By HaRav Dov Begon

Rosh HaYeshiva, Machon Meir

The Prophet Isaiah (Chapter 4) addresses the prophets and sages in every generation and asks, “Comfort ye, comfort ye My people! Bid Jerusalem take heart” (verse 1). And what is the consolation Isaiah offers? “Proclaim unto her that her time of service is accomplished, that her guilt is paid off; that she hath received of the L-rd’s hand double for all her sins” (verse 2). In other words, the time earmarked for her in the exile has passed. The end of the exile has arrived, for she has received twice the punishment coming to her in the Babylonian exile and in the 2,000 year long exile. The atonement for her sin has been completed.

In the stage of actual redemption Isaiah addresses them and says: “O you who tell good tidings to Zion – get you up into the high mountain. O you who tell good tidings to Jerusalem – lift up our voice with strength. Lift it up! Be not afraid. Say unto the cities of Judah: ‘Behold your God! Behold, the L-rd G-d will come as a Mighty One” (verses 9-10). Those nations that will see fit to fight us will be like a drop in the bucket, like dust on a scale, as it says, “Behold, the nations are as a drop in the bucket, as the small dust of the balance. Behold the isles are as a mote in weight. Lebanon is not sufficient fuel, nor the beasts thereof sufficient for burnt-offerings. All the nations are as nothing before Him; they are accounted by Him as things of nought, and vanity” (verses 15-17).

Lebanon is here compared to a forest of trees all aflame. Isaiah addresses the skeptics, those weak in their faith, and he says: “Why do you say, O Jacob, and speak, O Israel: ‘My way is hidden from the L-rd; my right is passed over from my G-d’? Did you not know? Have you not heard that the everlasting G-d, the L-rd, Creator of the ends of the earth, faints not, nor is weary? His discernment is unfathomable. He gives power to the faint; and to him that has no might He increases strength. Even the youths shall faint and be weary, and the young men shall utterly fall. But they that wait for the L-rd shall renew their strength. They shall mount up with wings as eagles. They shall run, and not be weary; they shall walk, and not faint.” (27-31)

Today, with our own eyes we see Isaiah’s words being fulfilled in our day. After two thousand years of exile, after our having undergone the calamitous Holocaust, we are rising to rebirth in the land of our life’s blood. Millions of Jews are being gathered homeword, as Isaiah said, “Even as a shepherd who feeds his flock, who gathers the lambs into his arm, carrying them in his bosom, gently leading nurslings” (verse11). We can see with our own eyes how the land is developing with great strides. Roads and train tracks are being laid out, and the Isaiah’s words are being fulfilled: “‘Hark!’ one calls: ‘Clear in the wilderness the way of the L-rd, make plain in the desert a highway for our G-d.’ Every valley shall be lifted up, and every mountain and hill shall be made low; and the rugged shall be made level, and the rough places a plain” (verses 3-4).

The nations are rising up against us to fight us, and these nations are likened to grass: “The grass withers, the flower fades, because the breath of the L-rd blows upon it – Surely the people is grass. The grass withers, the flower fades; but the word of our G-d shall endure forever” (7-8). Looking forward to complete salvation,

Shabbat Shalom!

Friday, July 31, 2015

Hilarious Spoof Shows What Iran Thinks About the Nuclear Deal

This is a hilarious spoof video that pretends to show the (probably real) Iranian reaction to the nuclear deal that has been agreed to by the P5+1 powers, pointing out how ludicrous the deal actually is.

Although the translation in the video is false, the sentiment of the video and flaws it reveals are actually accurate. The nuclear deal with Iran is a terrible tragedy. Iran will receive between 500-700 billion dollars, which critics of the deal are certain will be used to fund even more terror around the world.

The nuclear deal also paves the way for Iran to acquire nuclear weapons within 10 years, even if they stick to the deal, which many feel is extremely unlikely. One has to wonder how much laughter there was behind closed doors in Iran, when the nuclear deal was actually signed.

Thursday, July 30, 2015

Moshe Feiglin: I Will Not Be at Ease Until I See Pollard in Israel

Former MK Feiglin, you are now in the US, but you did not see Pollard.

I have met with Jonathan Pollard 5 or 6 times in the past, but in the past 3 years, I have not seen him.

Tell me what transpired when you met him. Do you have a telephone connection with him?

No, that is much more complicated. Each meeting with him is in the presence of a representative of US Intelligence. The conversations must be carried out in English. Yes, until the last second, they treat him as some sort of ticking bomb who has ‘secret information’.

How were your meetings with Jonathan Pollard?

Meetings with him were always very emotional. He is an extraordinarily impressive person. He is very, very intelligent, focused, up-to- date; he knows exactly what is going on in Israel. He knows how to draw information from any person and put together a clear picture.

What are his sources of information?

The media that are open to him in prison, visitors and letters that he receives. He is very involved with what is happening in Israel. His courage, throughout the years, despite his burning desire to be released, is that he announced that he was not willing to be part of any terrorist release deal. He said that he understood what would happen in Israel if terrorists would be released. He is an almost indescribable idealist and a great lover of Israel.

Still? Despite everything? Despite the feeling of abandonment and anger, he still loves Israel?

Yes, you described it correctly. There are two feelings that exist simultaneously. On one hand, there is anger at the Israeli leadership throughout the years. It is not correct to say that Israel’s leadership abandoned him. The right word is ‘betrayed’ him. But on the other hand, a great love and feeling of responsibility for the Nation of Israel, which is amazing. A number of times, there were deals being put together for his release, and when it looked like terrorists were freed as part of the conditions for his release, he hurried to announce that he did not agree to be a playing card in the deal. He was completely aware of the significance of his stand, but was not willing to be a part of those deals.

Tell me, what did you think of his state of mind?

The first times that I visited him, I was amazed at his emotional strength. Later, I was concerned that perhaps he would not hold up. This is not up to date, because I have not visited him for over three years. But he is a strong man. I pray that he is still the same person that I knew.

Pollard is very, very sick. In my last discussions with his wife, Esther, she literally screamed in a live interview, “Do all that you can to get him released, because he will not survive.” What do you know about his health at this point?

He was already very sick when I met him the first time. I remember that he told me to apply pressure to his leg with my finger and it left a deep impression. He was very swollen. His health has suffered. The Americans have been very cruel to him. People think that America is a compassionate nation, but at least for the first half of his prison term, Jonathan was treated terribly. He did not see the light of day.

And what about the recent years?

