#311 – part IV

Date and Place: 19 Sivan 5670 (1910), Yafo

Recipient and Background: Rav Yaakov David Wilovsky (Ridbaz), a leading rabbi who moved to Eretz Yisrael and was known for being, among other things, a strong opponent of leniencies on Shemitta. We have already seen three installments of why Rav Kook not only thought that the leniency of selling the land to obviate many of the laws of Shemitta was the correct approach under the circumstances but “fought” to make this seen as a fully legitimate ruling.

Body: After all I have written, I am hereby repeating, a second and a third time, that my entire desire and goal is only to cause people to look favorably on those Jews [who are being lenient]. This is especially true regarding the holy nation who are living in the courtyards of Hashem, on the holy mountain, which His right hand has acquired, that no one should cast aspersions on them, with the claim that they are overall evil and sinners.

On the other hand, I do not intend, Heaven forbid, to weaken the resolve of those who are upholding this great, holy mitzva (Shemitta), which after all the leniencies and creative ideas to justify them, has imbued in the mitzva the great light of liberation, salvation, and redemption for Hashem’s nation. My eyes always look forward to the joy and salvation Hashem will bring, when he founds the Jewish community of the Holy Land on a stable and strong basis and sends blessing and a flow of goodness. In this way, it will be possible to keep Shemitta properly with love without destroying or severely harming the community, but rather with blessing and quiet serenity.

I believe and hope that just as we view favorably [those who are being lenient] on earth, so too will the angels who serve as “defense attorneys,” who explain the good elements of a person’s actions, show how the Heavenly court should view them favorably. It is a great obligation of the Torah scholars and the righteous people of the generation to pray on behalf of the holy offspring who are compelled to follow this leniency, so that no damage or disease afflict them. This is in line with the prayer (Berachot 29a), “Whenever there is a difficult episode, may their needs be before you.” It is especially appropriate [to pray for them] considering that they are doing a practice based on a rabbinical ruling, and there is no phenomenon of separating oneself [from the community of observant Jews] to sin. Even if, Heaven forbid, our ruling is incorrect, “Hashem is great, and He will not be disgusted” (ibid. 8a).

I have relied on divine mercy that the more work is done to justify the actions of the lenient, along the lines of the Torah, (and we attach the prayers of the multitude on behalf of Hashem’s flock, which has returned to the fields where it grazed), so too the blessing will increase. This will turn the affliction to indulgence (a play on words in Hebrew), and the iniquity to great abundance of good (also a play on words) on Hashem’s nation and estate. This is because one cannot even estimate the great power of the righteous and the Torah scholars when they come to find virtue for Israel. About them, the pasuk says, “You did decree with your speech, and it will be established, and on your paths there will be an aura of light” (Iyov 22:28).

Friday, April 25, 2025

“The Nations in Uproar, Muttering in Vain”

by HaRav Dov Begon

Rosh HaYeshiva, Machon Meir

Rosh HaYeshiva, Machon Meir

Regarding the camel, it says: “Among the cud-chewing, hoofed animals, these are the ones that you may not eat: The camel shall be unclean to you although it brings up its cud, since it does not have a true hoof” (Vayikra 11:4). Regarding the pig it says, “The pig shall be unclean to you although it has a true split hoof, since it does not chew its cud” (v. 7). These two animals have marks of both the kosher animals and the nonkosher animals, but the Torah declares unequivocally, “They are unclean to you” (v. 8).

The pig and the camel allude to Christianity and Islam, respectively. Each of these religions boasts that its sources are within Judaism, and each uses the Bible and other Jewish sources to justify its existence. While Christianity spreads out its hooves like the pig, to show how kosher it is, it remains nonkosher on the inside, because it envisions G-d as being a man and claims that G-d abandoned Israel and forged a new covenant, Heaven forbid. Likewise, with Islam, it is true that in their worldview they oppose envisioning G-d as a man, and they claim that they believe in one G-d. Seemingly, they are kosher on the inside, yet when they raise-up the sword against Israel and against other nations, their true face is revealed, that of “his hand being against everyone and everyone’s hand being against him” (Beresheet 16:12).

Right now, Christianity and Islam share a common concern - how to deal with the rebirth of the Jewish People in Eretz Yisrael and its eternal capital Jerusalem, something which undermines the foundations of their worldview and faith. They are trying by various means, some ostensibly good and peace-like, and others openly wicked and bellicose, to nullify the counsel of G-d. Yet G-d, who loves His people and thinks only good of them, is raising them up to rebirth.

Indeed, it was in response to such plotting that Dovid HaMelech, sweet singer of Israel, said, “Why are the nations in uproar? Why do the peoples mutter in vain? The kings of the earth join ranks and the rulers take counsel together, against the L-rd and against His anointed” (Tehilim 2:1-2). Yet, “He who sits in the heavens laughs; the L-rd holds them in derision. He shall speak to them in His wrath and terrify them in His burning anger” (Ibid., v. 4-5). The Jewish People are G-d’s firstborn son, and they are forever as dear to Him as an infant is to its parents on the day of its birth (see Metzudot David, Ibid.).

Besorot Tovot,

Shabbat Shalom and Chodesh Tov,

Looking forward to complete salvation,

With the Love of Am Yisrael and Eretz Yisrael.

The pig and the camel allude to Christianity and Islam, respectively. Each of these religions boasts that its sources are within Judaism, and each uses the Bible and other Jewish sources to justify its existence. While Christianity spreads out its hooves like the pig, to show how kosher it is, it remains nonkosher on the inside, because it envisions G-d as being a man and claims that G-d abandoned Israel and forged a new covenant, Heaven forbid. Likewise, with Islam, it is true that in their worldview they oppose envisioning G-d as a man, and they claim that they believe in one G-d. Seemingly, they are kosher on the inside, yet when they raise-up the sword against Israel and against other nations, their true face is revealed, that of “his hand being against everyone and everyone’s hand being against him” (Beresheet 16:12).

Right now, Christianity and Islam share a common concern - how to deal with the rebirth of the Jewish People in Eretz Yisrael and its eternal capital Jerusalem, something which undermines the foundations of their worldview and faith. They are trying by various means, some ostensibly good and peace-like, and others openly wicked and bellicose, to nullify the counsel of G-d. Yet G-d, who loves His people and thinks only good of them, is raising them up to rebirth.

Indeed, it was in response to such plotting that Dovid HaMelech, sweet singer of Israel, said, “Why are the nations in uproar? Why do the peoples mutter in vain? The kings of the earth join ranks and the rulers take counsel together, against the L-rd and against His anointed” (Tehilim 2:1-2). Yet, “He who sits in the heavens laughs; the L-rd holds them in derision. He shall speak to them in His wrath and terrify them in His burning anger” (Ibid., v. 4-5). The Jewish People are G-d’s firstborn son, and they are forever as dear to Him as an infant is to its parents on the day of its birth (see Metzudot David, Ibid.).

Besorot Tovot,

Shabbat Shalom and Chodesh Tov,

Looking forward to complete salvation,

With the Love of Am Yisrael and Eretz Yisrael.

Caught up in the passion of the moment

by Rav Binny Freedman

There is a little-known test that officer cadets undergo in one form or another during Infantry Officer’s training that they almost always fail; which is precisely the point. It takes many forms so that one class will never be forewarned by the previous one. Mine was administered near the midpoint of a horrible experience known as bochan Aricha.

We were dropped in the middle of the desert and after a ten-kilometer run (more like a jog), within sight of a tent we presumed to be our objective, we were suddenly told we were under chemical attack and made to don our gas masks. Our commanders would often change the rules of the game and throw unexpected surprises at us, to test our resilience and ability to cope with unexpected situations.

It is hard to describe what it is like to run and fight in a gas mask; you are already exhausted, running on little sleep and in the heat of the desert the gas mask makes it difficult to breathe. The plexiglass visor very quickly steams up making it difficult to see which made the sudden order to turn and climb the steep mountain that seemed to rise endlessly in front of us all the more difficult. But you are in Officer’s course, so that’s what you do. Halfway up they yelled that two of our number were injured (we were a squad of eight) so that in addition to our exhaustion, our inability to breathe properly, and the steep climb, we now had to divide up all our gear to allow for two ‘bodies’ to be carried.

