“How intense, how grave, how dire were the warnings and intimidations at that time, with all of their menacing threats. Two nations [the Arabs and the British] were goading us with lies and murderous traps, to sign an agreement and relinquish [Jewish] ownership over the Kotel, the remaining wall of our Holy Temple...” (LeNetivot Yisrael vol. I, p. 65)

The Mufti’s Ambitions

Already in the time of the first British High Commissioner, Hajj Amin al-Husseini was appointed Mufti of Jerusalem, spiritual and national leader of the Arabs. One of the many devices that the infamous mufti employed in his fight against the Jewish national return to Eretz Yisrael was to repudiate all Jewish rights to the Kotel HaMa’aravi, the Western Wall.

The Arabs gained a partial victory in 1922, when the British Mandatory Government issued a ban against placing benches near the Kotel. In 1928, British officers interrupted the Yom Kippur service and forcibly dismantled the mechitzah separating men and women during prayer.

A few months later, the Mufti and his cohorts devised a new provocation. They began holding Muslim religious ceremonies opposite the Kotel, precisely when the Jews were praying. To make matters worse, the British authorities granted the Arabs permission to transform the building adjacent to the Kotel into a mosque, complete with a tower for the muezzin, the crier calling Moslems to prayer five times a day. The muezzin’s vociferous trills were certain to disturb the Jewish prayers.

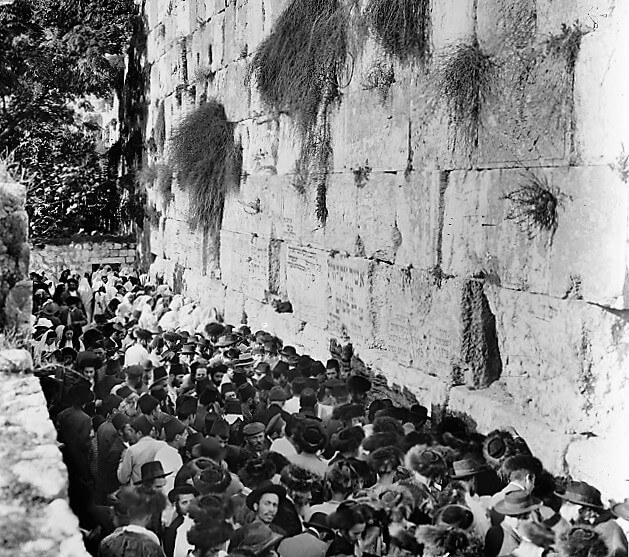

Active Arab turbulence reached its peak during the bloody riots of 1929. On the 10th of Av, some 2,000 Arabs swarmed the Kotel, chasing away the Jews praying there and burning several Torah scrolls. The following week, rioting broke out in Jerusalem and spread throughout the country. Nearly a hundred Jews were slaughtered in the riots, mainly in Hebron and Jerusalem.

Rav Kook and the Kotel Commission

In the summer of 1930, the League of Nations dispatched a committee to Eretz Yisrael to clarify the ownership of the Western Wall. The Arabs claimed to be the rightful owners, not only of the Temple Mount but of the Kotel as well. They rejected any agreement that permitted Jews to pray at the Kotel. It is solely a Muslim site, the Mufti claimed; the Jews may pray at the Kotel only by the good grace of the Arabs.

When Rav Kook appeared before the Commission, he turned to the chairman with deep emotion:

“What do you mean when you say, ‘The Commission will decide to whom the Wall belongs’? Does this commission or the League of Nations own the Wall? Who gave you permission to decide to whom it belongs? The entire world belongs to the Creator, blessed be He; and He transferred ownership of the entire Land of Israel — including the Kotel — to the Jewish people [Rashi on Bereisheet 1:1]. No power in the world, not the League of Nations, nor this commission, can take this God-given right away from us.”

