, near Damascus, on May 22, 2018, days after Assad regime forces regained control over the camp. (Photo by Louai Beshara/AFP via Getty Images)

A report published on September 18 revealed that 638 Palestinians have been tortured to death by Syrian intelligence officers in the past few years. The victims include 37 women, according to the report by the Action Group for Palestinians of Syria (AGPS), a human rights watchdog that monitors the situation of Palestinian refugees in war-torn Syria.

The group called on the Syrian authorities to disclose the status of hundreds of Palestinians who are being held in Syrian prisons and whose fate remains unknown. "What is happening inside the Syrian detention centers against the Palestinians is a war crime by all standards," it said.

AGPS also revealed that 4,121 Palestinians have been killed in Syria since the beginning of the civil war there.

"AGPS data indicates that 79% of the Palestinians of Syria killed since the outbreak of the conflict are civilians.

Continue Reading Article

- A report published on September 18 revealed that 638 Palestinians have been tortured to death by Syrian intelligence officers in the past few years. The victims include 37 women.

- "What is happening inside the Syrian detention centers against the Palestinians is a war crime by all standards." — Action Group for Palestinians of Syria (AGPS), September 18, 2022.

- AGPS also revealed that 4,121 Palestinians have been killed in Syria since the beginning of the civil war there.

- The fate of 1,797 Palestinian detainees, including 110 women, remains unknown despite repeated appeals to the Syrian authorities.

- By rushing to embrace the regime of Syrian President Bashar Assad, Hamas, whose leaders control the Gaza Strip from their luxurious villas, hotel suites and spas in Qatar and Turkey, has again shown its contempt for the Palestinians and other Arabs who have fallen victim to the atrocities committed by the Syrian authorities, especially over the past decade.

- Iran's mullahs want to make sure that their terrorist proxies and the Assad regime remain on good terms. The mullahs are hoping that the renewal of ties between Hamas and Syria will strengthen the Iranian-led "axis of resistance" in the Middle East. The "axis of resistance" refers to an anti-Western/anti-Israeli/anti-Saudi political and military alliance between Iran, the Palestinian terrorist groups Hamas and Islamic Jihad, the Syrian regime and Hezbollah.

- Hamas... apparently has no problem embracing an Arab regime that has so much Palestinian blood on its hands.

- The Hamas embrace of the Assad regime is yet another example of how Palestinian leaders care nothing about their own people, let alone the lives of other Arabs.

- The leaders of Hamas, who are living the good life in Qatar and Turkey, are much more interested in stuffing their coffers with money from the mullahs in Iran than in seeing the suffering of their people in the Gaza Strip or in any Arab country, including Syria.

- The leaders of the Palestinian Authority are not much different. They too are preoccupied with looking after their personal interests and making sure that they remain in power forever.

- Shortly, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas will head to the United Nations General Assembly to spew yet more venom against Israel. The plight of his people in Syria and other Arab countries will be at the very bottom of his list of priorities, if at all. Like Hamas, Abbas too does not seem to care if his people are being slaughtered by an Arab dictatorship.

A report published on September 18 revealed that 638 Palestinians have been tortured to death by Syrian intelligence officers in the past few years. The victims include 37 women. The Action Group for Palestinians of Syria also revealed that 4,121 Palestinians have been killed in Syria since the beginning of the civil war there. The fate of 1,797 Palestinian detainees, including 110 women, remains unknown. Pictured: The Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp, near Damascus, on May 22, 2018, days after Assad regime forces regained control over the camp. (Photo by Louai Beshara/AFP via Getty Images)

A report published on September 18 revealed that 638 Palestinians have been tortured to death by Syrian intelligence officers in the past few years. The victims include 37 women, according to the report by the Action Group for Palestinians of Syria (AGPS), a human rights watchdog that monitors the situation of Palestinian refugees in war-torn Syria.

The group called on the Syrian authorities to disclose the status of hundreds of Palestinians who are being held in Syrian prisons and whose fate remains unknown. "What is happening inside the Syrian detention centers against the Palestinians is a war crime by all standards," it said.

AGPS also revealed that 4,121 Palestinians have been killed in Syria since the beginning of the civil war there.

"AGPS data indicates that 79% of the Palestinians of Syria killed since the outbreak of the conflict are civilians.