As we neared the top, I found myself in the lead and heard one of the commanders yelling: “Come on! You’re almost there!” Mustering up my last reserves and feeling the passion of leading the squad up the hill, I grabbed and pulled the guy behind me and with a yell started moving as fast as I could up the last ten yards to the top.

Suddenly, three red smoke grenades popped, and two commanders acting as ‘the enemy’ took us out from close range. Five yards from the top, we had let our passion get ahold of us and forgotten the cardinal rule of always making sure we took pause to gain perspective. So, they sent us back down to the bottom, to do the whole thing again…

We had forgotten a cardinal rule and learned a second: The first is to always consider the best place for an ambush, because that is usually where the enemy will be waiting. (They waited till we were almost at the top, when we least expected it…)

And the second, is that you have to be careful never to let passion get in the way of the pause that allows for a healthy perspective.

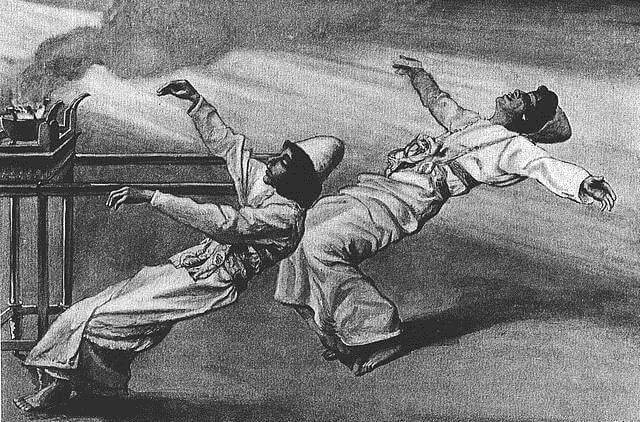

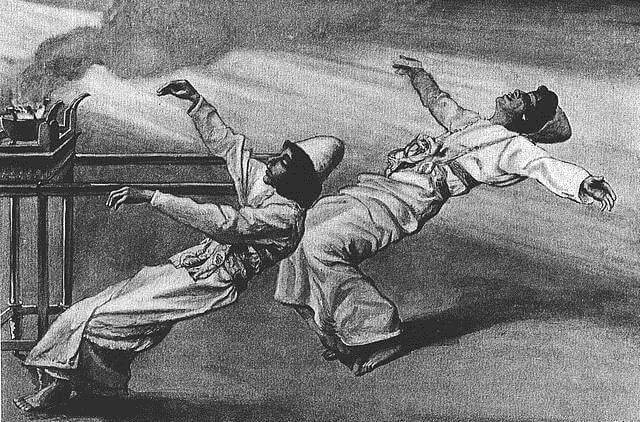

This week’s portion Shemini, contains one of the most tragic and challenging episodes in the Torah: the deaths of Nadav and Avihu, the sons of Aaron. In the midst of the dedication of the Mishkan as the Jewish people are celebrating the consecration of the Mishkan, and the initiation of the Kohanim (the priestly caste) along with the installation of the Jewish people’s beloved Aharon as the Kohein Gadol, the High priest, Nadav and Avihu, his two oldest sons, offer up a strange fire, of which they had not been commanded. (Vayikra 10:1)

Suddenly (ibid. v. 2) a fire comes from before G-d (possibly from the Kodesh Kedoshim) and consumes them in front of the entire Jewish people. In a moment, joy has been transformed into tragedy, and Aharon, on what should have been the greatest day of his life, is left speechless in the face of such an overwhelming tragedy.

The commentaries offer many different opinions as to what exactly happened here. Did they ignore their teacher Moshe? Were they drunk? Perhaps their transgression was one of arrogance? Interestingly, the language of the verse (“And fire came from before G-d and consumed them…”), mirroring exactly the words two verses earlier describing the acceptance by G-d of the people’s offering over which the Jewish people rejoiced en masse (ibid. 9:24), suggests that there was something positive in what they were doing despite their tragic end; they were somehow accepted by G-d as opposed to a standard transgression that would more likely result in a distancing from G-d.

Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch suggests that they were too caught up in the passion of the moment. Think about it: according to some commentaries (most notably Rashi) the building of the Mishkan was a direct consequence of the debacle of the Golden calf. Indeed, it appears in the Torah that the Jewish people were distant, even estranged from Hashem after the Golden Calf. In fact, it seems that in the half a year it takes the Jewish people to build the Mishkan, Hashem stops speaking with them, which must have been extremely painful for a people that had become so close to G-d they actually heard Him speak the Ten Commandments.

So when a fire comes from before G-d and consumes their offering, the Torah tells us (ibid.) “the entire nation rejoiced and fell on their faces…” It was a moment of extreme joy; of pure rejoicing, even love. And in the midst of all this, Nadav and Avihu, who actually represent the future leadership of the Jewish people, and who themselves have just been consecrated as Kohanim, are totally caught up in the moment. They are so full of joy, suggests Rav Hirsch, that their passion gets away from them; the offering of the people is not enough; they want to offer even more. So they take incense and attempt to offer up an additional offering which has not been commanded.

But true leaders should not need to be more passionate and rejoice more than the people, they should rather, exult in the joy of the people, with the people. And this is their undoing. They let their passion get away from them, when they should perhaps have used the opportunity for a pause, allowing a healthier perspective.

One wonders, in the moment before it all came apart, what the people felt, seeing these two young Priests grabbing their own fire and leaping forward in front of and seemingly above, everyone else.

I recall once at a wedding seeing something that really bothered me. The bride and groom had just re-entered the wedding hall after the ceremony and the entire hall erupted in song and dance in an expression of pure joy. The groom grabbed his father and then a couple of his brothers and they were dancing with the most wonderful expressions of happiness on their faces when a well-known rabbi who had missed the ceremony arrived, pushed his way through the outer circles of dancing into the middle, grabbed the father and the groom and started madly dancing with them.

It took me a while to realize what had bothered me about the moment (though of course only Hashem knows what is in the hearts of men; so this about my perception more than whether it is really true). His excitement had been so great he missed the fact that he was interrupting what might have been a really beautiful moment. His passion had carried him away when perhaps a pause might better have been in order.

And this is true not only in positive experiences but in the midst of negative moments as well. As an example, it is no accident that Rambam, immediately after describing in his laws of character traits (Hilchot Deot 2:3) how anger is an extremely negative quality that must be avoided at all costs, begins to describe the value of silence.

“A person should always practice a healthy and abundant modicum of silence…” (ibid. 2:4). Implying that the first way to deal with anger is silence. Words spoken and actions taken in anger are almost always regretted. We usually are sure, later upon reflection, that we could have done a better job if we had waited until we were no longer angry, before responding.

Words spoken in anger never come out right. They are always better served after a healthy pause. Imagine how much better life would be if we simply made it a habit never to speak (or text) in anger; always to wait until we are no longer angry, or at least no longer in the heat of the moment. How many foolish and hurtful words would be avoided, and how much better we would be at expressing our thoughts…

Perhaps this is one of the messages we can take away from the painful episode of Nadav and Avihu: to temper our passions with healthy pauses, which will most always result in better perspectives.

Wishing you all a Shabbat Shalom from Jerusalem.

We were dropped in the middle of the desert and after a ten-kilometer run (more like a jog), within sight of a tent we presumed to be our objective, we were suddenly told we were under chemical attack and made to don our gas masks. Our commanders would often change the rules of the game and throw unexpected surprises at us, to test our resilience and ability to cope with unexpected situations.

It is hard to describe what it is like to run and fight in a gas mask; you are already exhausted, running on little sleep and in the heat of the desert the gas mask makes it difficult to breathe. The plexiglass visor very quickly steams up making it difficult to see which made the sudden order to turn and climb the steep mountain that seemed to rise endlessly in front of us all the more difficult. But you are in Officer’s course, so that’s what you do. Halfway up they yelled that two of our number were injured (we were a squad of eight) so that in addition to our exhaustion, our inability to breathe properly, and the steep climb, we now had to divide up all our gear to allow for two ‘bodies’ to be carried.

