by Rav Binny Freedman

Sometimes, it’s that one extra word that makes all the difference. It was only a fraction of a moment of my time in the army, but it was a lesson I never forgot, though to this day I am undecided as to whether I agree with it.

I was desperate to get a day off; we were still in basic training, and I had barely been in the army three months, but my folks were landing at the airport the next afternoon, and I was hoping my commanders would give me a break as I had not seen head or hair of any family in the two months since I had joined up.

My folks had done me the enormous favor of landing on a Thursday afternoon, which was the best possible day of the week for a tank crewman to get extra leave. Thursday was “Tipul She’vui” day, which meant the weekly servicing and cleaning of every last inch of every tank, top to bottom. In the Israeli army, there are no special maintenance crews that tag along to service the tanks with regular maintenance; unlike the American army, Israeli soldiers have to do it all on their own, and that means getting down and dirty with all the grease and grime, not to mention the endless inspections. Tank crews, often after a week of long maneuvers and little sleep, can usually be found working on their tanks into the wee hours of the morning to prepare for the infamous Friday morning inspections.

Add to that the fact that my unit was meant to get out for Shabbat (Friday morning after inspection), and special leave on Thursday would mean a pass all the way till Sunday, and I was desperate to get the day off.

Which was why I was standing at attention in the glaring sun, waiting for my sergeant to return with the answer to my properly formatted request (by way of the sergeant, to the platoon officer), for a special day’s leave.

I was afraid to dream in case I would be disappointed, yet I couldn’t help myself; visions of a hot bath, a night out on the town, and a real bed with clean sheets swam before my eyes.

The sergeant came out of the command tent a few minutes later, and I was shocked to see he actually had a smile on his face, I had never seen the muscles in his jaw work that way before, and then the one word I had been waiting for:

“Be’seder”, “O.K.”

“Be in your dress uniform at 08:00 hours, and your extra day’s leave is granted.’

I couldn’t help myself; a huge grin spread across my face, and I felt like dancing, and then that one terrible word escaped, the one I still remember:

“Todah.” “Thank you, sir.”

I could tell I was in trouble as soon as the words left my lips, his eyes changed first, then his entire face, and then the glare we all feared, the one that meant you were about to get a serious work-out.

“Mah Zeh?” “What’s that?”

Although I did end up getting out, albeit a good few hours later than I had hoped, I never worked so hard for a pass in my life. You see, in the army, you don’t say thank you.

After running around the base seven times singing “Lo’ Omrim Todah”, “Todah Al Kol Mah’ She’Barata’, and every other song with the word Todah (Thank you) in it that I could think of, they finally let me go, but the message would stay with me forever.

The army, I learned, is about orders and commands. There is no ‘thank you’ and no ‘you’re welcome’; you do what is expected of you because that’s your job.

Thank you implies the possibility you didn’t have to do what it was you were doing, and that you deserve to be thanked for going ahead and doing it anyway. In the army, however, you are always fulfilling orders, and no one would ever expect any less than total compliance, and complete obedience.

You don’t thank your kids for brushing their teeth in the morning, and your children don’t thank you for coming home at the end of the day; it’s just what you do, and who you are, and they would expect no less.

And yet, something has always bothered me about this approach, which never worked for me as a commander.

This week’s portion, Pekudei, is a case in point:

“And all the work of the Mishkan, the Tent of Meeting, was completed, and the children of Israel did all that Hashem had commanded them, so they did (“Ken Asu'”).” (Shemot 39:32)

Why does the Torah have to tell me that the Jewish people did everything that Hashem commanded them to do? Of course, they did! If G-d commanded you to do something, wouldn’t you do it? And note that the verse repeats itself, stressing the fact that they did all that was demanded of them; why is this worthy of mention? Should we have expected anything less?

As if this is not enough, the Torah does not stop there:

“And all that Hashem commanded Moshe, so did the children of Israel do: all of the labor.” (39:42)

Again, the Torah stresses that the Jewish people did it all, which seems redundant. Why is this so important? And then the Torah goes a stage further:

” And Moshe saw all the labor, and behold they did it just as Hashem had commanded, so did they do it, and Moshe blessed them.” (39: 43)

Why, now, all of a sudden does Moshe bless them?

What is the nature of this blessing? Is Moshe thanking them? Since when does Moshe say thank you to the Jewish people for doing what Hashem has asked of them?