Continue Reading Article

“Welcome…to yourself!”

by Rabbi Pinchas Winston

In memory of Ya’akov ben Aharon HaKohen, zt”l, who went to his world at a very young age, but not before inspiring those who knew him with his devotion to God and His Torah. He accepted his situation and suffering with love, and his emunah never wavered. He will be a meilitz yoshar for Klal Yisroel.

Friday Night

This is not my story, but it could be anybody’s.

It was the first day of Selichos, Motzei Shabbos, 12:30 am. I never enjoyed being up so late, and I never looked forward to having to saying Selichos at that time of night. But there I was once again with everyone else in my minyan, saying Ashrei to kick off another year of many days of long dovening. It made me more tired just thinking about it.

But then something happened to me, and quite unexpectedly. I don’t remember during which verse of Ashrei, but something “touched” me inside, and all of a sudden, my whole mood changed. Within a moment this feeling welled up inside of me, and the next thing I knew I was fighting back tears, totally unexpected tears, and I hoped no one else noticed. Suddenly, I had this second wind and all of my tiredness just…vanished.

For three weeks I had dutifully listened to the shofar being blown after Shacharis, and said L’Dovid like everyone else. The shofar, if blown well, has its own power to get “inside” you. A trumpet sounds regal, ceremonious. A shofar sounds like a heart crying and personally, that gets to me, at least a little.

But not once did a shofar blowing ever make feel what I felt that first night of Selichos. It even happened a few more times that night, and by the time Selichos was over, I was charged up. I was definitely still tired, but another part of me was wide awake and feeling the serious of the time of year. It was over a week until Rosh Hashanah and I was already connected. I wondered how long that would last.

Normally I might have walked home with a neighbor, but I made a point of slipping out quickly to walk on my own. I was curious about the experience I had and wanted to figure it out. It was like there was this other side of me that I had never met, and I wanted to know more about him.

The next day I spoke about it with my chavrusa. He listened the entire time without saying a word, just smiling the whole time. When I finished, I asked him what his smile was about, and he told me something I have never forgotten, even decades later.

“That was no other side of you,” he told me. “That was your soul. Your body is like a hard stone mountain, and your soul is like the magma inside of it. When enough pressure builds up inside, the soul, like the magma, blows the top off the mountain…your body that is…and reveals the inside to the outside. That experience may have been new to you that night, but you’ve been carrying it around with you your entire life. It just finally made it out. You finally made it out.” And then, grinning once again, he said, “Welcome…to yourself!”

Shabbos Day

I THOUGHT ABOUT his words. “But why now?” I asked my chavrusa, “What triggered it all of a sudden?”

“I’m not sure,” he said. “Only you can really answer that question. Was there anything special that happened just before that?”

“Are you kidding?” I said. “I was so tired and just wanted to go to bed already.”

“That sure is spiritual,” he teased.

But as he did, something inside me caught my attention. I had asked the question to him, but seemed to be answering it myself, from the inside. I don’t even know what made me think of it, but once I did, it made sense to me. At the time of the incident, I had thought little of it, but I guess it left an impression on me, or rather, inside of me.

My wife and I had been guests for Shabbos lunch at our neighbor’s. It was Parashas Ki Savo, and the host, while talking about the curses found in the parsha, spoke about hester panim, the hiding of God’s face. He explained something that in all my years I had never heard, and used a moving story to make his point.

The story was about two brothers, and how the younger of the two liked to tag along with the older brother and his friends, especially on the day they decided to play hide-and-go-seek. The older brother would have said no, but their father insisted that the younger brother be allowed to join them.

As everyone ran to hide in one place or another, the younger brother did the same and waited to be found. But instead, his brother and friends used the opportunity to ditch the tag-along, who waited in vain to be found. When no one came looking for him for a long while and he could no longer hear any voices, he came out to investigate.

He didn’t understand at first what had happened, but it slowly dawned on him that while he had hidden, everyone else had left. Feeling abandoned, he began to cry and went home.

When he was close enough to his home, his father recognized his crying and came running out to see what had happened. The younger brother explained everything to his father in between his sobbing, after which his father began to cry as well. This distracted the son who then stopped crying as his father began to cry even harder.

Confused, the boy asked his father, “Abba, why are you crying? It happened to me, not to you!”

The tearful father said, “Because my son, until now I did not understand. You hid from the other boys, but not because you didn’t want to be found. You wanted the others to come looking for you, but was saddened when they didn’t. I realize now that the same can be said for God. He has hidden Himself, but not so we shouldn’t find Him, as many might think. But to see if care enough to go looking for Him…and yet so few do. How sad He must be!”