In recent years he was transferred from a maximum security facility to a more moderate facility, and the situation has improved. It wasn’t a great improvement, but relative to his conditions before that, it was better.

Did he talk to you about the day that he would be released from prison?

He had all kinds of plans and suggestions for Israel. He thought up all kinds of inventions. He thinks of how to help the Nation of Israel and the State of Israel.

Apparently, Pollard will have to remain in the US for the next five years. What should Israel do to try to get him here earlier?

Israel has to finally start fighting for him. To tell you the truth, I am very apprehensive. I am not relaxed about this. We have been disappointed so many times when they told us that he is about to be released. Until I see him here – not there, out of jail – but here, I will not be at ease. We must understand that the President can veto the release at any given time. He may be released under confining conditions. They can come up with an excuse at any time to return him to prison. I will not be at ease until Jonathan is here in Israel.

Don't be afraid

By Rabbi Oury Cherki, Machon Meir

It would seem that the answer to this question can be found in the double encouragement of a verse later on:

"Climb up to a high mountain, herald of Zion, raise up your voice with strength, herald of Jerusalem. Lift it up, do not be afraid, tell the cities of Yehuda: Behold, here is your G-d." [40:9].

The prophet is teaching us that there are two items of good news – one by the herald of Zion, and one by the herald of Jerusalem.

The news of Zion, that is, Zionism, requires us to climb a mountain, in order to view history from a perspective that encompasses many generations. Only through an outlook that includes broad horizons is it possible to get a view of the hand of G-d guiding the events from behind the scenes. A superficial outlook, which involves paying attention only to immediate and pressing problems, is liable to generate despair in one's heart. The sages have taught us that the face of the generation of redemption is like the face of a dog. One interpretation of this statement is that when a person hits a dog with a stick it bites the stick and not the man holding it. This shows that it has a limited view, and in order to overcome this shortcoming the prophet tells us to climb a tall mountain.

The second news item, about Jerusalem, demands great strength, as in the verse, "He told His nation about the power of His deeds, to give them a heritage among the nations" [Tehillim 111:6]. The way to breathe a soul into the enterprise of redemption is to break out of normal limits of awareness, not only to see the hand of G-d but to develop a special brand of hearing, to be able to hear the voice of G-d (which Yeshayahu calls "your voice" – see above, 40:9). The voice of prophecy demands its rightful place in a world which has become accustomed through thousands of years of neglect to a situation where G-d's voice in no longer heard at all, and where it has been replaced by philosophy.

When the voice of G-d is not heard, moral bewilderment becomes the norm. Self-confidence disappears, and we suffer from a lack of strength, including the strength to fulfill the following command out of a feeling of moral righteousness: "I will pursue my enemies and I will reach them, and I will not return until they have been destroyed" [Tehillim 18:38]. Yeshayahu encourages us in our time of bewilderment. He calls out with all his might: "Raise up your voice with strength... Lift it up, do not be afraid, tell the cities of Yehuda: Behold, here is your G-d!"

The political strength of the nation illustrates the universalist viewpoint of Divine guidance: "Behold, the nations are like a drop in a bucket, and like dust rubbed off of a scale. The islands will be cast away like dust." [Yeshayahu 40:15].

And, from this exalted viewpoint, we are told to observe the greatness of the acts of creation: "Lift up your eyes and see – Who created these? He who brings out their hosts by number; He calls them by name. By the abundance of His power and by His vigorous strength, not one of them is missing."[40:26]. Behind the events of the hour, we are invited to meet the One who caused the world to be created by speaking, He who guides it from behind the misty curtains of international politics.

Rabbi of Beit Yehuda Congregation, Jerusalem

What is the meaning of the double consolation in the opening verse of the Haftarah, "Be consoled, be consoled, My nation" [Yeshayahu 40:1]? It is true that Zion "has been given double for all her sins" [40:2], and therefore it is due for double consolation. But what does this mean?

It would seem that the answer to this question can be found in the double encouragement of a verse later on:

"Climb up to a high mountain, herald of Zion, raise up your voice with strength, herald of Jerusalem. Lift it up, do not be afraid, tell the cities of Yehuda: Behold, here is your G-d." [40:9].

The prophet is teaching us that there are two items of good news – one by the herald of Zion, and one by the herald of Jerusalem.

The news of Zion, that is, Zionism, requires us to climb a mountain, in order to view history from a perspective that encompasses many generations. Only through an outlook that includes broad horizons is it possible to get a view of the hand of G-d guiding the events from behind the scenes. A superficial outlook, which involves paying attention only to immediate and pressing problems, is liable to generate despair in one's heart. The sages have taught us that the face of the generation of redemption is like the face of a dog. One interpretation of this statement is that when a person hits a dog with a stick it bites the stick and not the man holding it. This shows that it has a limited view, and in order to overcome this shortcoming the prophet tells us to climb a tall mountain.

The second news item, about Jerusalem, demands great strength, as in the verse, "He told His nation about the power of His deeds, to give them a heritage among the nations" [Tehillim 111:6]. The way to breathe a soul into the enterprise of redemption is to break out of normal limits of awareness, not only to see the hand of G-d but to develop a special brand of hearing, to be able to hear the voice of G-d (which Yeshayahu calls "your voice" – see above, 40:9). The voice of prophecy demands its rightful place in a world which has become accustomed through thousands of years of neglect to a situation where G-d's voice in no longer heard at all, and where it has been replaced by philosophy.

When the voice of G-d is not heard, moral bewilderment becomes the norm. Self-confidence disappears, and we suffer from a lack of strength, including the strength to fulfill the following command out of a feeling of moral righteousness: "I will pursue my enemies and I will reach them, and I will not return until they have been destroyed" [Tehillim 18:38]. Yeshayahu encourages us in our time of bewilderment. He calls out with all his might: "Raise up your voice with strength... Lift it up, do not be afraid, tell the cities of Yehuda: Behold, here is your G-d!"

The political strength of the nation illustrates the universalist viewpoint of Divine guidance: "Behold, the nations are like a drop in a bucket, and like dust rubbed off of a scale. The islands will be cast away like dust." [Yeshayahu 40:15].

And, from this exalted viewpoint, we are told to observe the greatness of the acts of creation: "Lift up your eyes and see – Who created these? He who brings out their hosts by number; He calls them by name. By the abundance of His power and by His vigorous strength, not one of them is missing."[40:26]. Behind the events of the hour, we are invited to meet the One who caused the world to be created by speaking, He who guides it from behind the misty curtains of international politics.