As we neared the top, I found myself in the lead and heard one of the commanders yelling: “Come on! You’re almost there!” Mustering up my last reserves and feeling the passion of leading the squad up the hill, I grabbed and pulled the guy behind me and with a yell started moving as fast as I could up the last ten yards to the top.

Suddenly, three red smoke grenades popped, and two commanders acting as ‘the enemy’ took us out from close range. Five yards from the top, we had let our passion get ahold of us and forgotten the cardinal rule of always making sure we took pause to gain perspective. So, they sent us back down to the bottom, to do the whole thing again…

We had forgotten a cardinal rule and learned a second: The first is to always consider the best place for an ambush, because that is usually where the enemy will be waiting. (They waited till we were almost at the top, when we least expected it…)

And the second, is that you have to be careful never to let passion get in the way of the pause that allows for a healthy perspective.

This week’s portion Shemini, contains one of the most tragic and challenging episodes in the Torah: the deaths of Nadav and Avihu, the sons of Aaron. In the midst of the dedication of the Mishkan as the Jewish people are celebrating the consecration of the Mishkan, and the initiation of the Kohanim (the priestly caste) along with the installation of the Jewish people’s beloved Aharon as the Kohein Gadol, the High priest, Nadav and Avihu, his two oldest sons, offer up a strange fire, of which they had not been commanded. (Vayikra 10:1)

Suddenly (ibid. v. 2) a fire comes from before G-d (possibly from the Kodesh Kedoshim) and consumes them in front of the entire Jewish people. In a moment, joy has been transformed into tragedy, and Aharon, on what should have been the greatest day of his life, is left speechless in the face of such an overwhelming tragedy.

The commentaries offer many different opinions as to what exactly happened here. Did they ignore their teacher Moshe? Were they drunk? Perhaps their transgression was one of arrogance? Interestingly, the language of the verse (“And fire came from before G-d and consumed them…”), mirroring exactly the words two verses earlier describing the acceptance by G-d of the people’s offering over which the Jewish people rejoiced en masse (ibid. 9:24), suggests that there was something positive in what they were doing despite their tragic end; they were somehow accepted by G-d as opposed to a standard transgression that would more likely result in a distancing from G-d.

Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch suggests that they were too caught up in the passion of the moment. Think about it: according to some commentaries (most notably Rashi) the building of the Mishkan was a direct consequence of the debacle of the Golden calf. Indeed, it appears in the Torah that the Jewish people were distant, even estranged from Hashem after the Golden Calf. In fact, it seems that in the half a year it takes the Jewish people to build the Mishkan, Hashem stops speaking with them, which must have been extremely painful for a people that had become so close to G-d they actually heard Him speak the Ten Commandments.

So when a fire comes from before G-d and consumes their offering, the Torah tells us (ibid.) “the entire nation rejoiced and fell on their faces…” It was a moment of extreme joy; of pure rejoicing, even love. And in the midst of all this, Nadav and Avihu, who actually represent the future leadership of the Jewish people, and who themselves have just been consecrated as Kohanim, are totally caught up in the moment. They are so full of joy, suggests Rav Hirsch, that their passion gets away from them; the offering of the people is not enough; they want to offer even more. So they take incense and attempt to offer up an additional offering which has not been commanded.

But true leaders should not need to be more passionate and rejoice more than the people, they should rather, exult in the joy of the people, with the people. And this is their undoing. They let their passion get away from them, when they should perhaps have used the opportunity for a pause, allowing a healthier perspective.

One wonders, in the moment before it all came apart, what the people felt, seeing these two young Priests grabbing their own fire and leaping forward in front of and seemingly above, everyone else.

I recall once at a wedding seeing something that really bothered me. The bride and groom had just re-entered the wedding hall after the ceremony and the entire hall erupted in song and dance in an expression of pure joy. The groom grabbed his father and then a couple of his brothers and they were dancing with the most wonderful expressions of happiness on their faces when a well-known rabbi who had missed the ceremony arrived, pushed his way through the outer circles of dancing into the middle, grabbed the father and the groom and started madly dancing with them.

It took me a while to realize what had bothered me about the moment (though of course only Hashem knows what is in the hearts of men; so this about my perception more than whether it is really true). His excitement had been so great he missed the fact that he was interrupting what might have been a really beautiful moment. His passion had carried him away when perhaps a pause might better have been in order.

And this is true not only in positive experiences but in the midst of negative moments as well. As an example, it is no accident that Rambam, immediately after describing in his laws of character traits (Hilchot Deot 2:3) how anger is an extremely negative quality that must be avoided at all costs, begins to describe the value of silence.

“A person should always practice a healthy and abundant modicum of silence…” (ibid. 2:4). Implying that the first way to deal with anger is silence. Words spoken and actions taken in anger are almost always regretted. We usually are sure, later upon reflection, that we could have done a better job if we had waited until we were no longer angry, before responding.

Words spoken in anger never come out right. They are always better served after a healthy pause. Imagine how much better life would be if we simply made it a habit never to speak (or text) in anger; always to wait until we are no longer angry, or at least no longer in the heat of the moment. How many foolish and hurtful words would be avoided, and how much better we would be at expressing our thoughts…

Perhaps this is one of the messages we can take away from the painful episode of Nadav and Avihu: to temper our passions with healthy pauses, which will most always result in better perspectives.

Wishing you all a Shabbat Shalom from Jerusalem.

Holy Fire, Unholy Lies

by Rabbi Steven Pruzansky

(First published at Israelnationalnews.com)

There is literally no respite from the lies of our enemies.

This holiday season, as always, brought thousands of pilgrims, tourists, and worshippers to all parts of Jerusalem to share in the festivities of the holidays of Passover and Easter. And, as always, it elicited from Israel’s enemies a torrent of lies, provocations, and baseless accusations, all of which deserve to be refuted.

The three-day Easter celebration was marked by thousands of Christian pilgrims enjoying Good Friday services, Holy Fire observances, and Easter Sunday in Jerusalem’s Old City, with special concentration on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. But a host of Arab provocateurs rushed to the media to complain about hundreds of people turned away by Israeli police, including the Papal Nuncio, from entry into the Church. Some of the protesters turned violent and claimed that Israel was defiantly interfering with Christian freedom of worship.

There is a kernel of truth to the accusation that entry to the Church was restricted by Israeli authorities – but not for the reasons ascribed to Israel by the provocateurs. By prior agreement, admission to the ancient church for the Holy Fire ceremony was limited to 2,200 people who had received prior authorization, with another 1300 allowed to access the outer courtyard and the roof. Such limitations are common throughout the world – museums, today, are a typical example – and prior authorization for entry is common at synagogues in Europe and the Americas. These restrictions are imposed for security reasons, and not only to defuse the threat of Arab terror, but rather to protect the worshippers from the potentially deadly effects of overcrowding.

Indeed, entry to the Saudi Arabian city of Mecca is barred to all non-Muslims, but even the number of Muslim visitors to Mecca and the Grand Mosque are severely restricted during the holiday seasons out of concern for the safety and security of pilgrims. This year, entry to the city of Mecca is forbidden beginning on April 25 and through the month-long Hajj season, to any Muslim who does not possess a valid work permit, a Mecca residency ID, or a valid Hajj permit. But enemies of Israel only perceive tourist restrictions in Israel of any sort as problematic and offensive.

As is known, the interior of the Church is a very confined space, and subdivided – to the inch – between some half-dozen Christian sects. The Holy Fire ceremony involves the kindling of a candle, with the fire then shared with the various groups until hundreds of candles are lit in this small area. In 1834 - unfortunately for our enemies, long before the State of Israel could be blamed – hundreds of Christian pilgrims died in a stampede caused after fire spread throughout the Church at a Holy Fire observance. The restrictions are designed to avoid the recurrence of such a tragedy.

Israel is especially mindful of the dangers inherent in mass crowds assembling in ancient structures. In 2021, forty-five Jewish men and boys were crushed to death, and more than one hundred injured, when celebrants fell on slippery steps at Rabbi Shimon’s tomb in Meron causing a stampede. That is why limitations are imposed at such locations. Imagine if there were no regulation of entry at the Church, and tragedy ensued, how these same critics would be lambasting Israel for its indifference to Christian life.