As the host finished his dvar Torah, my wife turned to look at me to see if I had enjoyed the analogy as much as she had, and was surprised to see a tear in my eye. What she did not know until later was that the story had happened to me with my older brother, several decades back. But my father had not heard me or come out to comfort me like in the story. Nevertheless, the story hit home and gave new meaning to an incident from my past. For a short while, I again felt the same pain, but this time I transferred it to God.

After all, my incident had experienced been an isolated incident, but it has been happening to God daily for thousands of years now. I was able to move on, but God has to deal with it every day. My brother and I eventually became the best of friends, but so much of mankind has turned its back on God. I found myself feeling very sad for Him.

We enjoyed the rest of seudah with our hosts and later returned home. The story, I had assumed, had simply become a memory.

Shalosh Seudot

WE ARE NOT always aware of the things that change us. Sometimes the subtlest of ideas can have the profoundest of impacts on a person, for good and unfortunately, for bad. Sometimes ideas can be planted as “seeds” in our minds, and take root and sprout on their own over time, changing us into better or, God forbid, worse people.

My neighbor may never know it, but his little story was such seed for good. It took a past sensitivity of mine that I had forgotten about and turned into one in the Present. But not for me this time, but for God. It enhanced my relationship with Him in a way I had not done before that.

What incredible hashgochah pratis—divine providence…that we were invited for a Shabbos seudah…the Shabbos of Parashas Ki Savo…which led to a dvar Torah with a story that seemed custom-designed for me. And it was amazing hashgochah that the first Selichos was later that night, while I was still impacted by the story. As a result, when I said Ashrei that Selichos night, I already felt a connection to God, and the sadness I had felt that afternoon once again moved me emotionally.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that it wasn’t just sadness I was feeling for God. It was also love, a more intense love. I mean, I had wanted to believe that I had always loved God, but the “sympathy” I felt for Him somehow made Him seem less far away…more accessible.

Or maybe it was the other way around. Maybe it made me less far away…more accessible. Until that day, I lived my Judaism from day to day, trying to be sincere but often falling short. Life can be very tiring and very distracting, especially when it comes to do mitzvos properly. I always knew God was there, you know, “there.”

My chavrusa thought that was really going on was that God had reached out to me. He thought that, once God saw me reach out to Him, He reached out to me. As the Gemora says, “Someone who comes to sanctify themself a little, they sanctify him a lot” (Yoma 38b). I told him that I really liked that idea.

The story, and the idea behind it made God seem more here to me, more a part of my everyday life. It talked to my soul and kind of neutralized my body in the process. The feeling of love just automatically resulted, and it spilled over into the way I learned, prayed, and did the rest of my mitzvos.

Who would have thought it? But then I began learning the next parsha, Nitzavim, and even that seemed to talk directly to me now. And all the promises that God made about bringing all of us back to Eretz Yisroel seemed so much more real, as if they were being made now. But the verse that really made me stop and think was this one:

And God, your God, will circumcise your heart and the heart of your offspring, [so that you may] love God your God with all your heart and with all your soul, for the sake of your life. (Devarim 30:6)

“Wow…” I said to myself softly, feeling all emotional again. I thought, “Did this not just happen to me?”

Though I had read that verse countless times before, it was always as if it was going to happen to some future generation, not mine. Not now. Now I felt blessed that it had happened to me, and wondered how many others it was happening to as well.

Ain Od Milvado, Part 19

IT ALSO GAVE me a new perspective on the following:

You have been shown, in order to know that God, He is God; ain od Milvado—there is none else besides Him. (Devarim 4:35)

I always had two questions about this. First of all, why does God have to show us anything to prove Himself? Humans are limited and have to prove they can do what they say. But God is unlimited, and by definition He can do anything He says.

Secondly, they were shown, not us. And just reading about it doesn’t do very much to fight back atheism and agnosticism, or to help with the lack of zealousness that results from not taking God seriously. Just as they needed to see to believe that God is the only one, we need to see it as well, probably now more than ever.

But we do. All around us is evidence of God and His providence…if we’re open to see it. It is amazing how we can look at something one moment and see it one way, and then have an experience that shows us the same thing the next moment in different, sometimes even an opposite way. The verse is telling us that God is showing us things so that we can know He is the only one. We just have to learn to see it.

