(Editor's note: I usually rerun this drasha each year because it shows that without Rav Kook, there would have been no B'nei Brak)

Moshe's rage was palpable. “You have risen in your fathers’ places as a band of sinners!” (Bamidbar 32:14).

When the tribes of Gad and Reuven petitioned not to cross the Jordan River and enter Israel proper, Moshe denounced the proposition and lashed out at them. “Why are you trying to discourage the Israelites from crossing over to the Land that God has given them?”

We can certainly understand Moshe's anger and frustration. But this incident took place not long after he was punished for berating the people at Mei Merivah. When he snapped at the people, “Listen now, you rebels!” (Bamidbar 19:10), God informed Moshe that he would not be leading the Jewish people into the Land of Israel.

We similarly find that the prophet Yishayahu was punished for his harsh criticism when he lamented, “I live among a people of unclean lips” (6:5).

Yet there is no indication that Moshe was wrong in his scathing response to the tribes of Gad and Reuven. What was different?

Imitating the Mistake of the Spies

Rav Kook explained that, in this situation, Moshe was justified in his outrage. Moshe realized that their request could discourage the entire people from entering the Land, like the debacle of the Spies. His response needed to be stern.

We learn from here that anyone discouraging the Jewish people from ascending to the Land is following in the footsteps of the infamous Spies and repeating their disastrous folly.

The tribes of Gad and Reuven presented reasonable arguments — “we have much livestock.” But their request could erode the people’s commitment to settle the Land. There was no place for polite discussion; Moshe needed to be forceful and resolute. And if that was true for the righteous tribes in the time of Moshe, what can we say in our generation, even when people offer what appear to be reasonable objections to making Aliyah?

Rav Kook concluded: we are unable to fathom God’s ways, but nothing exempts one from Aliyah to Eretz Yisrael. We must bolster our faith that, by ascending to the Land and settling it, we are fulfilling the Torah’s goals.1

Rav Kook’s forceful words found a practical application in an unusual court case that he adjudicated in 5682 (1922).

Warsaw, 1920.

Yitzchak Gershtenkorn had a plan. A brilliant, magnificent plan. The 29-year-old Hassidic Jew from Warsaw approached two friends with his proposal: every week, they would deposit money into a joint bank account. The funds would be dedicated to a single goal — to purchase land to settle in Eretz Yisrael.

His friends enthusiastically agreed. Over the coming months, they deposited money each week, excited in the knowledge that each payment brought them a little closer to their goal.

Yitzchak Gershtenkorn had a plan. A brilliant, magnificent plan. The 29-year-old Hassidic Jew from Warsaw approached two friends with his proposal: every week, they would deposit money into a joint bank account. The funds would be dedicated to a single goal — to purchase land to settle in Eretz Yisrael.

His friends enthusiastically agreed. Over the coming months, they deposited money each week, excited in the knowledge that each payment brought them a little closer to their goal.

R. Yitzchak noted that his endeavor was already a remarkable success. His two friends, who had never dreamed of settling the Land, had changed. They acquired new aspirations; their views on Galut (exile) and the Land of Israel had shifted. They had become “Jews of Eretz Yisrael”!

He decided the time was right to take the next step. He began recruiting other religious Jews in Warsaw. Gershtenkorn spoke in synagogues about settling and working the Land, raising great interest. Within a short time, the group numbered 150 members. They formed a society called Bayit VeNachalah (“Home and Heritage”), dedicated to establishing an agricultural community for religious settlers in the Holy Land.

After the initial enthusiasm, however, the project began to waver. Some members were nervous because Polish law prohibited taking money out of the country. Others worried that the funds raised were so meager that, even after years of saving, they would not suffice to purchase suitable land in Eretz Yisrael. Several members threatened to resign.

That winter, the Gerrer Rebbe returned from a visit to Eretz Yisrael.2

After the initial enthusiasm, however, the project began to waver. Some members were nervous because Polish law prohibited taking money out of the country. Others worried that the funds raised were so meager that, even after years of saving, they would not suffice to purchase suitable land in Eretz Yisrael. Several members threatened to resign.