The Expulsion from Gush Katif: Looking Back from Within

By Rabbi Yisrael Rosen

Dean of the Zomet Institute

Exactly ten years ago on this date (in 2005), the expulsion from Gush Katif, the area of Azza, was completed. It began the day after the Ninth of Av, and it continued for a full week. On the day that I am writing this essay, this year's fast of the Ninth of Av, I returned to these dreadful events with a visit to the Katif Center (Museum) in Nitzan. (Whoever has not yet been there should make it his or her business to go!) The echoes of these days a decade ago are still blowing up in our faces to this day, and their effect can be felt within our nation and in the international arena to which the State of Israel belongs.

Looking Back

First I want to return to what I wrote in this column that year, and to bring back from the past three declarations from those days which engraved themselves in my heart and well up regularly within me. Looking at the dark pictures and films in the museum, I remembered what I wrote in my "Point of View" for Number 1081, Re'eih 5765: "Is it conceivable that Yisrael would destroy synagogues?" [Rashi, Devarim 12:4]. Sharon's government did decide to destroy both the synagogues and the Batei Midrash. The Supreme Court decided in favor of the rabbis, who claimed that never in our history had Jews destroyed their holy institutions in order to prevent our enemies from having this "satisfaction." And then I crowed like a bird in support of an alternative (for which I gave the credit to Yehuda Tzadok, of Petach Tikva): "Let the buildings be filled with concrete so that it will be virtually impossible to destroy them, and they will remain as eternal monuments for the minor Temples. I sent this proposal to the Sephardi Chief Rabbi, to the Chief Chaplain of the IDF, to the members of the relevant committee in the Chief Rabbinate, to other public figures, not to mention the press." Let it suffice for me to note that to this very day I have not received any reply, and the flames which reached towards the sky from these holy buildings were all photographed and filmed!

As time goes on, I have been asked more than once: What article is engraved most strongly in your heart from all those that you wrote throughout the years? My answer has always been what I wrote two weeks before the expulsion with the title, "Surrender, a White Flag, 'Rending Clothing,' and Exile" (Number 1076, Mattot 5765). I called out "with trembling fingers and a heart filled with blood that we should think about a status of surrender! The orange flag should be folded and replaced with a black flag flying at half mast, a white flag should be hoisted (not blue and white!). And we should go into exile, the way one goes to exile. We will be conquered by our own people, believers in the 'religion of democracy,' who were willing to betray their own faith in order to destroy the vision of those who cling to Eretz Yisrael! Democracy will blow up in their faces! The disengagement will blow up in their faces, when they discover that nothing has been accomplished!"

A Single Nation or Separate Tribes?

The question of whether I was right in the past is not important. The Zionist significance of these events appears in my article, "A Tear that is not Mended – Thoughts of Mourning" (Number 1080, Eikev 5765). In the article, I wrote a "divorce" to the Israeli left and called to "disengage" from it. "We are not brothers! When one part of the nation skewers the others on the sword of democracy, when the leader refuses to appear before those he expels and look them straight in the eye... when they refuse to discuss what we will gain from this brutality, when the political left is willing to overlook every conceivable kind of corruption to advance the 'holy objective,' when not a single one of these people finds it necessary to apologize to the pioneers of our generation – when this is a picture of the current situation, I cannot feel any brotherly love, at least not for the time being." Well, in past years, and especially very recently, some signs of regret by politicians and by military and police officials have appeared, but I am still waiting for an official statement of remorse from the Knesset and from the government of Israel. And the land will never be fully forgiven (see: Bamidbar 35:33) without the ultimate elements of repentance: Regret for the past and a resolution never to repeat the act in the future!

As time has gone by, I have been troubled by an additional "frightening" element, which I assume I have expressed in past articles: Eretz Yisrael has been abandoned by its nationalist-Zionist faithful, and it has been handed over almost exclusively to the religious sector, including its sons and daughters. My visit to the memorial center for Gush Katif strengthened this feeling. I fear that the public, both nationalistic and Zionist, which will be exposed retroactively to the expulsion, will be convinced that this was relevant to a specific sector of the nation, to a sub-sector, or at the most to a specific "tribe." It will be very difficult to convince the current and the next generation the truth in both Zionist and social terms – that many of the inhabitants of Gush Katif were farmers, "the salt of the earth," including many who were not religious at all, and not only highly emotional young religious people. And that the settlement in Katif was an initiative of the governments of Israel faithful to Mapai (Golda Meir, Yigal Alon, Yitzchak Rabin, and others) and not of bearded Gush Emunim fanatics or members of the Revisionist Party.

Have we Also been Expelled from the Hearts?

I am sorry to disappoint my readers, but it seems to me that the attempts to "settle in the hearts" of the people did not succeed, and the same is true of the "face-to-face" movement which tried to convince people to oppose the expulsion by visiting them in their homes all over the country. I know that in general every criticism should be accompanied by a suggestion for improving the situation, but I do not have any such proposal in this case. Perhaps something can be whispered in the ear of the Minister of Education, Naftali Bennett, who has a reputation as a person who knows how to meet challenges. The national educational institutions at all levels should be the proper arena for spreading the heritage of Gush Katif. This would mean such concepts as: (1) Settlement even in areas full of challenges and danger. (2) Clinging to land and eating by "the sweat of our brow" (see Bereishit 3:19). (3) The importance of social and cultural communities. And we must not forget: (4) Acceptance without violence any expulsion command, no matter how hallucinatory, together with (5) a legendary ability to brush off the dirt and to start all over again...

Dean of the Zomet Institute

Exactly ten years ago on this date (in 2005), the expulsion from Gush Katif, the area of Azza, was completed. It began the day after the Ninth of Av, and it continued for a full week. On the day that I am writing this essay, this year's fast of the Ninth of Av, I returned to these dreadful events with a visit to the Katif Center (Museum) in Nitzan. (Whoever has not yet been there should make it his or her business to go!) The echoes of these days a decade ago are still blowing up in our faces to this day, and their effect can be felt within our nation and in the international arena to which the State of Israel belongs.