As for the first question, He doesn’t need to prove Himself. We need to prove Him to ourselves because of our own fears and insecurities. We doubt God but not because God is doubtful, but because we don’t make enough effort to work out why He is not. The verse is telling us that God knows this and even accommodates us. “What a chesed!” I thought to myself, and that only made me love God more.

With Rosh Hashanah just a few days away, I never felt more ready. In fact, I even looked forward to all the dovening coming up, something new for me. I used to look at it as just something I had to do at this time of year. I was beginning to look at it as something I wanted to do at this time of year. I planned to use it as an opportunity to expand upon what I had experienced over the last week.

And if my chavrusa was correct, and the Gemora seems to say that he is, I can expect God to do the same. Rosh Hashanah is not a one-way street. It is the time that the Jewish people run towards God, and God runs towards the Jewish people. As God says, “I am to My beloved, and My beloved is to Me” (Shir HaShirim 6:3).

I can’t wait.

Thanks for another year of Perceptions reading. I hope you’ll keep reading in the new year, b”H.

Kesivah uChasimah Tovah.

In memory of Ya’akov ben Aharon HaKohen, zt”l, who went to his world at a very young age, but not before inspiring those who knew him with his devotion to God and His Torah. He accepted his situation and suffering with love, and his emunah never wavered. He will be a meilitz yoshar for Klal Yisroel.

Friday Night

This is not my story, but it could be anybody’s.

It was the first day of Selichos, Motzei Shabbos, 12:30 am. I never enjoyed being up so late, and I never looked forward to having to saying Selichos at that time of night. But there I was once again with everyone else in my minyan, saying Ashrei to kick off another year of many days of long dovening. It made me more tired just thinking about it.

But then something happened to me, and quite unexpectedly. I don’t remember during which verse of Ashrei, but something “touched” me inside, and all of a sudden, my whole mood changed. Within a moment this feeling welled up inside of me, and the next thing I knew I was fighting back tears, totally unexpected tears, and I hoped no one else noticed. Suddenly, I had this second wind and all of my tiredness just…vanished.

For three weeks I had dutifully listened to the shofar being blown after Shacharis, and said L’Dovid like everyone else. The shofar, if blown well, has its own power to get “inside” you. A trumpet sounds regal, ceremonious. A shofar sounds like a heart crying and personally, that gets to me, at least a little.

But not once did a shofar blowing ever make feel what I felt that first night of Selichos. It even happened a few more times that night, and by the time Selichos was over, I was charged up. I was definitely still tired, but another part of me was wide awake and feeling the serious of the time of year. It was over a week until Rosh Hashanah and I was already connected. I wondered how long that would last.

Normally I might have walked home with a neighbor, but I made a point of slipping out quickly to walk on my own. I was curious about the experience I had and wanted to figure it out. It was like there was this other side of me that I had never met, and I wanted to know more about him.

The next day I spoke about it with my chavrusa. He listened the entire time without saying a word, just smiling the whole time. When I finished, I asked him what his smile was about, and he told me something I have never forgotten, even decades later.

“That was no other side of you,” he told me. “That was your soul. Your body is like a hard stone mountain, and your soul is like the magma inside of it. When enough pressure builds up inside, the soul, like the magma, blows the top off the mountain…your body that is…and reveals the inside to the outside. That experience may have been new to you that night, but you’ve been carrying it around with you your entire life. It just finally made it out. You finally made it out.” And then, grinning once again, he said, “Welcome…to yourself!”

Shabbos Day

I THOUGHT ABOUT his words. “But why now?” I asked my chavrusa, “What triggered it all of a sudden?”

“I’m not sure,” he said. “Only you can really answer that question. Was there anything special that happened just before that?”

“Are you kidding?” I said. “I was so tired and just wanted to go to bed already.”

“That sure is spiritual,” he teased.

But as he did, something inside me caught my attention. I had asked the question to him, but seemed to be answering it myself, from the inside. I don’t even know what made me think of it, but once I did, it made sense to me. At the time of the incident, I had thought little of it, but I guess it left an impression on me, or rather, inside of me.

My wife and I had been guests for Shabbos lunch at our neighbor’s. It was Parashas Ki Savo, and the host, while talking about the curses found in the parsha, spoke about hester panim, the hiding of God’s face. He explained something that in all my years I had never heard, and used a moving story to make his point.

The story was about two brothers, and how the younger of the two liked to tag along with the older brother and his friends, especially on the day they decided to play hide-and-go-seek. The older brother would have said no, but their father insisted that the younger brother be allowed to join them.