The enemies of Israel have it backwards. Rather than these restrictions indicating Israel’s interference with Christian worship, they instead testify to the concern for the life and well being of all tourists, pilgrims, and visitors to the Holy Land.

Israel should be lauded for its conduct here, not castigated.

(First published at Israelnationalnews.com)

There is literally no respite from the lies of our enemies.

This holiday season, as always, brought thousands of pilgrims, tourists, and worshippers to all parts of Jerusalem to share in the festivities of the holidays of Passover and Easter. And, as always, it elicited from Israel’s enemies a torrent of lies, provocations, and baseless accusations, all of which deserve to be refuted.

The three-day Easter celebration was marked by thousands of Christian pilgrims enjoying Good Friday services, Holy Fire observances, and Easter Sunday in Jerusalem’s Old City, with special concentration on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. But a host of Arab provocateurs rushed to the media to complain about hundreds of people turned away by Israeli police, including the Papal Nuncio, from entry into the Church. Some of the protesters turned violent and claimed that Israel was defiantly interfering with Christian freedom of worship.

There is a kernel of truth to the accusation that entry to the Church was restricted by Israeli authorities – but not for the reasons ascribed to Israel by the provocateurs. By prior agreement, admission to the ancient church for the Holy Fire ceremony was limited to 2,200 people who had received prior authorization, with another 1300 allowed to access the outer courtyard and the roof. Such limitations are common throughout the world – museums, today, are a typical example – and prior authorization for entry is common at synagogues in Europe and the Americas. These restrictions are imposed for security reasons, and not only to defuse the threat of Arab terror, but rather to protect the worshippers from the potentially deadly effects of overcrowding.

Indeed, entry to the Saudi Arabian city of Mecca is barred to all non-Muslims, but even the number of Muslim visitors to Mecca and the Grand Mosque are severely restricted during the holiday seasons out of concern for the safety and security of pilgrims. This year, entry to the city of Mecca is forbidden beginning on April 25 and through the month-long Hajj season, to any Muslim who does not possess a valid work permit, a Mecca residency ID, or a valid Hajj permit. But enemies of Israel only perceive tourist restrictions in Israel of any sort as problematic and offensive.

As is known, the interior of the Church is a very confined space, and subdivided – to the inch – between some half-dozen Christian sects. The Holy Fire ceremony involves the kindling of a candle, with the fire then shared with the various groups until hundreds of candles are lit in this small area. In 1834 - unfortunately for our enemies, long before the State of Israel could be blamed – hundreds of Christian pilgrims died in a stampede caused after fire spread throughout the Church at a Holy Fire observance. The restrictions are designed to avoid the recurrence of such a tragedy.

Israel is especially mindful of the dangers inherent in mass crowds assembling in ancient structures. In 2021, forty-five Jewish men and boys were crushed to death, and more than one hundred injured, when celebrants fell on slippery steps at Rabbi Shimon’s tomb in Meron causing a stampede. That is why limitations are imposed at such locations. Imagine if there were no regulation of entry at the Church, and tragedy ensued, how these same critics would be lambasting Israel for its indifference to Christian life.

The enemies of Israel have it backwards. Rather than these restrictions indicating Israel’s interference with Christian worship, they instead testify to the concern for the life and well being of all tourists, pilgrims, and visitors to the Holy Land.

Israel should be lauded for its conduct here, not castigated.

Thursday, April 24, 2025

Rubio torpedoes the left’s anti-Israel stronghold inside the State Department

by Jonathan Tobin

The administration isn’t abandoning the cause of human rights. A reorganization will stop bureaucratic ideologues from using the government to attack the Jewish state.

For decades, a group of so-called “human rights” organizations—in particular, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch—have been waging war on the State of Israel. As NGO Monitor, the authoritative source on the subject, has documented, these groups have conducted a multifaceted campaign involving support for boycotts across the board, smearing it as an “apartheid” state, and promoting its isolation and prosecution on the international stage.

In doing so, these non-governmental organizations and the liberal publications that continue to treat them as credible sources have succeeded in transforming human rights from a righteous cause into a movement that is a politically powerful, thinly veiled engine of 21st-century antisemitism.

Those who follow U.S. foreign policy have become all too aware of this development, especially since the Hamas-led Palestinian terrorist attacks and atrocities in southern Israel on Oct. 7, 2023. Since then, this bogus “human rights” lobby has stepped up its efforts to delegitimize Israel’s efforts to defend itself and acted as tacit advocates for Hamas in falsely depicting the war in Gaza and against other Iranian proxies in Lebanon and Yemen as acts of “genocide.”

Most Americans have been largely unaware that a band of activists with similar goals and beliefs to those at Human Rights Watch and Amnesty have been operating from a base inside the U.S. government. Thanks to a reorganization of the U.S. State Department, announced this week by Secretary of State Marco Rubio, that may now be coming to an end.

This is much to the dismay of liberal outlets like The New York Times, in addition to former Obama and Biden administration staffers who are horrified about what they consider to be a “blow to U.S. values.” According to the Times, the Trump administration is signaling that it “cares less about fundamental freedoms than it does about cutting deals with autocrats and tyrants.” In an article that largely consisted of quotes from foes of President Donald Trump and Rubio, the offices, such as the human-rights bureau, that are being pared down and stripped of their autonomy were described as “a sort of voice of conscience for policymakers as they balance America’s interests with its values.”

Opponents of Israel

Phrased in that manner, this sounds like something terrible—a scheme that would truly undermine American advocacy for freedom abroad. But the giveaway as to what’s really at stake in this controversy came in the next sentence of the article. As the newspaper put it: “During the Biden administration, it offered internal criticism of Israel, arguing that it was not doing enough to protect civilians in Gaza.”

In other words, these bureaus have acted as a powerful check on the ability of any president to advance the U.S.-Israel relationship as well as to promote a malicious and false narrative that, like those spewing from Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, seeks to demonize Israel and any other targets of the political left. Though they are being portrayed in the liberal press as courageous truth-tellers working to spread freedom and democracy abroad, such officials have been acting in the grand tradition of State Department antisemites and Arabists who have sought to work against the interests of Israel and the Jewish people since the 1930s.

As Rubio explained in a government Substack post, for the past few decades, the State Department has operated several bureaus that, “provided a fertile environment for activists to redefine ‘human rights’ and ‘democracy,” to conform to the ideology of the same so-called “progressives” who have captured control of academia.

Often pursuing goals completely at odds with the foreign-policy objectives of the president and secretary of state, this growing band of biased bureaucratic ideologues has wielded considerable power and influence. To the frustration of those who understand the way that their agenda damages U.S. interests and allies, they’ve made a significant sector of the federal establishment into bastions of hostility to Israel and the governments of other nations that have been targets of the left, such as Hungary, Poland and Brazil. It also promoted policies that, as Rubio pointed out, “funneled millions of taxpayer dollars to international organizations and NGOs that facilitated mass migration around the world, including the invasion on our southern border.”

How could that be? And why has it taken so long for someone in authority to order changes like those that the current administration has put forward?

How rogue elements ruled

The answer to that question is fairly simple. Until now, no one in the White House or at the head of the State Department has tried to rein in what Rubio rightly termed “rogue” elements within the government.

They have operated with the impunity that comes with civil-service protections and the fact that past administrations either lacked the will or ability to restrain a powerful bureaucracy. As is true in almost all governmental departments and agencies, the permanent employees lean hard to the left. They also have managed to fend off any efforts to control them by manipulating the political appointees, who are supposed to be their bosses, treating them as incompetent amateurs who know little about how the government works in much the same manner as the characters in the classic British political comedy “Yes, Minister.”

It’s also true that, at least in principle, both the Obama and Biden administrations had no problem with this “human rights” lobby inside the State Department because they largely agreed with them.

Yet the inherent problem of having a portion of the government conducting an ideological foreign policy largely independent of the people at the top of the organizational flow chart became exposed in the last 16 months of Biden’s term in office. That’s because the anti-Israel bureaucrats, like the pro-Hamas mobs on college campuses, believed that the administration of President Joe Biden was insufficiently hostile to Israel after Oct. 7.