That winter, the Gerrer Rebbe returned from a visit to Eretz Yisrael.2

The Rebbe granted an audience to R. Yitzchak and told him,

“I will recommend anyone who asks me that they should join your group. I cannot provide you with any financial help because I am already committed to a similar undertaking in the Jaffa area. But never get discouraged! God will crown your venture with success.”

Encouraged, R. Yitzchak called a general meeting of Bayit VeNachalah. When the members heard the Gerrer Rebbe’s words and blessing, their doubts and hesitations were dispelled.

Purchasing Bnei Brak

Two years later, R. Yitzchak and two other delegates traveled to EretzYisrael to locate a suitable plot of land for their envisioned community. In his memoirs, R. Yitzchak described his high emotions during the long train ride from Egypt to the Holy Land:

“On that night, as we traveled from Alexandria to Tel Aviv, I could not sleep. We passed through the desert, and the sand penetrated our railway carriage through the closed blinds. To me it was symbolic: a person does not enter the Land of Israel unless he is first covered in desert sand, like our ancestors long ago who sojourned through the Sinai desert.

Absorbed in my thoughts, the sights and visions of Biblical times passed before my eyes. In my mind, I saw the journeys of the ancient Israelites, traveling with their flags and tribal camps. I, too, was not traveling alone, but stood at the head of an entire camp of Warsaw Jews, who were waiting to hear the results of our expedition.

My heart began to beat fast. We are crossing the border! We are already traveling in our Land. I opened the window wide and breathed in the soul-reviving air of Eretz Yisrael.”

While the purpose of the journey was to locate a suitable plot of land, R. Yitzchak took advantage of times between trips to meet the prominent scholars and rabbis of the holy city of Jerusalem. On the Shabbat before Passover, he visited Rav Kook in his home, where he was greeted with great warmth.3

For three weeks, the delegates searched for suitable land, examining plots near Rehovot and Rishon LeTzion. But Gershtenkorn was most drawn to a hilly stretch of ground along the road from Tel Aviv to Petach Tikva. The land belonged to a few Arab families who lived in a nearby village.

The residents of the nearby settlements urged them to buy this particular piece of land so that all Arab holdings from northern Tel Aviv to Petach Tikva would be under Jewish ownership. It was a matter of security; the hills of Bnei Brak were used by Arabs to ambush Jewish travelers. A new Jewish settlement would dislodge the Arab raiders and secure the road from Tel Aviv to the Sharon region.

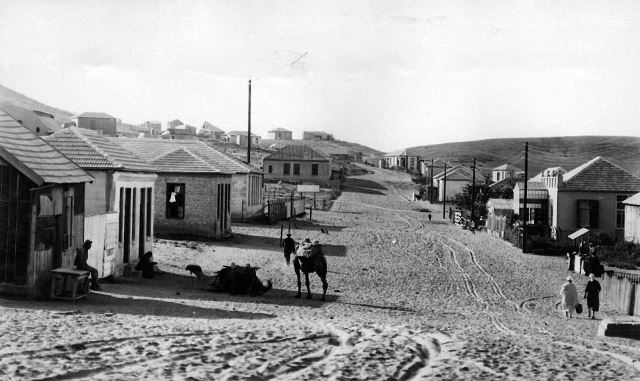

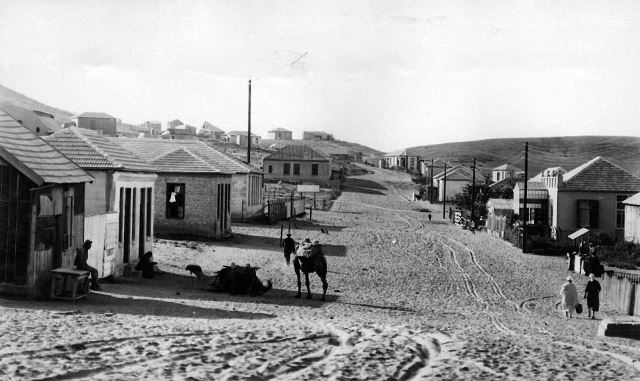

The main street of Bnei Brak, 1928

The main street of Bnei Brak, 1928

“I will recommend anyone who asks me that they should join your group. I cannot provide you with any financial help because I am already committed to a similar undertaking in the Jaffa area. But never get discouraged! God will crown your venture with success.”