The chairman retorted that the Jews have not been in control of the Land of Israel or the Wall for close to two thousand years. At this point, Rav Kook decided the members of the commission needed to learn a lesson in Jewish law. Calmly and respectfully, he explained:

“In Jewish law, the concept of yei'ush be'alim ['owner’s despair'] applies also to real estate. [That is, the owner of a stolen tract of land forfeits his ownership if he gives up hope of ever retrieving it.] However, if a person’s land is stolen and he continuously protests the theft, the owner retains his ownership for all time.” 1

Rav Kook’s proud appearance before the commission made a powerful impact on the Jewish community. The Hator newspaper commented:

“We cannot refrain from mentioning once again the Chief Rabbi of EretzYisrael, who sanctified God and Israel with his testimony. The witnesses who preceded him stood meekly, with tottering knees. After the Chief Rabbi’s appearance, we felt a bit relieved, as if a weight had been lifted from our hearts. He raised our heads, straightened our backbones, and restored dignity to the Torah and our nation.”

The Proposal of the Va’ad Leumi

The British Mandatory government suggested a compromise according to which the Jews would recognize Arab ownership of the Kotel, and the Arabs in return would permit Jews to approach the Wall. (The right for Jews to pray at the Kotel was not explicitly mentioned.)

Due to the tense political situation — particularly in light of the murderous Arab rioting the previous year — the Va’ad Leumi (the executive committee of the Jewish National Assembly in pre-state Israel) was prepared to recognize Arab ownership of the Kotel. However, the Va’ad Leumi stipulated that the Arabs must explicitly recognize the right of Jews to pray there.

Because this was a religious matter, the Mandatory government required that the Va’ad Leumi’s proposal be approved by the religious authority of the Jews, namely, the rabbinate. In order to apply greater pressure on the rabbis, the Va’ad Leumi sent delegations simultaneously to the two chief rabbis, Rav Kook and Rabbi Yaakov Meir, as well as to Rabbi Zonnenfeld, representing Agudat Israel.

A delegation from the Va’ad, headed by Yitzchak Ben-Zvi, visited Rav Kook and tried to persuade him to approve the plan. It is a matter of life and death, they argued; only by renouncing Jewish ownership will we assuage the Arabs and bring peace to Israel.

Rav Kook’s Response

Despite intense pressure from the Va’ad Leumi, Rav Kook refused to authorize the proposal.

“We have no authority to do such a thing. The Jewish people did not empower us to surrender the Western Wall on its behalf. Our ownership over the Kotel is Divine in nature, and it is by virtue of this ownership that we come to pray at the Kotel.

I cannot relinquish that which God gave to the Jewish people. If, Heaven forbid, we surrender the Kotel, God will not wish to return it to us!”

As it turned out, the Arabs refused even to consider granting the right of Jewish prayer at the Kotel, and the proposal died. Indeed, after the War of Independence, although the cease-fire agreement provided for the right of Jews to approach the Kotel, the Arabs ignored this provision. Only nineteen years later, when God restored the Kotel to its rightful owners in the Six-Day War, did the Jewish people merit once again to pray unhindered at the Western Wall.

Addendum

R. Menachem Porush, chairman of Agudat Israel, contributed the following detail of this incident:

Rav Kook, upon receiving the proposal, stated that he would not agree to relinquish the Jewish claim to the Kotel under any circumstances. He also dispatched a personal messenger to Rav Zonnenfeld to inform him of his refusal, and to beg him not to show the British any lack of determination in the matter.

Rav Zonnenfeld, when he received notice of the proposal, also refused to agree. Afraid that Rav Kook might not be firm enough in refusing the proposal, Rabbi Zonnenfeld dispatched his own messenger to Rav Kook to inform him of his policy and to request that he not show any willingness to compromise on the matter.

The two messengers, who happened to be personal friends, met in the street and discussed their missions and messages. Both were relieved when they realized that there was no need to deliver their respective messages. Thus, the plan, which would have compromised Jewish rights to the Kotel for generations, died aborning.

(Stories from the Land of Israel. Adapted from Celebration of the Soul, p. 244; An Angel Among Men, pp. 206-207,215-217,219; R. Porush’s letter, quoted by Rav Dov Berel Wein.)

No comments:

Post a Comment