Biden’s civil war

As soon became apparent, the barbaric attack on Israeli civilians and the war to eradicate Hamas that followed had fomented nothing less than a civil war within the administration. Large portions of the permanent foreign-policy bureaucracy, as well as many of Biden’s political appointees ensconced in positions below the rank of cabinet and undersecretary rank, simply opposed the ambivalent Biden stand on the war, in which he publicly opposed Hamas but at the same time didn’t want Israel to succeed in defeating it. They wanted a complete cutoff of U.S. aid and an American-imposed ceasefire that would enable Hamas to both survive the war they started and even to win it.

While some officials, including members of the State Department’s human-rights bureau, resigned in protest over Biden’s half-hearted support of Israel, most remained in place. They continued working to undermine that stand and help fund projects that would hurt Israel and aid Palestinians fighting it, including, as one Middle East Forum study noted, indirectly financing anti-Israel terrorism. Indeed, as the City Journal reported in February, USAID was directing American taxpayer dollars to Hamas.

That is the context with which Rubio’s reorganization should be understood.

One aspect of the scheme is that it will eliminate redundancies and reduce costs in keeping with the mandate of Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), initially guided by billionaire Elon Musk.

Backing human rights

Rubio, who, as the Times noted, was an ardent supporter of human rights and encouraged using American power to advocate for freedom abroad during his 14 years in the U.S. Senate. Contrary to the assertions of his critics, he has not changed his mind about the importance of the issue. Rather, he is attempting to rescue the cause of human rights and democracy from activists who have turned it into a crusade against Israel and other governments, such as that of Hungary, which is falsely labeled as authoritarian because of its resistance to left-wing attempts to undermine its national identity.

Rubio’s plan involves a massive shift that he hopes will end the radical power base inside the State Department by stripping it of its autonomy and putting it inside existing regional bureaus, where it won’t be free to undermine Trump’s pro-Israel policy or fund groups working to promote policies and ideas antithetical to U.S. interests.

Under Rubio’s plan, there will still be plenty of people at the State Department who will be tasked with monitoring human rights around the world and seeking to promote American values of liberty, including political and economic freedom. The administration will also preserve the office of the special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism. Reportedly, it will shift to a global Jewish affairs coordinator rather than the old division under the office of the undersecretary of civilian security, human rights and democracy—a section of Foggy Bottom that was a major part of the problem Rubio is trying to solve. The Office of International Religious Freedom will also still be there.

Will Rubio succeed in taming and redirecting the energy of the diplomatic bureaucracy away from toxic left-wing activism and toward efforts that will promote American interests and strengthen U.S. ties with Israel and other allies? Only time will tell, but as Trump has demonstrated on other issues, such as his efforts to reform or defund academic institutions that tolerate and encourage antisemitism, enacting such fundamental changes requires bold strokes and decisive leadership.

For far too long, the administrative state, of which the left-wing elements in the State Department were a key part, ruled as an unelected and unaccountable fourth branch of the U.S. government that was dedicated to pursuing left-wing policies that no one had voted for. Trump and Rubio have rightly decided this has to end.

Their actions will provoke much consternation and pearl-clutching from the foreign-policy establishment and its liberal media cheerleaders. But their taking an axe to a portion of the State Department bureaucracy run by radicals is a victory for friends of Israel and American interests, and a clear defeat for their opponents who operate under the false flag of “human rights” advocacy.

The administration isn’t abandoning the cause of human rights. A reorganization will stop bureaucratic ideologues from using the government to attack the Jewish state.

For decades, a group of so-called “human rights” organizations—in particular, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch—have been waging war on the State of Israel. As NGO Monitor, the authoritative source on the subject, has documented, these groups have conducted a multifaceted campaign involving support for boycotts across the board, smearing it as an “apartheid” state, and promoting its isolation and prosecution on the international stage.

In doing so, these non-governmental organizations and the liberal publications that continue to treat them as credible sources have succeeded in transforming human rights from a righteous cause into a movement that is a politically powerful, thinly veiled engine of 21st-century antisemitism.

Those who follow U.S. foreign policy have become all too aware of this development, especially since the Hamas-led Palestinian terrorist attacks and atrocities in southern Israel on Oct. 7, 2023. Since then, this bogus “human rights” lobby has stepped up its efforts to delegitimize Israel’s efforts to defend itself and acted as tacit advocates for Hamas in falsely depicting the war in Gaza and against other Iranian proxies in Lebanon and Yemen as acts of “genocide.”

Most Americans have been largely unaware that a band of activists with similar goals and beliefs to those at Human Rights Watch and Amnesty have been operating from a base inside the U.S. government. Thanks to a reorganization of the U.S. State Department, announced this week by Secretary of State Marco Rubio, that may now be coming to an end.

This is much to the dismay of liberal outlets like The New York Times, in addition to former Obama and Biden administration staffers who are horrified about what they consider to be a “blow to U.S. values.” According to the Times, the Trump administration is signaling that it “cares less about fundamental freedoms than it does about cutting deals with autocrats and tyrants.” In an article that largely consisted of quotes from foes of President Donald Trump and Rubio, the offices, such as the human-rights bureau, that are being pared down and stripped of their autonomy were described as “a sort of voice of conscience for policymakers as they balance America’s interests with its values.”

Opponents of Israel

Phrased in that manner, this sounds like something terrible—a scheme that would truly undermine American advocacy for freedom abroad. But the giveaway as to what’s really at stake in this controversy came in the next sentence of the article. As the newspaper put it: “During the Biden administration, it offered internal criticism of Israel, arguing that it was not doing enough to protect civilians in Gaza.”

In other words, these bureaus have acted as a powerful check on the ability of any president to advance the U.S.-Israel relationship as well as to promote a malicious and false narrative that, like those spewing from Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, seeks to demonize Israel and any other targets of the political left. Though they are being portrayed in the liberal press as courageous truth-tellers working to spread freedom and democracy abroad, such officials have been acting in the grand tradition of State Department antisemites and Arabists who have sought to work against the interests of Israel and the Jewish people since the 1930s.

As Rubio explained in a government Substack post, for the past few decades, the State Department has operated several bureaus that, “provided a fertile environment for activists to redefine ‘human rights’ and ‘democracy,” to conform to the ideology of the same so-called “progressives” who have captured control of academia.

Often pursuing goals completely at odds with the foreign-policy objectives of the president and secretary of state, this growing band of biased bureaucratic ideologues has wielded considerable power and influence. To the frustration of those who understand the way that their agenda damages U.S. interests and allies, they’ve made a significant sector of the federal establishment into bastions of hostility to Israel and the governments of other nations that have been targets of the left, such as Hungary, Poland and Brazil. It also promoted policies that, as Rubio pointed out, “funneled millions of taxpayer dollars to international organizations and NGOs that facilitated mass migration around the world, including the invasion on our southern border.”

How could that be? And why has it taken so long for someone in authority to order changes like those that the current administration has put forward?

How rogue elements ruled

The answer to that question is fairly simple. Until now, no one in the White House or at the head of the State Department has tried to rein in what Rubio rightly termed “rogue” elements within the government.

They have operated with the impunity that comes with civil-service protections and the fact that past administrations either lacked the will or ability to restrain a powerful bureaucracy. As is true in almost all governmental departments and agencies, the permanent employees lean hard to the left. They also have managed to fend off any efforts to control them by manipulating the political appointees, who are supposed to be their bosses, treating them as incompetent amateurs who know little about how the government works in much the same manner as the characters in the classic British political comedy “Yes, Minister.”

It’s also true that, at least in principle, both the Obama and Biden administrations had no problem with this “human rights” lobby inside the State Department because they largely agreed with them.

Yet the inherent problem of having a portion of the government conducting an ideological foreign policy largely independent of the people at the top of the organizational flow chart became exposed in the last 16 months of Biden’s term in office. That’s because the anti-Israel bureaucrats, like the pro-Hamas mobs on college campuses, believed that the administration of President Joe Biden was insufficiently hostile to Israel after Oct. 7.