Looking Back

First I want to return to what I wrote in this column that year, and to bring back from the past three declarations from those days which engraved themselves in my heart and well up regularly within me. Looking at the dark pictures and films in the museum, I remembered what I wrote in my "Point of View" for Number 1081, Re'eih 5765: "Is it conceivable that Yisrael would destroy synagogues?" [Rashi, Devarim 12:4]. Sharon's government did decide to destroy both the synagogues and the Batei Midrash. The Supreme Court decided in favor of the rabbis, who claimed that never in our history had Jews destroyed their holy institutions in order to prevent our enemies from having this "satisfaction." And then I crowed like a bird in support of an alternative (for which I gave the credit to Yehuda Tzadok, of Petach Tikva): "Let the buildings be filled with concrete so that it will be virtually impossible to destroy them, and they will remain as eternal monuments for the minor Temples. I sent this proposal to the Sephardi Chief Rabbi, to the Chief Chaplain of the IDF, to the members of the relevant committee in the Chief Rabbinate, to other public figures, not to mention the press." Let it suffice for me to note that to this very day I have not received any reply, and the flames which reached towards the sky from these holy buildings were all photographed and filmed!

As time goes on, I have been asked more than once: What article is engraved most strongly in your heart from all those that you wrote throughout the years? My answer has always been what I wrote two weeks before the expulsion with the title, "Surrender, a White Flag, 'Rending Clothing,' and Exile" (Number 1076, Mattot 5765). I called out "with trembling fingers and a heart filled with blood that we should think about a status of surrender! The orange flag should be folded and replaced with a black flag flying at half mast, a white flag should be hoisted (not blue and white!). And we should go into exile, the way one goes to exile. We will be conquered by our own people, believers in the 'religion of democracy,' who were willing to betray their own faith in order to destroy the vision of those who cling to Eretz Yisrael! Democracy will blow up in their faces! The disengagement will blow up in their faces, when they discover that nothing has been accomplished!"

A Single Nation or Separate Tribes?

The question of whether I was right in the past is not important. The Zionist significance of these events appears in my article, "A Tear that is not Mended – Thoughts of Mourning" (Number 1080, Eikev 5765). In the article, I wrote a "divorce" to the Israeli left and called to "disengage" from it. "We are not brothers! When one part of the nation skewers the others on the sword of democracy, when the leader refuses to appear before those he expels and look them straight in the eye... when they refuse to discuss what we will gain from this brutality, when the political left is willing to overlook every conceivable kind of corruption to advance the 'holy objective,' when not a single one of these people finds it necessary to apologize to the pioneers of our generation – when this is a picture of the current situation, I cannot feel any brotherly love, at least not for the time being." Well, in past years, and especially very recently, some signs of regret by politicians and by military and police officials have appeared, but I am still waiting for an official statement of remorse from the Knesset and from the government of Israel. And the land will never be fully forgiven (see: Bamidbar 35:33) without the ultimate elements of repentance: Regret for the past and a resolution never to repeat the act in the future!

As time has gone by, I have been troubled by an additional "frightening" element, which I assume I have expressed in past articles: Eretz Yisrael has been abandoned by its nationalist-Zionist faithful, and it has been handed over almost exclusively to the religious sector, including its sons and daughters. My visit to the memorial center for Gush Katif strengthened this feeling. I fear that the public, both nationalistic and Zionist, which will be exposed retroactively to the expulsion, will be convinced that this was relevant to a specific sector of the nation, to a sub-sector, or at the most to a specific "tribe." It will be very difficult to convince the current and the next generation the truth in both Zionist and social terms – that many of the inhabitants of Gush Katif were farmers, "the salt of the earth," including many who were not religious at all, and not only highly emotional young religious people. And that the settlement in Katif was an initiative of the governments of Israel faithful to Mapai (Golda Meir, Yigal Alon, Yitzchak Rabin, and others) and not of bearded Gush Emunim fanatics or members of the Revisionist Party.

Have we Also been Expelled from the Hearts?

I am sorry to disappoint my readers, but it seems to me that the attempts to "settle in the hearts" of the people did not succeed, and the same is true of the "face-to-face" movement which tried to convince people to oppose the expulsion by visiting them in their homes all over the country. I know that in general every criticism should be accompanied by a suggestion for improving the situation, but I do not have any such proposal in this case. Perhaps something can be whispered in the ear of the Minister of Education, Naftali Bennett, who has a reputation as a person who knows how to meet challenges. The national educational institutions at all levels should be the proper arena for spreading the heritage of Gush Katif. This would mean such concepts as: (1) Settlement even in areas full of challenges and danger. (2) Clinging to land and eating by "the sweat of our brow" (see Bereishit 3:19). (3) The importance of social and cultural communities. And we must not forget: (4) Acceptance without violence any expulsion command, no matter how hallucinatory, together with (5) a legendary ability to brush off the dirt and to start all over again...

Who’s Afraid of the Temple? Everyone

By Moshe Feiglin

The secular have been brainwashed to believe that the Temple – the source of world peace and stability – will create a world war. The religious think – rightfully – that the Temple will destroy their religion. In other words, the Temple will extricate Judaism from its narrow, religious, detached-from-reality framework and restore it to its original, all-encompassing stature. Judaism will then be part of every facet of life, from the most mundane and personal to the most sublime and universal. The religious are not enthusiastic about that. The Zionist Jews have become used to the separation between holy and mundane (the complete opposite of their declared ideology) and the ultra-Orthodox have become used to being detached from the mundane. Everybody is quite comfortable in their own shallow and murky ponds.

The Temple threatens everybody’s world. It sanctifies everything. And due to the fears of the observant Jews, it still lies in destruction. Only because of the fears of the observant Jews.

In a visit some time ago to the Temple Mount, we met some of the paratroopers who had liberated Jerusalem in the Six Day War. “It looks like you will have to re-capture the Temple Mount,” I said to one of them. “We’re ready and waiting for orders,” the aging veteran answered with a smile.

With G-d’s help, we will soon have authentic Jewish leadership that will issue those orders.

Illustration courtesy of The Temple Institute

The Historical Beginning of Anti-Semitism: HaRav Nachman Kahana on Parashat Va’etchanan 5775

| |||

|

Tuesday, July 28, 2015

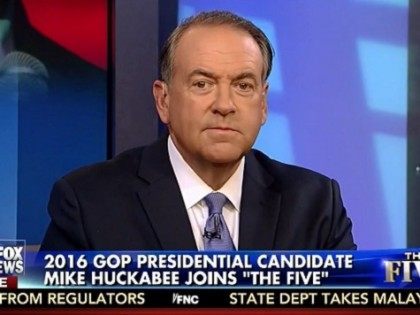

Huckabee: Why Wouldn’t I Bring Up the Holocaust When ‘We’re on the Verge of Repeating It’?

From Breitbart News. Video also available at the site.

by IAN HANCHETT

Republican presidential candidate and former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee defended his remarks about the Iran deal, stating “we’re on the verge of repeating it [the Holocaust] again with a nation that is threatening to do that very thing,” so it makes no sense to avoid bringing up the Holocaust on Monday’s broadcast of the Fox News Channel’s “The Five.”