Encouraged, R. Yitzchak called a general meeting of Bayit VeNachalah. When the members heard the Gerrer Rebbe’s words and blessing, their doubts and hesitations were dispelled.

Purchasing Bnei Brak

Two years later, R. Yitzchak and two other delegates traveled to EretzYisrael to locate a suitable plot of land for their envisioned community. In his memoirs, R. Yitzchak described his high emotions during the long train ride from Egypt to the Holy Land:

“On that night, as we traveled from Alexandria to Tel Aviv, I could not sleep. We passed through the desert, and the sand penetrated our railway carriage through the closed blinds. To me it was symbolic: a person does not enter the Land of Israel unless he is first covered in desert sand, like our ancestors long ago who sojourned through the Sinai desert.

Absorbed in my thoughts, the sights and visions of Biblical times passed before my eyes. In my mind, I saw the journeys of the ancient Israelites, traveling with their flags and tribal camps. I, too, was not traveling alone, but stood at the head of an entire camp of Warsaw Jews, who were waiting to hear the results of our expedition.

My heart began to beat fast. We are crossing the border! We are already traveling in our Land. I opened the window wide and breathed in the soul-reviving air of Eretz Yisrael.”

While the purpose of the journey was to locate a suitable plot of land, R. Yitzchak took advantage of times between trips to meet the prominent scholars and rabbis of the holy city of Jerusalem. On the Shabbat before Passover, he visited Rav Kook in his home, where he was greeted with great warmth.3

For three weeks, the delegates searched for suitable land, examining plots near Rehovot and Rishon LeTzion. But Gershtenkorn was most drawn to a hilly stretch of ground along the road from Tel Aviv to Petach Tikva. The land belonged to a few Arab families who lived in a nearby village.

The residents of the nearby settlements urged them to buy this particular piece of land so that all Arab holdings from northern Tel Aviv to Petach Tikva would be under Jewish ownership. It was a matter of security; the hills of Bnei Brak were used by Arabs to ambush Jewish travelers. A new Jewish settlement would dislodge the Arab raiders and secure the road from Tel Aviv to the Sharon region.

The main street of Bnei Brak, 1928

The main street of Bnei Brak, 1928Rav Kook’s Ruling

There was, however, a serious issue which led to a vehement dispute among the delegates. Geulah, the organization responsible for redeeming land from Arab hands, requested 10,000 pounds sterling for the property they sought. But their society had only collected 900 pounds.

The other delegates were wary. How could they obligate themselves to an additional sum of 9,000 pounds — ten times more than they had succeeded in saving at that point! — without prior consensus of the entire group?

Gershtenkorn was confident that the money could be raised. After many arguments, the delegates agreed to bring the matter as a Din Torah for the Chief Rabbi, Rav Kook. According to his decision, they would proceed.

The evening after Passover, the delegates presented their dispute to Rav Kook. The society’s treasurer argued that he saw no basis at the current time for a reasonable livelihood for the members, who are not wealthy; it is the delegates’ obligation to be faithful agents and not conclude any transaction until returning to Warsaw and giving an accurate report to the society.

Yitzchak Gershtenkorn argued that he was the sole official representative; the other delegates had no right to obstruct the purchase.