Biden’s civil war

As soon became apparent, the barbaric attack on Israeli civilians and the war to eradicate Hamas that followed had fomented nothing less than a civil war within the administration. Large portions of the permanent foreign-policy bureaucracy, as well as many of Biden’s political appointees ensconced in positions below the rank of cabinet and undersecretary rank, simply opposed the ambivalent Biden stand on the war, in which he publicly opposed Hamas but at the same time didn’t want Israel to succeed in defeating it. They wanted a complete cutoff of U.S. aid and an American-imposed ceasefire that would enable Hamas to both survive the war they started and even to win it.

While some officials, including members of the State Department’s human-rights bureau, resigned in protest over Biden’s half-hearted support of Israel, most remained in place. They continued working to undermine that stand and help fund projects that would hurt Israel and aid Palestinians fighting it, including, as one Middle East Forum study noted, indirectly financing anti-Israel terrorism. Indeed, as the City Journal reported in February, USAID was directing American taxpayer dollars to Hamas.

That is the context with which Rubio’s reorganization should be understood.

One aspect of the scheme is that it will eliminate redundancies and reduce costs in keeping with the mandate of Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), initially guided by billionaire Elon Musk.

Backing human rights

Rubio, who, as the Times noted, was an ardent supporter of human rights and encouraged using American power to advocate for freedom abroad during his 14 years in the U.S. Senate. Contrary to the assertions of his critics, he has not changed his mind about the importance of the issue. Rather, he is attempting to rescue the cause of human rights and democracy from activists who have turned it into a crusade against Israel and other governments, such as that of Hungary, which is falsely labeled as authoritarian because of its resistance to left-wing attempts to undermine its national identity.

Rubio’s plan involves a massive shift that he hopes will end the radical power base inside the State Department by stripping it of its autonomy and putting it inside existing regional bureaus, where it won’t be free to undermine Trump’s pro-Israel policy or fund groups working to promote policies and ideas antithetical to U.S. interests.

Under Rubio’s plan, there will still be plenty of people at the State Department who will be tasked with monitoring human rights around the world and seeking to promote American values of liberty, including political and economic freedom. The administration will also preserve the office of the special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism. Reportedly, it will shift to a global Jewish affairs coordinator rather than the old division under the office of the undersecretary of civilian security, human rights and democracy—a section of Foggy Bottom that was a major part of the problem Rubio is trying to solve. The Office of International Religious Freedom will also still be there.

Will Rubio succeed in taming and redirecting the energy of the diplomatic bureaucracy away from toxic left-wing activism and toward efforts that will promote American interests and strengthen U.S. ties with Israel and other allies? Only time will tell, but as Trump has demonstrated on other issues, such as his efforts to reform or defund academic institutions that tolerate and encourage antisemitism, enacting such fundamental changes requires bold strokes and decisive leadership.

For far too long, the administrative state, of which the left-wing elements in the State Department were a key part, ruled as an unelected and unaccountable fourth branch of the U.S. government that was dedicated to pursuing left-wing policies that no one had voted for. Trump and Rubio have rightly decided this has to end.

Their actions will provoke much consternation and pearl-clutching from the foreign-policy establishment and its liberal media cheerleaders. But their taking an axe to a portion of the State Department bureaucracy run by radicals is a victory for friends of Israel and American interests, and a clear defeat for their opponents who operate under the false flag of “human rights” advocacy.

Wednesday, April 23, 2025

How many times can someone be chaiv missa—culpable of death?

by Rabbi Pinchas Winston

TALK ABOUT ENTANGLEMENT. The simple narrative has Nadav and Avihu dying because they brought an “unauthorized fire” during the inauguration ceremony in this week’s parsha. In Devarim, it mentions that they died because Aharon participated in the incident of the golden calf, even though he had all the right intentions. In Parashas Mishpatim, it says that Nadav and Avihu were already destined to be killed because, while on Har Sinai, they glanced at the Shechinah. How many times can someone be chaiv missa—culpable of death?

Even more confusing is how such great people could be worthy of death even once? True, the Gemora portrays them as being someone pompous, not at all like their great and humble father. But Moshe Rabbeinu called them great and holy people, and Kabbalah concurs. According to the Arizal, anyone who received their souls after their deaths gained the power of prophecy. Those are great souls.

You find this a lot in Torah Judaism. Things taken by themselves are often simple and logical. But when the same things are taken with others, all of a sudden difficulties arise, even what appear like contradictions. It’s why some prefer to live with the smaller picture, in order to avoid having to work out issues that arise with the bigger picture.

Even the Gemara addresses the issue of conflicting mitzvos. Sometimes, a situation makes possible two mitzvos, but doing one makes it impossible to do the other. Which takes precedence? There are rules.

Even Aharon HaKohen was faced with such a situation. On one hand, he wasn’t allowed to be involved in the building of the golden calf, even his intentions were pure. On the other hand, had he refused the demands of the people and they killed him, the generation would not have been able to atone for itself and would have been destroyed, which he believed was unacceptable to God. Which issue mattered more to God?

This year, the fourteenth of Nisan was also Shabbos. When it is not, disposing of chametz is easy and can even be done before the fourteenth. But we needed to have three bread meals for the honor of Shabbos on the fourteenth this year, after the house was already cleaned for Pesach. And we couldn’t use Kosher L’Pesach matzah because we cannot eat matzah the day before the Seder.

This halachic quandary has solutions, each of which is a compromise of sorts. Some bakeries made crumbless little challos. Some people ate pitos out of plastic bags. Some had matzah ashirah (egg matzos). Each solution had its advantages and disadvantages.

Whatever the solution, people had to think about it. The Rav of my shul printed pages that summarized many of the relevant halachos of that particular Shabbos HaGadol; many haven’t forgotten what they did the previous time that fourteenth of Nisan fell on Shabbos. I bet you there were people who usually didn’t do much about Seudas Shlishis the rest of the year who had one this year, because of the situation.

The Gemara itself is full of machlokes—disagreements. This is one of the reasons why you cannot decide a halacha based upon the Gemara, but from the Poskim who learned the Gemara and all the relevant commentaries since then. So many halachos today are simply the rabbis playing it safe, deciding like the more stringent opinion as to cover all bases. Thus is the reality of Torah as the exile deepens.

Then of course there is eilu v’eilu divrei Elokim chaim—these and these are the words of the living God. It’s when two opinions seem to contradict one another and yet are both true—to God. It’s like saying that, as much as they seem like a contradiction down here to us, higher up they work together beautifully.

As a Torah Jew, you just go with it. As a student of Kabbalah, you get used to it. Everything becomes easier to deal with once you not only acknowledge you don’t know enough to answer all the questions, you even understand how much more there is to know to answer even just most of the questions.

Once, between Mincha and Ma’ariv, I picked up the Pachad Yitzchak on Chanukah. The holiday was coming and I just felt like getting some deep insight I had never considered before. Among the few things I saw at that time, there was a ma’amer on the disagreements in Shas (all of Gemora), and what Rav Hutner, zt”l, pointed out blew me away.

Yes, we don’t like machlokes, he was basically saying. But think of all the Torah that has been brought to light because of it!

So true. All of a sudden, what I had simply attributed to something bad, the loss of Torah clarity, I saw as indirect, seemingly deliberate means for increasing Torah in the world. I don’t get them often, but that was one of those moments when you feel the beauty of an idea throughout your entire body. It didn’t just alter my perspective on machlokes, but on adversity in general.

The Torah promotes shalom bayis on all levels. It encourages the resolution of conflict, or the avoidance of it altogether. It paints a picture of a picture-perfect life, and promises one in the next world, even beginning with the Messianic Era. But God’s route to all of that is often very different than the one we imagined, even harshly different.

Even the episode with Nadav and Avihu at one of the holiest moments in human history makes this point. Human mistakes were made, but one has to wonder what God’s role was in all of this. We didn’t plan what happened and we certainly didn’t like the outcome? But did God, given the longer term plan of history?

We’ll have to wait to answer those questions, but in the meantime, each of the pieces of the puzzle, even if they don’t seem to fit together, teaches us something we need to know about life, God, and Torah. Because when it is all said and done, isn’t that the one thing we can do something about?

