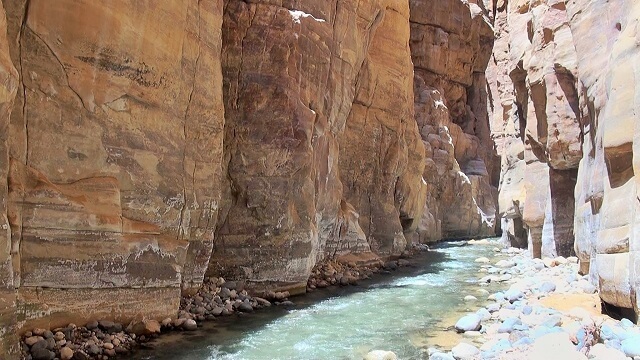

Just before the Israelites were to enter the Land of Israel, the Amorites (one of the Canaanite nations) laid a trap for them. They chipped away at the rock, creating hiding places along a narrow pass in the Arnon canyon. There the Amorite soldiers hid, waiting for the Israelites to pass through, when they could attack them with great advantage.

What the Amorites didn’t know was that the Holy Ark would smooth the way for the Jewish people in their travels through the desert. When the Ark arrived at the Arnon Pass, the mountains on each side crushed together, killing the Amorite soldiers. The Israelites traveled through the pass, blissfully unaware of their deliverance. But at the end of the Jewish camp were two lepers, named Et and Vehav. The last ones to cross through, it was they who noticed the riverbed turned crimson from the crushed enemy soldiers. They realized that a miracle had taken place, and reported it to the rest of the Israelites. The entire nation sang a song of thanks, namely, the poetic verses that the Torah quotes from the “Book of God’s Wars.”

Challenges to the Torah

The Talmud clearly understands that this was a historical event, and even prescribes a blessing to be recited upon seeing the Arnon Pass. Rav Kook, however, interpreted the story in an allegorical fashion. What are “God’s Wars”? These are the ideological battles of the Torah against paganism and other nefarious views. Sometimes the battle is out in the open, a clear conflict between opposing cultures and lifestyles. And sometimes the danger lurks in crevices, waiting for the opportune moment to emerge and attack the foundations of the Torah.

Often it is precisely those who are on the fringes, like the lepers at the edge of the camp, who are most aware of the philosophical and ideological battles that the Torah wages. These two lepers represent two types of conflict between the Torah and foreign cultures. And the Holy Ark, containing the two stone tablets from Sinai, is a metaphor for the Torah itself.

The names of the two lepers were Et and Vahav. What do these peculiar names mean?

The word Et in Hebrew is an auxiliary word, with no meaning of its own. However, it contains the first and last letters of the word emet, ‘truth.’ Etrepresents those challenges that stem from new ideas in science and knowledge. Et is related to absolute truth; but without the middle letter, it is only auxiliary to the truth, lacking its substance.

The word Vahav comes from the work ahava, meaning ‘love’ (its Hebrew letters have the same numerical value). The mixing up of the letters indicates that this an uncontrolled form of love and passion. Vahav represents the struggle between the Torah and wild, unbridled living, the contest between instant gratification and eternal values.

When these two adversaries — new scientific viewpoints (Et) and unrestrained hedonism (Vahav) — come together, we find ourselves trapped with no escape, like the Israelites in the Arnon Pass. Only the light of the Torah (as represented by the Ark) can illuminate the way, crushing the mountains together and defeating the hidden foes. These enemies may be unnoticed by those immersed in the inner sanctum of Torah. But those at the edge, whose connection to Torah and the Jewish people is tenuous and superficial, are acutely aware of these struggles, and more likely to witness the victory of the Torah.

The crushing of the hidden adversaries by the Ark, as the Israelites entered into the Land of Israel in the time of Moshe, is a sign for the future victory of the Torah over its ideological and cultural adversaries in the time of the return to Zion in our days.

(Gold from the Land of Israel, pp. 266-267; adapted from Ein Eyah vol. II, p. 246 by Rav Chanan Morrison)

No comments:

Post a Comment