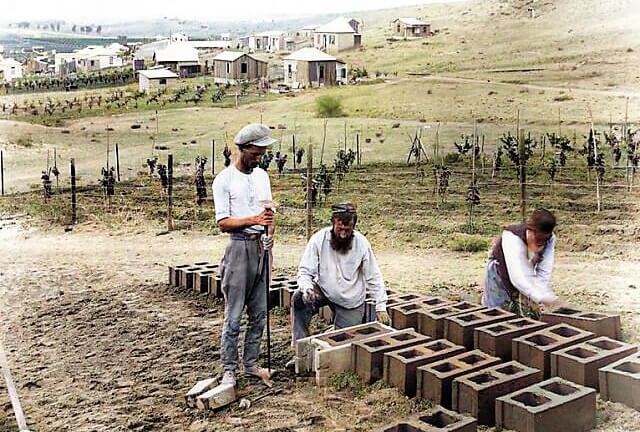

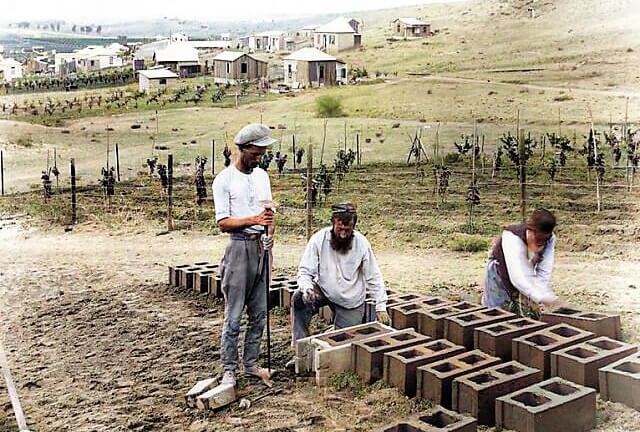

Making blocks to build houses. Bnei Brak, 1928

Making blocks to build houses. Bnei Brak, 1928

There was, however, a serious issue which led to a vehement dispute among the delegates. Geulah, the organization responsible for redeeming land from Arab hands, requested 10,000 pounds sterling for the property they sought. But their society had only collected 900 pounds.

The other delegates were wary. How could they obligate themselves to an additional sum of 9,000 pounds — ten times more than they had succeeded in saving at that point! — without prior consensus of the entire group?

Gershtenkorn was confident that the money could be raised. After many arguments, the delegates agreed to bring the matter as a Din Torah for the Chief Rabbi, Rav Kook. According to his decision, they would proceed.

The evening after Passover, the delegates presented their dispute to Rav Kook. The society’s treasurer argued that he saw no basis at the current time for a reasonable livelihood for the members, who are not wealthy; it is the delegates’ obligation to be faithful agents and not conclude any transaction until returning to Warsaw and giving an accurate report to the society.

Yitzchak Gershtenkorn argued that he was the sole official representative; the other delegates had no right to obstruct the purchase.

Making blocks to build houses. Bnei Brak, 1928

Making blocks to build houses. Bnei Brak, 1928After much deliberation, Rav Kook ruled in favor of Gershtenkorn. He noted three points:

1. We must distinguish between an individual and a community. If an individual asks whether he should make Aliyah or not, one is permitted to give advice for a specific case. But a community is a different story. One who influences the views of an entire community and deters them from moving to the Land — he is “giving an evil report of the Land” and repeating the villainous act of the Spies.

2. Regarding the concerns that the group will be unable to complete the purchase of the land, we have a rule in Halachah that “The community is not poor.” Who said that only the current members will foot the bill? If they are unable to pay, other Jews of means will come and purchase a share, thus enabling the society to conclude the land acquisition.

3. Yitzchak Gershtenkorn was appointed as the sole representative with powers to purchase. The other delegates did not have the right to prevent him from executing the transaction.