Even more confusing is how such great people could be worthy of death even once? True, the Gemora portrays them as being someone pompous, not at all like their great and humble father. But Moshe Rabbeinu called them great and holy people, and Kabbalah concurs. According to the Arizal, anyone who received their souls after their deaths gained the power of prophecy. Those are great souls.

You find this a lot in Torah Judaism. Things taken by themselves are often simple and logical. But when the same things are taken with others, all of a sudden difficulties arise, even what appear like contradictions. It’s why some prefer to live with the smaller picture, in order to avoid having to work out issues that arise with the bigger picture.

Even the Gemara addresses the issue of conflicting mitzvos. Sometimes, a situation makes possible two mitzvos, but doing one makes it impossible to do the other. Which takes precedence? There are rules.

Even Aharon HaKohen was faced with such a situation. On one hand, he wasn’t allowed to be involved in the building of the golden calf, even his intentions were pure. On the other hand, had he refused the demands of the people and they killed him, the generation would not have been able to atone for itself and would have been destroyed, which he believed was unacceptable to God. Which issue mattered more to God?

This year, the fourteenth of Nisan was also Shabbos. When it is not, disposing of chametz is easy and can even be done before the fourteenth. But we needed to have three bread meals for the honor of Shabbos on the fourteenth this year, after the house was already cleaned for Pesach. And we couldn’t use Kosher L’Pesach matzah because we cannot eat matzah the day before the Seder.

This halachic quandary has solutions, each of which is a compromise of sorts. Some bakeries made crumbless little challos. Some people ate pitos out of plastic bags. Some had matzah ashirah (egg matzos). Each solution had its advantages and disadvantages.

Whatever the solution, people had to think about it. The Rav of my shul printed pages that summarized many of the relevant halachos of that particular Shabbos HaGadol; many haven’t forgotten what they did the previous time that fourteenth of Nisan fell on Shabbos. I bet you there were people who usually didn’t do much about Seudas Shlishis the rest of the year who had one this year, because of the situation.

The Gemara itself is full of machlokes—disagreements. This is one of the reasons why you cannot decide a halacha based upon the Gemara, but from the Poskim who learned the Gemara and all the relevant commentaries since then. So many halachos today are simply the rabbis playing it safe, deciding like the more stringent opinion as to cover all bases. Thus is the reality of Torah as the exile deepens.

Then of course there is eilu v’eilu divrei Elokim chaim—these and these are the words of the living God. It’s when two opinions seem to contradict one another and yet are both true—to God. It’s like saying that, as much as they seem like a contradiction down here to us, higher up they work together beautifully.

As a Torah Jew, you just go with it. As a student of Kabbalah, you get used to it. Everything becomes easier to deal with once you not only acknowledge you don’t know enough to answer all the questions, you even understand how much more there is to know to answer even just most of the questions.

Once, between Mincha and Ma’ariv, I picked up the Pachad Yitzchak on Chanukah. The holiday was coming and I just felt like getting some deep insight I had never considered before. Among the few things I saw at that time, there was a ma’amer on the disagreements in Shas (all of Gemora), and what Rav Hutner, zt”l, pointed out blew me away.

Yes, we don’t like machlokes, he was basically saying. But think of all the Torah that has been brought to light because of it!

So true. All of a sudden, what I had simply attributed to something bad, the loss of Torah clarity, I saw as indirect, seemingly deliberate means for increasing Torah in the world. I don’t get them often, but that was one of those moments when you feel the beauty of an idea throughout your entire body. It didn’t just alter my perspective on machlokes, but on adversity in general.

The Torah promotes shalom bayis on all levels. It encourages the resolution of conflict, or the avoidance of it altogether. It paints a picture of a picture-perfect life, and promises one in the next world, even beginning with the Messianic Era. But God’s route to all of that is often very different than the one we imagined, even harshly different.

Even the episode with Nadav and Avihu at one of the holiest moments in human history makes this point. Human mistakes were made, but one has to wonder what God’s role was in all of this. We didn’t plan what happened and we certainly didn’t like the outcome? But did God, given the longer term plan of history?

We’ll have to wait to answer those questions, but in the meantime, each of the pieces of the puzzle, even if they don’t seem to fit together, teaches us something we need to know about life, God, and Torah. Because when it is all said and done, isn’t that the one thing we can do something about?

Tuesday, April 22, 2025

Rav Kook's Ein Ayah: Linking Liberation to Prayer; Influence of a Great Man

Linking Liberation to Prayer

(based on Ein Ayah, Berachot 1:143- part II)

Gemara: What [did Chizkiya] mean by saying: “I did that which was good in Your eyes”? Rav Yehuda said in Rav’s name: he put liberation next to prayer. Rebbi Levi said: he buried the book of medical remedies. [Last time, we discussed Rebbi Levi’s statement. When the nation is on a high level, it is better for it to exert its own efforts and see Hashem through nature. When on a low level or as the nation emerges, the nation needs to recognize Hashem through miracles. At Chizkiya’s time, it was good to bury the remedies. Now we focus on Rav Yehuda’s statement].

Ein Ayah: The idea of putting liberation right before prayer teaches us that our liberation will come only from the Hand of Hashem. It is important for us to know this because the knowledge of the great Hashem is the goal of liberation. Therefore, we should know that liberation is close to prayer and the good will from Hashem that accompanies it. When we are on a high level in service of Hashem and shleimut (completeness), liberation is close to prayer, as it truly is, even when the liberation comes through natural events and our own efforts. However, when, due to our sins, our standing is diminished and we are distanced from the shleimut of knowing Hashem, then, in our view, liberation is not near our prayers unless there are clear miracles.

Chizkiya tried to do that which is good in Hashem’s eyes. Specifically, this refers to that which brings us closer to the ethical goal, even if people do not see it as good, and that is putting liberation next to prayer. In his time, this was accomplished by making lesser efforts to succeed in a totally natural manner until he succeeded in reaching the highest level of trust in Hashem. [As we saw last time, he did not actively fight the forces of Sancheriv, who surrounded Jerusalem, but davened to Hashem to accomplish victory Himself through a miracle.] Rabbi Levi related the concept of lessening human efforts to the private realm, regarding medical needs and remedies.

Influence of a Great Man

(based on Ein Ayah, Berachot 1:145)

Gemara: “Let us make for him [the prophet, Elisha] a small attic” (Melachim II, 4:10). Rav and Shmuel disputed the matter. One said that there was an open attic and they closed it in. The other said that there was a great hall, and they broke it into two parts.

Ein Ayah: The ways of shleimut can be divided into the shleimut of the individual and helping complete the standing of another person. Regarding the complete tzaddik, it is unclear which to focus on. Is it better for him to focus on perfecting himself, and his influence on perfecting others will come by itself by means of people who are close to him? Or is it perhaps better to give up on some of his personal greatness in order to influence others for the good?

One who wants to spend a lot of time by himself will be happy to go up into an attic so that comers and goers in the house will not disturb him with too easy access to him. However, one who is interested in directly impacting others, by being close to them at the price of his own lower intensity, will chose to be in a great hall. Admittedly, within the hall there may need to be a partition so that he will have a place to which to retreat when he needs to concentrate on his own growth, but it will still be easier to mingle with him. Since so many need his guidance, he should be in a place that is nice enough to honor those who come to visit and so that they will be reminded of the grandeur of the man of G-d. All of this would be unnecessary if the point was a place for the prophet to work on himself, for which a small attic without luxuries and extras would be right.

(based on Ein Ayah, Berachot 1:143- part II)

Gemara: What [did Chizkiya] mean by saying: “I did that which was good in Your eyes”? Rav Yehuda said in Rav’s name: he put liberation next to prayer. Rebbi Levi said: he buried the book of medical remedies. [Last time, we discussed Rebbi Levi’s statement. When the nation is on a high level, it is better for it to exert its own efforts and see Hashem through nature. When on a low level or as the nation emerges, the nation needs to recognize Hashem through miracles. At Chizkiya’s time, it was good to bury the remedies. Now we focus on Rav Yehuda’s statement].