When asked if he stood by his comments, Huckabee stated, “Absolutely I do. Absolutely I do. The last time the world did not take seriously threats that someone was going to kill massive amounts of Jews, we ended up seeing 6 million Jews murdered. We didn’t take it seriously. The Iranian government — we’re not talking about a blogger here, we’re talking about the Iranian government — has repeatedly said that it’s going to be easier to take the Jews out because they’re all concentrated in Israel, we won’t have to go all over the world and hunt them. They used the word ‘holocaust.’ They used that word in talking about what they wanted to do. They refused, in this negotiation, to recognize Israel’s right to exist. They refused to tone down their rhetoric and continued to say that the Holocaust did not exist, and that they’re going to wipe Israel off the face of the map. When people who are in a government position continue to say they’re going to kill you, I think somebody ought to wake up and take that seriously.”

Co-host Dana Perino then argued, “he [Obama] has said repeatedly anybody who is against the deal that he is making with Iran, that they are warmongers, they just want war, which is unfair and unserious. But I do think that, from a rhetoric standpoint, when you bring up the Holocaust, everybody loses.” And “I that think that for Democrats who are on the fence, of possibly refusing to go along with Obama on this deal, that then, all of a sudden, they get pushed into a position of defending the president. And you even saw Joe Manchin today of West Virginia say he’s probably going to support the deal.”

Huckabee responded, “Well, if I get credit for them supporting the deal, then I’m a much, much bigger deal than I think people thought I was. Look, here’s what I would want to remind people: If we don’t take seriously the threats of Iran, then God help us all, because the last time — it’s Neville Chamberlain all over again. We’re going to just trust that everyone’s going to do the right thing. Three times I’ve been to Auschwitz, when I talked about the oven door, I have stood at that oven door. I know exactly what it looks like. 1.1 million people killed. For 6,000 years, Jews have been chased, and hunted, and killed all over this earth, and when someone in a government says, ‘We’re going to kill them,’ I think, by gosh, we better take that seriously. And for the president to act like that the only two options are have a war or take his deal, that got nothing, got nothing. We didn’t get the hostages out. We didn’t didn’t get a concession that they would stop this rhetoric about wanting to wipe Israel out, or they didn’t stop chanting ‘Death to America.’ We got nothing. I read the whole thing, I read it, and I thought you’re kidding. This is it? This is the best deal? Why can’t we criticize it?”

Co-host Geraldo Rivera then stated that as a Jew, he thinks Huckabee’s comments were “inappropriate.” And “There are some place you cannot go. You cannot compare the slaughter of 6 million Jews to anything, other than, maybe the slaughter of the Armenians or something else in history. You cannot compare it to a negotiation over a deal like this.”

Huckabee asked in response, “Why do we have the Holocaust Museum in Washington? Why do we have Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, that I visited dozens and dozens of times? Why do we have it?” Rivera answered that those things are “sacred” and shouldn’t be politicized. He added, after Huckabee asked again “to remember.”

Huckabee continued, “Why? So that we never repeat it again. If we’re on the verge of repeating it again with a nation that is threatening to do that very thing, how do we not bring up that language?”

Geraldo responded, “We don’t even use that when there’s a slaying in a school, and multiple victims. We still don’t go there. Because this was the systematic attempt by an industrialized nation to wipe out a race of people. That is different. That is unique. You may not go there. And I’m begging you to apologize and to retract that.”

Huckabee declared, “I will not apologize and I will not recant, because the word ‘holocaust’ was invoked by the Iranian government. They used that very word.” Geraldo answered by asking, “Are we going to go there then?” And pointed to the Anti-Defamation League’s condemnation of Huckabee’s remarks

Huckabee responded by stating, “the Democrat Jewish community’s been universal in condemning it. For them, it is a political issue. For me, it is not. It’s a humanitarian issue. And when you have a government saying they’re going to kill every Jew on the planet earth, and they use the term ‘holocaust,’ I’m not sure why we have memorials about the Holocaust if we’re not going to remember why we had it, what happened to 6 million Jews, how they were systematically murdered. And the fact is Geraldo, that’s exactly what the Iranians have said for, I mean, as long as the ayatollahs have been in power, for 36 years. They have continually said, ‘We’re going to kill every Jew.’ Now, at what point when a gun is pointed to your head do you not take that seriously?”

Co-host Eric Bolling said he doesn’t take issue with the comment itself, but rather, “My problem is that it took the focus away from what President Obama said, that 99% of the world is in agreement with this deal, which I fully, fully disagree with, number one, and number two, who cares about the rest of the world? I care about what Americans think. And right now, I think there’s 50% of Americans who hate this deal right now. And can we just focus on that for a little bit? Can you answer President Obama’s comment that 99% of the world is in agreement with the deal?”

Huckabee addressed Obama’s comment by wondering why “none of the people in that neighborhood” supported the deal if it is was such a great deal. He also pointed to Israel’s opposition to the deal, which he argued was possibly “because they, too, have seen this movie before, and they know that it does not end well. I think it’s a naive deal, and it didn’t get anything. I mean, you should have had some preconditions. The precondition should have been three things, at least: Four hostages…should have been released. They should have been on the next plane home. You should have had a concession that no more anti-/death to America talk, and no more talk about wiping Jews off the face of the earth and destroying Israel.”

Co-host Tom Shillue defended Huckabee’s remarks, which he argued is “a sober statement to make, because when they announced the deal they were saying, ‘Death to America, death to Israel.’ So, it makes perfect sense to me.”

Sunday, July 26, 2015

Israel's technology protects British troops in Afghanistan

By Ambassador (ret.) Yoram Ettinger

1. "British Prime Minister David Cameron: 'Israel's technology is protecting British and NATO troops in Afghanistan….' UK-Israeli trade is at an all-time high, despite recent rumblings by the EU over the labelling of products from the West Bank and calls in some quarters for a boycott of Israeli goods….HSBC, Barclays, Rolls-Royce, GlaxoSmithKline and Unilever have a major presence in Israel. One out of every seven prescriptions filled by Britain's National Health Service is from an Israeli pharmaceutical firm…. There are raft of government initiatives to propagate growth spearheaded by a recent trip to Israel, by Prime Minister David Cameron, as well as favorable tax treaties…. Britain's trade with Israel reached a record high of £5.1billion last year after doubling during the last decade. The UK is Israel's second largest trading partner after the US.... More firms listed in London's stock exchange last year from Israel than from anywhere in the world, other than the UK itself…. Technology from Israel is used by a host of British firms, from cyber security used to protect High Street cash machines to chips that go in TV set-top boxes."