Two weeks later, R. Yitzchak handed over the society’s money as down-payment for the land. Thus the agricultural settlement of Bnei Brak was founded — on the 5th of Iyyar.4

(Adapted from Mo'adei HaRe’iyah, pp. 405-407. Chaluztim LeTzion: the Founding of Bnei Brak with Rav Kook’s Support, by Moshe Nachman, pp. 32-33. Background details from The Jewish Observer, Sept. 1974)

__________________________________________________________________________________

1. We must distinguish between an individual and a community. If an individual asks whether he should make Aliyah or not, one is permitted to give advice for a specific case. But a community is a different story. One who influences the views of an entire community and deters them from moving to the Land — he is “giving an evil report of the Land” and repeating the villainous act of the Spies.

2. Regarding the concerns that the group will be unable to complete the purchase of the land, we have a rule in Halachah that “The community is not poor.” Who said that only the current members will foot the bill? If they are unable to pay, other Jews of means will come and purchase a share, thus enabling the society to conclude the land acquisition.

3. Yitzchak Gershtenkorn was appointed as the sole representative with powers to purchase. The other delegates did not have the right to prevent him from executing the transaction.

Two weeks later, R. Yitzchak handed over the society’s money as down-payment for the land. Thus the agricultural settlement of Bnei Brak was founded — on the 5th of Iyyar.4

(Adapted from Mo'adei HaRe’iyah, pp. 405-407. Chaluztim LeTzion: the Founding of Bnei Brak with Rav Kook’s Support, by Moshe Nachman, pp. 32-33. Background details from The Jewish Observer, Sept. 1974)

__________________________________________________________________________________

1 According to Shivchei HaRe’iyah, p. 268, Rav Kook related this idea to Ravbbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn (1880-1950), the sixth Rebbe of Lubavitch, when the Rebbe visited Rav Kook in 1929. The Rebbe is reported to have responded, “These are holy words from a holy mouth.”

2 Rav Avraham Mordechai Alter (1866-1948), known as the Imrei Emet of Gur, had a special love for Eretz Yisrael. He visited four times, purchased parcels of land, and urged his chassidim to do likewise. The fifth time he came to Israel, it wasn’t as a visitor. He was fleeing from occupied Poland and the Nazis, who placed the “Wunder Rebbe Alter” at the top of their most-wanted list. Elderly and in ill health, the Rebbe escaped from Poland in 1940 to the house that awaited him in Jerusalem. (Mishpacha Magazine, Sep. 2018)

3 In his memoirs, Yitzchak Gershtenkorn described his surprise upon meeting Rav Kook:

“In Poland at that time, one had the impression that there were two chief rabbis in Jerusalem. The first was Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, appointed by the Haredi community; and the second was the leader of the enlightened community — Rav Avraham Isaac Kook. I pictured Rav Kook as a modern rabbi. A year before my visit, I had become friendly with his son, Rav Tzvi Yehuda Kook [who visited Warsaw to promote his father’s movement, Degel Yerushalayim]. Already in Warsaw, R. Tzvi Yehuda made a deep impression on me as a serious Torah scholar, distinguished in Torah and piety. But the Haredi newspapers in Poland would always stress the prominence and authority of those who opposed Rav Kook.

How great was my astonishment during my first visit to Rav Kook’s house. I saw before me a holy tzaddik, one of the select few of the generation. How saintly and noble was his holy visage! ... His words of Torah and piety flowed like a spring, brimming with love for the Land of Israel and the Jewish people... After that visit, I become attached to Rav Kook in heart and soul.”

4 The following week, Gershtenkorn met with Rav Kook before returning to Poland. Rav Kook provided him with a public letter of recommendation to help enlist more members and financial support. R. Yitzchak wrote in his memoirs:

“At all times, the Gaon [Rav Kook] was my faithful light and guide in our dealings regarding Bnei Brak. During the most trying and difficult days, when I would travel to Jerusalem to pour out my heart and soul before the Kotel, I never missed the opportunity to visit his holy abode. The encouragement and strength that I received from him were a balm for my soul.”

Rav Kook posing with the founders of Bnei Brak. Standing to the right is Yitzchak Gershtenkorn

No comments:

Post a Comment