Ein Ayah: The idea of putting liberation right before prayer teaches us that our liberation will come only from the Hand of Hashem. It is important for us to know this because the knowledge of the great Hashem is the goal of liberation. Therefore, we should know that liberation is close to prayer and the good will from Hashem that accompanies it. When we are on a high level in service of Hashem and shleimut (completeness), liberation is close to prayer, as it truly is, even when the liberation comes through natural events and our own efforts. However, when, due to our sins, our standing is diminished and we are distanced from the shleimut of knowing Hashem, then, in our view, liberation is not near our prayers unless there are clear miracles.

Chizkiya tried to do that which is good in Hashem’s eyes. Specifically, this refers to that which brings us closer to the ethical goal, even if people do not see it as good, and that is putting liberation next to prayer. In his time, this was accomplished by making lesser efforts to succeed in a totally natural manner until he succeeded in reaching the highest level of trust in Hashem. [As we saw last time, he did not actively fight the forces of Sancheriv, who surrounded Jerusalem, but davened to Hashem to accomplish victory Himself through a miracle.] Rabbi Levi related the concept of lessening human efforts to the private realm, regarding medical needs and remedies.

Influence of a Great Man

(based on Ein Ayah, Berachot 1:145)

Gemara: “Let us make for him [the prophet, Elisha] a small attic” (Melachim II, 4:10). Rav and Shmuel disputed the matter. One said that there was an open attic and they closed it in. The other said that there was a great hall, and they broke it into two parts.

Ein Ayah: The ways of shleimut can be divided into the shleimut of the individual and helping complete the standing of another person. Regarding the complete tzaddik, it is unclear which to focus on. Is it better for him to focus on perfecting himself, and his influence on perfecting others will come by itself by means of people who are close to him? Or is it perhaps better to give up on some of his personal greatness in order to influence others for the good?

One who wants to spend a lot of time by himself will be happy to go up into an attic so that comers and goers in the house will not disturb him with too easy access to him. However, one who is interested in directly impacting others, by being close to them at the price of his own lower intensity, will chose to be in a great hall. Admittedly, within the hall there may need to be a partition so that he will have a place to which to retreat when he needs to concentrate on his own growth, but it will still be easier to mingle with him. Since so many need his guidance, he should be in a place that is nice enough to honor those who come to visit and so that they will be reminded of the grandeur of the man of G-d. All of this would be unnecessary if the point was a place for the prophet to work on himself, for which a small attic without luxuries and extras would be right.

Arrogance in the Service of Hashem

by HaRav Mordechai Greenberg

Nasi HaYeshiva, KeremB'Yavneh

The sons of Aharon, Nadav and Avihu, each took his fire pan, they put fire in them and placed incense upon it; and they brought before Hashem an alien fire that He had not commanded them. A fire came forth from before Hashem and consumed them, and they died before Hashem. (Vayikra 10:1-2)

Many interpretations are offered as to the sin of Aharon's sons. It seems, though, that the common denominator of them all is excessive self-pride, which is prohibited, especially for a priest who stands in service before G-d. Thus, it says in the Talmud Yerushalmi, "There is no [self-]greatness in the palace of the King." The Chovot Halevavot similarly writes (Sha'ar Hakenia ch. 6):

He should throw aside any self-glorification, haughtiness, and self-concern at the time of his service of G-d ... as the Torah writes about Aharon – despite his greatness, "He shall separate the ash." (Vayikra 6:3) G-d commanded him to take out the ash each and every day, to inculcate humility and to remove haughtiness from him. Similar to this, Scripture says about David, "leaping and dancing before Hashem." (Shmuel II 6:16)

Due to this arrogance they ruled before their teacher, sated their eyes of the Shechina, offered an alien fire, and thought that they were worthy of leading the people. [The Gemara Sanhedrin 52a and the Midrash teach that they said, "When will these two elderly people (i.e., Moshe and Aharon) die, and you and I will lead the generation." G-d said to them: "Do not boast about tomorrow."]

Ramchal (R. Moshe Chaim Luzzato) similarly writes in his work, Adir Bamarom:

He should not seek to achieve wisdom in order to reach greatness, but rather his service should be completely pure ... If not, he should be very careful, lest he ruin and not improve, and will be cast off like Acher (Elisha b. Avuya), or will be harmed like Ben Zoma. His heart should not sway him to say that G-d is yielding ... A person should not dare draw close to this great service without being called ... Rather, he should sit lowly as all other people, and should not become haughty over his brethren to raise himself to [a place] inappropriate for him, and he will receive reward for refraining just as for doing.

On a different point in the parsha, the Gerer Rebbe interpreted homiletically the Gemara in Kiddushin (30a), "The vav of gachon (belly) is the middle of the letters of the Torah." He said: A Jewish person who already learned half the Torah is liable to take credit, to pat his belly contentedly and say, "Rejoice, my insides, for I have learned much Torah." However, Chazal say, "If you learned much Torah – do not take credit, since you were created for this." (Avot 2:8) We are telling him that he should be humble, and not pat his belly, but rather he should crawl on his belly.

This same idea is said in the name of his grandfather, the Chiddushei Harim. The Gemara (Bava Batra 146a) asks on the pasuk "All the days of a poor man are bad" (Mishlei 15:15) – But there is Shabbat and Yom Tov?! The Gemara answers: "As Shmuel, who said that a change in [eating] habit is the beginning of a stomach ache." I.e., although the poor person enjoys special food on Shabbat and Yom Tov, the very change for good causes him bad later on, since his stomach is not used to it. However, the Rebbe explained as follows: The "poor" person refers to one poor in wisdom; all of his days are bad and lacking satisfaction. The Gemara asks, but on Shabbat and Yom Tov every person acquires additional da'at and rises a little from his level, and therefore he should be satisfied then! The Gemara answers that a change in habit is the beginning of a stomachache. Precisely because he feels himself elevated and more intelligent than usual, he gets a stomachache, i.e., he begins to pat his belly and to say, "Rejoice, my insides," which is, once again, something bad.

It says this it is proper to shed tears during the Torah reading about the death of Aharon's sons, and then his sins are forgiven. One who takes to heart the loss of Aharon's children, and this arouses him to repentance, is forgiven for all of his sins, "For thus said the exalted and uplifted One, Who abides forever and Whose Name is holy: I abide in exaltedness and holiness, but I am with the despondent and lowly of spirit." (Yeshaya 57:15)

Nasi HaYeshiva, KeremB'Yavneh

The sons of Aharon, Nadav and Avihu, each took his fire pan, they put fire in them and placed incense upon it; and they brought before Hashem an alien fire that He had not commanded them. A fire came forth from before Hashem and consumed them, and they died before Hashem. (Vayikra 10:1-2)

Many interpretations are offered as to the sin of Aharon's sons. It seems, though, that the common denominator of them all is excessive self-pride, which is prohibited, especially for a priest who stands in service before G-d. Thus, it says in the Talmud Yerushalmi, "There is no [self-]greatness in the palace of the King." The Chovot Halevavot similarly writes (Sha'ar Hakenia ch. 6):

He should throw aside any self-glorification, haughtiness, and self-concern at the time of his service of G-d ... as the Torah writes about Aharon – despite his greatness, "He shall separate the ash." (Vayikra 6:3) G-d commanded him to take out the ash each and every day, to inculcate humility and to remove haughtiness from him. Similar to this, Scripture says about David, "leaping and dancing before Hashem." (Shmuel II 6:16)

Due to this arrogance they ruled before their teacher, sated their eyes of the Shechina, offered an alien fire, and thought that they were worthy of leading the people. [The Gemara Sanhedrin 52a and the Midrash teach that they said, "When will these two elderly people (i.e., Moshe and Aharon) die, and you and I will lead the generation." G-d said to them: "Do not boast about tomorrow."]

Ramchal (R. Moshe Chaim Luzzato) similarly writes in his work, Adir Bamarom:

He should not seek to achieve wisdom in order to reach greatness, but rather his service should be completely pure ... If not, he should be very careful, lest he ruin and not improve, and will be cast off like Acher (Elisha b. Avuya), or will be harmed like Ben Zoma. His heart should not sway him to say that G-d is yielding ... A person should not dare draw close to this great service without being called ... Rather, he should sit lowly as all other people, and should not become haughty over his brethren to raise himself to [a place] inappropriate for him, and he will receive reward for refraining just as for doing.