2. $835mn raised by Israeli companies, on the British Stock Exchange, during the first seven months of 2015 (Globes Business Daily, July 13, 2015).

3. Steve Forbes, July 22, 2015: "Israel is now one of the top two or three high-tech powers in the world–ahead of the European Union, with its 500 million people.…"

4. The following Israeli companies were acquired during the first 7 months of 2015: Lumenis acquired by XIO Private Equity for $510mn, Cliquesoftware by San Francisco Partners - $438mn, Annapurna Labs by Amazon - $360mn, Adallom by Microsoft - $320mn, Red Bend by Harman - $200mn, Panaya by InfoSys - $200mn, Exelate by Nielsen - $200mn, CloudOn by Dropbox - $100mn, WatchDox by Blackberry - $100mn, Spectronics by Emerson Electric - $100mn, Stockton Agrochemicals by China's Sichuan Hebang Corp - $90mn,Equivio by Microsoft - $75mn, Discretix by ARM - $75mn, OrAd hightech by Avid Technologie - $70mn, Intellinx by BottomLine - $67mn, CyActive by PayPal - $60mn, Matan Printing by EFI - $50mn, Deeprz by Como - $50mn, ARX by DocuSign - $40mn, Kima Labs by GroupOn - $35mn, AppsFire by Mobile network Group - $30mn, Appoxee by TeraData - $25mn, LinX by Apple - $$20mn, IdmLogic by Computers Associates (CA) - $20mn, Porticor Cloud Security by Intuit, Ntrig by Microsoft, Quantum Materials Company by Merck, and ConteXtream by HP – each for a few scores of million dollars (Globes, July 21).

5. Israel's NeuroDerm and Chiasma raised $170mn on NASDAQ (Globes, July 17). $84mn invested by Insight Venture Partners in Israel's cyber company, CheckMarx (Globes, June 26).

6. $5.3bn during the first six months of 2015 is the total acquisitions of Israeli companies, Israeli IPOs and joint ventures – 76% of the total during the entire 2014, $6/9bn and 80% of 2013, $6.6bn (Globes, July 8).

7. The London Economist, July 18, 2015: "Israel is pivoting to Asia…. India is buying $7bn of Israeli military systems…. Dozens of Chinese businessmen and officials from all levels of government visit Israel each month. In 2014, Chinese companies invested nearly $4bn in Israel….The Director of Shengjing, Beeijing-based consulting firm, which facilitates Chinese investments in Israeli technologies, visited Israel 15 times in the past two years…."

Oren’s “Ally”

Last week, a Muslim Arab named Abdul Azeez shot and murdered five US soldiers at military recruiting centers in Tennessee on the last day of Ramadan, and the Obama administration, puzzled, will not leap to conclusions about the motive of the attacker. Of course, a ten year-child with a casual familiarity with the news could tell us what the motive was, and so the officials responsible for protecting the American people must be seeking some motive “other” than the obvious.

This ongoing flight from reality – and the dramatic changes that have been wrought to American foreign policy in the last six years – is the subtext of Michael Oren’s “Ally: My Journey Across the American-Israeli Divide.” For those who wish to know the inside story of the deterioration of relations between the two countries since Obama became president – a willful and intentional distancing from and disrespecting of Israel and the traditional alliance and friendship between the two countries, it is a fascinating, and at times, riveting read. Oren, a New Jersey native who was Israel’s ambassador to the United States for four years of the Obama presidency, had a front row seat to the tumultuous twists and turns, and as an historian, a keen eye for both small details and the big picture.

Oren’s portrait of the life of an ambassador, at least Israel’s ambassador, is wearying in the best sense of the word. There were times when I felt tired just reading about his day. The early morning calls to and from Israel, the rowing on the Potomac for some private time, and then the lobbying, speeches, travel, embassy management, daily crises and endless cocktail parties late into the night followed by more calls to Israel, are enough to drive anyone to drink, which seems to be what people do at the nightly cocktail parties anyway. His personal story is compelling, notwithstanding the gaps in his narrative. A young oleh who becomes a lone soldier and within a relatively short time finds himself on official business in the Soviet Union and then sitting as an advisor to the Israeli mission at the UN was apparently more than an IDF paratrooper but likely involved in some clandestine work as well. His access to high government officials, long before his official posting to Washington, is unusual by the standards of the average American oleh, and his rise – which took decades – nevertheless seems meteoric. He can be excused those gaps.

By all accounts, he is immensely talented and articulate, and as a reader of both of his prior history books, I have learned that he is a perceptive historian and keen analyst. Reviews of “Ally” have extracted the sound bites, the inside baseball of who like and dislikes whom, and confirmation or refutation of certain events that were rumored to be true. Oren does rebuff some of the conventional wisdom of the last few years: in one celebrated incident, Obama allegedly dissed Netanyahu by leaving him to eat dinner with Michelle and children, disappearing for hours and leaving Netanyahu to stew in the White House alone. Oren debunks that, claiming that Michelle and the girls were not even in the White House that night and Obama merely said he was going to sleep (at 9:00 PM) and the rest of the team of Israelis and Americans worked for several hours. Of course, Oren is also reporting just what he was told and saw, and it is unclear why the sleep excuse was better than the dinner excuse – but nothing can hide the unprecedented animosity between the leaders of the two countries. Much of Oren’s work as ambassador seemed to be defusing explosives and smoothing over rough spots in the relationship. He failed, but only because the experiences, world views, value system and interests of Netanyahu and Obama are so incompatible.

Leaving aside the commonly reported anecdotes, a few points struck me about Oren’s experiences. The book focuses on the tug of war between the two identities Oren bears within him – as an American and as an Israeli, no more poignantly reported than in the book’s opening when Oren had to surrender his US passport and renounce his American citizenship at the US embassy in Tel Aviv before assuming his post in Washington. It is quite moving and the range of emotions – and tears – palpable. (His wife and children retained their US citizenship.) Yet, it is equally clear that Oren retains strong and mostly positive feelings about America, which is welcome, if only in that it sets him apart from other American olim who feel some compulsion to appear more Israeli by disparaging the land of their birth.