As everyone ran to hide in one place or another, the younger brother did the same and waited to be found. But instead, his brother and friends used the opportunity to ditch the tag-along, who waited in vain to be found. When no one came looking for him for a long while and he could no longer hear any voices, he came out to investigate.

He didn’t understand at first what had happened, but it slowly dawned on him that while he had hidden, everyone else had left. Feeling abandoned, he began to cry and went home.

When he was close enough to his home, his father recognized his crying and came running out to see what had happened. The younger brother explained everything to his father in between his sobbing, after which his father began to cry as well. This distracted the son who then stopped crying as his father began to cry even harder.

Confused, the boy asked his father, “Abba, why are you crying? It happened to me, not to you!”

The tearful father said, “Because my son, until now I did not understand. You hid from the other boys, but not because you didn’t want to be found. You wanted the others to come looking for you, but was saddened when they didn’t. I realize now that the same can be said for God. He has hidden Himself, but not so we shouldn’t find Him, as many might think. But to see if care enough to go looking for Him…and yet so few do. How sad He must be!”

As the host finished his dvar Torah, my wife turned to look at me to see if I had enjoyed the analogy as much as she had, and was surprised to see a tear in my eye. What she did not know until later was that the story had happened to me with my older brother, several decades back. But my father had not heard me or come out to comfort me like in the story. Nevertheless, the story hit home and gave new meaning to an incident from my past. For a short while, I again felt the same pain, but this time I transferred it to God.

After all, my incident had experienced been an isolated incident, but it has been happening to God daily for thousands of years now. I was able to move on, but God has to deal with it every day. My brother and I eventually became the best of friends, but so much of mankind has turned its back on God. I found myself feeling very sad for Him.

We enjoyed the rest of seudah with our hosts and later returned home. The story, I had assumed, had simply become a memory.

Shalosh Seudot

WE ARE NOT always aware of the things that change us. Sometimes the subtlest of ideas can have the profoundest of impacts on a person, for good and unfortunately, for bad. Sometimes ideas can be planted as “seeds” in our minds, and take root and sprout on their own over time, changing us into better or, God forbid, worse people.

My neighbor may never know it, but his little story was such seed for good. It took a past sensitivity of mine that I had forgotten about and turned into one in the Present. But not for me this time, but for God. It enhanced my relationship with Him in a way I had not done before that.

What incredible hashgochah pratis—divine providence…that we were invited for a Shabbos seudah…the Shabbos of Parashas Ki Savo…which led to a dvar Torah with a story that seemed custom-designed for me. And it was amazing hashgochah that the first Selichos was later that night, while I was still impacted by the story. As a result, when I said Ashrei that Selichos night, I already felt a connection to God, and the sadness I had felt that afternoon once again moved me emotionally.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that it wasn’t just sadness I was feeling for God. It was also love, a more intense love. I mean, I had wanted to believe that I had always loved God, but the “sympathy” I felt for Him somehow made Him seem less far away…more accessible.

Or maybe it was the other way around. Maybe it made me less far away…more accessible. Until that day, I lived my Judaism from day to day, trying to be sincere but often falling short. Life can be very tiring and very distracting, especially when it comes to do mitzvos properly. I always knew God was there, you know, “there.”

My chavrusa thought that was really going on was that God had reached out to me. He thought that, once God saw me reach out to Him, He reached out to me. As the Gemora says, “Someone who comes to sanctify themself a little, they sanctify him a lot” (Yoma 38b). I told him that I really liked that idea.

The story, and the idea behind it made God seem more here to me, more a part of my everyday life. It talked to my soul and kind of neutralized my body in the process. The feeling of love just automatically resulted, and it spilled over into the way I learned, prayed, and did the rest of my mitzvos.

Who would have thought it? But then I began learning the next parsha, Nitzavim, and even that seemed to talk directly to me now. And all the promises that God made about bringing all of us back to Eretz Yisroel seemed so much more real, as if they were being made now. But the verse that really made me stop and think was this one:

And God, your God, will circumcise your heart and the heart of your offspring, [so that you may] love God your God with all your heart and with all your soul, for the sake of your life. (Devarim 30:6)

“Wow…” I said to myself softly, feeling all emotional again. I thought, “Did this not just happen to me?”

Though I had read that verse countless times before, it was always as if it was going to happen to some future generation, not mine. Not now. Now I felt blessed that it had happened to me, and wondered how many others it was happening to as well.