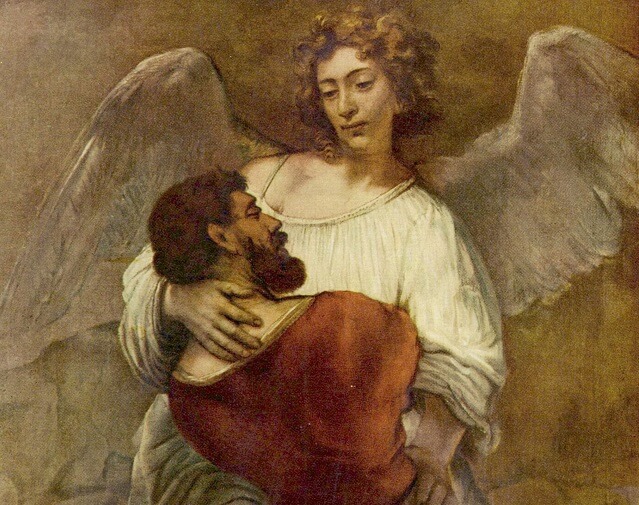

The prophet of Israel, describing what can unfortunately be characterized as the usual situation in Jewish life, states that it is comparable to one who flees from the lion and finds one's self in the embrace of a bear. Our father Yaakov, who barely escapes from the treachery of Lavan, soon finds himself confronted by the deadly mob of his brother Eisav.

Yaakov, in his confrontation with Lavan, chooses the option of flight as he removes himself from the territory controlled by Lavan and his sons. But this option of flight is no longer possible in his contest with Eisav. Jacob is in his own land, the land of his ancestors, the land promised to him personally by God Himself, to be his rightful residence. As such, Yaakov has nowhere to run.

As taught to us by Midrash and quoted by Rashi, his only options were to stand and fight, to buy Eisav off with monetary tribute, and/or to pray. The option of fleeing does not enter the equation in any fashion. This is perhaps the basis for the well-known Talmudic dictum severely limiting the right of a Jew to leave the Land of Israel cavalierly.

Polish Jewish history, from biblical times to the present, shows us that exile from the Land of Israel on a collective basis never occurred voluntarily. The most mobile, wandering people in the history of civilization never left their homeland of their own volition. In this they were following the example of their father Jacob, who never considered fleeing from the Land of Israel in order to avoid the long expected and dreaded confrontation with his aggressive and volatile brother.

In our long and winding road of exile, over the past two millennia, when one country closed down for us because of economic, social or religious reasons, the Jewish people moved on elsewhere. But as we have discovered, we have run out of places to go in the world. There are no new undiscovered continents on the face of the globe, no seemingly safe havens left for escape.

This is part of the reason for the establishment of the State of Israel and its phenomenal growth and inexplicable stability. Even though it has been provoked by errors of policy and with concessions to its neighbors, it is as though the Jewish people, like their ancestor Yaakov, declared that this is where they will make their stand.

Prayer is a constant in current Israeli life, even for those who do not deem themselves to be observant of Jewish law and tradition. But in spite of all of the troubles, problems, and the myriad challenges that living in our country poses, flight in a collective sense is a nonexistent possibility.

Unable to defeat us militarily or economically, even though diplomatically they have wounded us severely, our enemies openly declare their intent to make us leave our homeland. But that is a very unrealistic policy. The children of Yaakov, in the state that bears his name, certainly will follow his example until it finally brings quieter times and better relations.

Yaakov, in his confrontation with Lavan, chooses the option of flight as he removes himself from the territory controlled by Lavan and his sons. But this option of flight is no longer possible in his contest with Eisav. Jacob is in his own land, the land of his ancestors, the land promised to him personally by God Himself, to be his rightful residence. As such, Yaakov has nowhere to run.

As taught to us by Midrash and quoted by Rashi, his only options were to stand and fight, to buy Eisav off with monetary tribute, and/or to pray. The option of fleeing does not enter the equation in any fashion. This is perhaps the basis for the well-known Talmudic dictum severely limiting the right of a Jew to leave the Land of Israel cavalierly.

Polish Jewish history, from biblical times to the present, shows us that exile from the Land of Israel on a collective basis never occurred voluntarily. The most mobile, wandering people in the history of civilization never left their homeland of their own volition. In this they were following the example of their father Jacob, who never considered fleeing from the Land of Israel in order to avoid the long expected and dreaded confrontation with his aggressive and volatile brother.

In our long and winding road of exile, over the past two millennia, when one country closed down for us because of economic, social or religious reasons, the Jewish people moved on elsewhere. But as we have discovered, we have run out of places to go in the world. There are no new undiscovered continents on the face of the globe, no seemingly safe havens left for escape.

This is part of the reason for the establishment of the State of Israel and its phenomenal growth and inexplicable stability. Even though it has been provoked by errors of policy and with concessions to its neighbors, it is as though the Jewish people, like their ancestor Yaakov, declared that this is where they will make their stand.

Prayer is a constant in current Israeli life, even for those who do not deem themselves to be observant of Jewish law and tradition. But in spite of all of the troubles, problems, and the myriad challenges that living in our country poses, flight in a collective sense is a nonexistent possibility.

Unable to defeat us militarily or economically, even though diplomatically they have wounded us severely, our enemies openly declare their intent to make us leave our homeland. But that is a very unrealistic policy. The children of Yaakov, in the state that bears his name, certainly will follow his example until it finally brings quieter times and better relations.