With that, Oren is not a typical American oleh in that he is a mostly secular Jew with a strong sense of Jewish identity. He tends to regard the religious component of Judaism (that is to say, its essence) as just one (oftentimes lamentable) aspect of the kaleidoscope of pluralism that he cherishes, and so the Orthodox, their lifestyle, the obligation ofmitzvot, and even the settlement of the land of Israel are perceived more as inconveniences than they are desiderata. The cultural and national facets of Judaism animate him more than the religious, which dovetails with his upbringing, but leaves him grasping to find cogent reasons why the modern Jewish people has any claim to the land of Israel more substantive than that our forefathers once lived there.

As such, he did and does find the settlement movement to be an irritant, and if he doesn’t fully subscribe to the execrable theory that but for the settlements there would be peace, he doesn’t firmly repudiate it even if he acknowledges that they too are Israelis whose views must be considered. Similarly, he clings to the two-state solution fantasy, even if (better than the political left) he realizes that the time is not yet ripe and might never be ripe for another partition of the land of Israel. Like others of his background and temperament, he yearns for the halcyon days of Ben-Gurion, which in reality were not so peaceful but during which Israel’s international reputation was much more favorable, cushioned as it was by the detritus of the Holocaust.

Yet, Oren is also acutely aware of the unique role he was given. Secular Israelis are always a little suspicious of Americans who make aliya (who leaves a land with everything for a land of milk and honey?) and continue to perceive them as Americans. To Israelis, he remained Michael (not Mee-kha-el) and I was curious – he doesn’t say – whether Netanyahu generally conversed with him in Hebrew or in English. (He often drafted Netanyahu’s English remarks but Netanyahu also wrote his own or deviated from the text with the soaring oratory to which we have become accustomed.) Indeed, Oren’s appointment followed a Netanyahu pattern in his second tenure as Prime Minister, in selecting for prominent positions a non-rightist (Oren, Livni, Barak) so as to buy protection from a hostile media and a potentially adversarial US administration. It didn’t always work, although in fairness, it might have been (and be) worse without that moderate cover.

Read from a broad perspective, the book can be used to answer one bewildering question: if Iran is the enemy of the United States and Israel, and Israel and the US are allies, then why is the United States strengthening its enemy Iran while weakening its ally Israel?

The answer will trouble Obama’s Jews who also claim to love and support Israel. Obama has endeavored to undermine the relationship between the two countries from the very beginning of his term. It is well known that Obama sought to create daylight between the diplomatic positions of the two countries from the moment he took office, in two ways. The first was by demanding a settlement freeze, followed by an Israeli surrender of territory and the creation of a Palestinian state. Netanyahu was resistant, although he did weaken several times – conceding the establishment of an Arab state in his Bar Ilan speech or acceding to a ten month settlement freeze in order to induce Mahmoud Abbas to negotiations. Both were coerced by an Obama administration that has never tired in its demands for shows of good faith by Israel and only Israel, and neither worked, for reasons much discussed in recent years. More importantly, notwithstanding all these concessions, Netanyahu was still blamed for the absence of peace; Abbas? Never .Indeed, Oren – like others – concludes that Obama’s hostility to Israel made Abbas’ positions even more hard-line than they otherwise would have been.

The second way that Obama has impaired the US-Israeli relationship is by reorienting US foreign policy away from support for Israel (and even pro-American Sunni Muslim countries like Jordan, Egypt and Saudi Arabia) and towards Iran, as bizarre as that sounds. I can’t help thinking that the hand of Iranian-born Valerie Jarrett is behind this, but do not exclude Obama’s own radical ties as he ascended the political ladder in Chicago. Oren maintains that the key to Obama still lies in the two autobiographies he wrote, in which his radical views are delineated, but too little attention was paid to them.

Thus – in an exchange that is especially prescient these days – Oren in conversation with Henry Kissinger was incredulous that the US would allow Iran to become a nuclear power and thereby end American hegemony in the Middle East. Kissinger: “And what makes you think anybody in the White House still cares about American hegemony in the Middle East?” Indeed, and it is therefore not surprising that Obama could acquiesce in Iran’s nuclear program even as Iranian leaders and mobs shout “Death to America!”

There is something ominous in Oren’s behind-the-scenes political accounts, some of which have recently precipitated White House calls for apologies and corrections for the airing of unpleasant truths, and that is this: Obama has tried to shield himself from accusations of being anti-Israel not only by doing the obvious nice (helping extinguish the Carmel fire) and the political nice (supporting Israel at the UN) but also by surrounding himself with Jews (Emanuel, Axelrod et al) and using them as his attack dogs against Israel. In fact, the only Democratic politician who publicly stood up to Obama was the disgraced Congressman Anthony Wiener, an odd duck for several reasons including his marriage to an Arab Muslim who is a leading advisor to Hillary Clinton, a public friend of Israel but in private, as Secretary of State, as nasty to Israelis as any Obama-ite.

This fear of defying Obama – and it is a fear – will weigh heavily on Democratic and especially Jewish Democratic Congressmen in the upcoming deliberations over the Bad Deal with Iran. (It’s very American; we have had the New Deal, the Fair Deal, the Square Deal and now we have the Bad Deal.) Chuck Schumer is in an unenviable position only because he is a politician. He yearns to succeed Harry Reid as Senate Democratic leader –and if he opposes Obama on Iran, it is extremely unlikely even though Obama will be gone from office. Democrats will come under intense pressure, and for supporters of Israel and a strong America, it is not enough to vote no. They have to solicit other “no” votes as well. Democrats are forced into bitter struggle between the right choice and the expedient choice.

There was also an astonishing level of personal animosity towards Israel and its elected leaders that was apparent in many ways. One stood out: in autumn 2012, Netanyahu planned a military strike against several of Iran’s nuclear facilities. He was threatened by administration officials with dire consequences if he attacked. He didn’t. A year later, those same officials ridiculed him as a coward using a common barnyard epithet. And the White House routinely publicized proposed Israeli attack mechanisms to warn Iran and remove the element of surprise. This is the Obama for whom 7 of 10 Jews voted.

It is also distressing, albeit commonplace, to recognize the politician’s knack for the redundant repetition of code words that mean little and are often utter falsehoods. Oren almost laughs recalling the incessant references of the Obama team to the US-Israeli alliance as “unbreakable and unshakeable.” Even as the administration was trying to break it and shake it, liberal Jews still loved to hear the words, which matter to them more than actual deeds. Oren doesn’t say it, but that phrase could take its place with “if you like your doctor, you can keep your doctor,” “Iran will never be allowed to obtain a nuclear weapon” and “in case of violations, sanctions will snap back.”

Additionally, while on the topic of words, Oren notes that there is no greater dichotomy than the politician’s suave, dignified posture in public and the rampant vulgarity and crudity that take place off-stage.

But with all the turbulence in recent years, there still is a pervasive sense that the US-Israeli relationship is unbreakable and unshakeable, transcends even the hostility of any particular president, and can really “snap back” given effective and sympathetic leadership in the future. That is because, as Oren underscores eloquently, the intrinsic values of both countries are similar, rooted as they are (at least fundamentally) in the Torah and shared notions of human rights, personal freedom and universal morality. In that sense even the term “ally” is limiting. I once heard President Bush (II) emphasize that the Saudis are allies but the Israelis are friends – and friends share a closer bond than allies.

Oren’s Ally is a well written, engaging book, filled with trenchant analysis that clearly articulates a widely held view in Israel. Mistakes do creep in to any book and here as well. Omri Casspi plays “in”

the NBA, not “for” the NBA, and more egregiously, Senator Joe Lieberman was a candidate for Vice-President in 2000, not 2004. But even as one can take issue with certain policy conclusions and even some of his world views, Michael Oren – a dedicated servant of the Jewish people, now a Member of Knesset from Kulanu – has written a book that gives us an enthralling inside view of all the complications, complexities and vicissitudes of the relationship between the United States and Israel, a relationship that is bound to get more prickly in the coming months. For sure, the nature of that alliance will be a critical issue during the coming presidential campaign assuming that Jews finally wake up and cease casting their political fortunes with just one party, indeed, the party that is actively engaged in enabling Israel’s most implacable foe to acquire the deadliest weapons known to man.

the NBA, not “for” the NBA, and more egregiously, Senator Joe Lieberman was a candidate for Vice-President in 2000, not 2004. But even as one can take issue with certain policy conclusions and even some of his world views, Michael Oren – a dedicated servant of the Jewish people, now a Member of Knesset from Kulanu – has written a book that gives us an enthralling inside view of all the complications, complexities and vicissitudes of the relationship between the United States and Israel, a relationship that is bound to get more prickly in the coming months. For sure, the nature of that alliance will be a critical issue during the coming presidential campaign assuming that Jews finally wake up and cease casting their political fortunes with just one party, indeed, the party that is actively engaged in enabling Israel’s most implacable foe to acquire the deadliest weapons known to man.

More importantly, on a personal level, Oren’s tale is captivating – the New Jersey kid who dreams of becoming Israel’s ambassador to the United States and fulfills that dream, after making aliya alone. It is the dream of every oleh – to settle in and make a positive contribution to society – and thus both an American and an Israeli success story.

HUCKABEE: OBAMA MARCHING ISRAELIS TO ‘DOOR OF OVEN’

Theo Stroomer/Getty Images

by ROBERT WILDE

Presidential aspirant and former governor of Arkansas Mike Huckabee joined Breitbart’s editor-in-chief Alexander Marlow in an interview on Saturday.

Appearing on Breitbart News Saturday, the governor demonstrated his keen ability to articulate conservative principles and values—a likely reason why he enjoys the highest favorability ratings of all GOP candidates running for president in 2016.

Governor Huckabee didn’t pull any punches when talking about Obama’s Iran nuclear deal: “This president’s foreign policy is the most feckless in American history. It is so naive that he would trust the Iranians. By doing so, he will take the Israelis and march them to the door of the oven. This is the most idiotic thing, this Iran deal. It should be rejected by both Democrats and Republicans in Congress and by the American people. I read the whole deal. We gave away the whole store. It’s got to be stopped.”

Modestly, Huckabee acknowledges that his high favorability rating is good news. “People don’t vote for someone they don’t like. So I just got a make sure I don’t start doing stuff that make people stop liking me,” he chuckled.

Marlow, who hosts the program airing on Sirius XM Patriot radio channel 125 on Saturday mornings, asked Huckabee, “What are conservatives fighting for in this race?”

Huckabee answered that he believes the biggest mistake conservatives make is they speak like they are talking “to an assemblage of people in the corporate board room on Wall Street.” Instead, he explained that conservatives need to convey a simple message of “conservatism, limited government, more local government, lower taxes, and less regulation to people who sweat through their clothes everyday and have to lift heavy things to make a living.”

Huckabee added that when “We fail to communicate to working men and women of this country, they don’t connect with us. Ineveitably we lose.”

Marlow asked the governor what is his concept of American values. Huckabee replied that American values can be summed up in the language of the Declaration of Independence. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, all of us are created equal, we are endowed by our Creator with certain unalienable rights: life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

To the governor, our values boil down to everybody plays by the same rules in America. “We are a nation of law—not emotions, not men, not money, not power—but a nation of law,” he clarified. “Our worth and our value comes from a higher source, God. Not the government, but from God.” Huckabee informed that from this fundamental value all other values emanate.

Marlow changed the topic to the ongoing Planned Parenthood scandal. He asked the governor what he thinks about the American government funding the largest abortion provider in the nation, recently exposed for allegedly selling baby body parts and fetal tissue.

The 59-year-old author and former Fox News host said that he has formally called for the immediate end to government funding of Planned Parenthood. Unfortunately that may be difficult. Huckabee pointed out that “Democrats get a lot of money from the pro-abortionists.”

The amenable statesman recounted that he has called for the defunding of Planned Parenthood for years. “The fact that they are getting between $500-540 million of taxpayer money is really a disgrace,” he asserted. “It is disgusting to fund an organization like Planned Parenthood that chops up babies and sells the parts like parts to a Buick.”

America needs to “come to grips with a 42-year nightmare of taking babies from their mother’s womb. This needs to come to an end,” insists Huckabee.

The country needs to be “civilized,” Huckabee contends. He told Breitbart News Saturdaylisteners that if he were president, it would be his job to make sure the government was protecting innocent human life, not destroying it and selling it for a profit.

When asked by Breitbart’s EIC how he would handle massive illegal immigration, the governor responded that the first thing he would do is seal the border. He compared the crisis to a broken pipe in your kitchen. “When water is everywhere, the first thing you have to do is stop the leak.”

The governor said that a major part of the illegal immigration problem is “Big Business makes sure that nothing ever gets done.” He argued that the best way to take away advantages of being an illegal immigrant is to institute a consumption tax. The illegals and the cartel drug dealers don’t pay the kind of taxes that most working Americans have to pay.

“They don’t report their income and the employer’s are not paying the employer tax,” Huckabee complained. “If you take away this financial advantage, you are going to see Americans going back to work.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)