Further, why are the Jewish people commanded to build the Mishkan in the first place? The Mishkan was for man’s benefit, not G-d’s. So why are the Jews blessed for fulfilling what was essentially a project for their own benefit? (Either as an opportunity to atone for, or at least somehow rectify the mistake of the Golden Calf, or as a vehicle to develop a more tangible relationship with G-d and create a more meaningful life.)

It would seem the Jewish people should be thanking G- d, and certainly not the other way around! So why is Moshe saying thank you here? And even if this blessing is of a different nature, what need is there for Moshe to offer any comment at all? The people did what was expected of them, end of story! What message is Moshe imparting to us here?

Additionally, it is interesting to note that verse 32 here seems to be out of order.

“And all the work of the Mishkan - the Tent of Meeting, was completed, and the children of Israel did all that Hashem had commanded them, so they did.”

Why does the verse tell me the work was completed and only then tell me the Jewish people did all they were commanded to do? Wouldn’t it make more sense to say that the Jews did all the work they were commanded to do, and thus, the Tabernacle was completed? Why the reverse and more challenging order in this verse?

And if we are discussing the accolades the Jewish people receive for having built the Mishkan exactly according to the specifications, we must also ask: who really built this tabernacle? Did all of the Jewish people lend a hand in the building? The idea that 600,000 men between the ages of twenty and sixty (army age) all got together and participated in this building project makes no sense whatsoever. It is hard enough to get two or three Jews together on a project; can you imagine trying to organize six hundred thousand?

Indeed, the verses are very clear about who actually built the Mishkan: the Chochmei Lev, the artisans under Betzalel and Ohaliav, built it. (See 36:2-4; 8) So why is the entire nation thanked for getting the job done down to the last detail?

It is interesting to note that this entire portion begins with unusual attention to detail; indeed, these are the opening words of the portion, from whence it derives its name:

“Eleh’ Pekudei HaMishkan..” Literally: “These are the accountings of the Mishkan..” (38:21)

Now that the Mishkan has been completed, the Torah gives us what is essentially a treasurer’s report of the collections tally; an accounting of all the income and outlay, and a list of all of the items produced in the making of the Mishkan, down to the last detail. Why is there a need to devote an entire portion to such a detailed list? The Torah is meant to be a recipe for living and a guide to life. Why must we be privy to how many sockets and posts were made, and how much gold and silver was used in the construction?

Many of the commentaries speak of the ethical implications here, and of the need for public servants to be accountable, but is there perhaps a deeper principle at the root of this three-thousand-year-old Excel spread sheet?

Lastly, the end of the portion, which usually relates to the theme and the purpose of all the ideas contained in the entire portion, also requires some explanation.

Recall that this week’s portion is also the concluding portion of the entire book of Shemot. As a rule, when studying a particular portion, the beginning and end of that portion allude to the theme of the entire portion; how the Torah chooses to begin and end a section, speaks volumes about the theme and goals of that section.

The end of this week’s parsha (portion) then, is rather critical towards understanding the theme, and indeed the point, of the entire book of Shemot.

Which makes the end of this book rather puzzling. The Torah tells us (40:34-38) that a cloud covered the tent of meeting, and “the glory of G-d filled the tent.” (Verse 34) And once the glory of G-d filled the Tent, Moshe could not enter it (verse 35). And this cloud, which seems somehow to be representative of the glory (honor?) of G-d, was also, the Torah tells me, the indicator for the Jewish people as to whether they should set forth or make camp. The Jewish people, we are told, in making their travel plans, do not depend on the weather, and they do not travel based on provisions. They watch the clouds of glory, and G-d’s self tells them when and for that matter, where to go.

Why is this the conclusion to the entire book of Exodus? And why is it apparently so important that Moshe could no longer enter the tent of meeting? And what does all this have to do with the issues discussed above?

This portion is clearly about the details, not just the significance of every single detail, but the value of seeing every detail as part of a larger picture.

The Netziv (Rav Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin), the Rosh Yeshiva of Volozhin in the mid-nineteenth century), points out in his Ha’Emek Davar (39:42) that the tendency of most people in pursuit of great dreams, is to go far beyond the tasks at hand, and people tend to get so ‘carried away’ by the process, that they forget what the purpose was in the first place.

Indeed, the prelude to this challenge is already to be found in last week’s portion Va’Yakhel. The people were so excited at the prospect of building the Mishkan, and perhaps so moved by the opportunity to atone for their mistake in building a golden calf, that they could not donate enough goods for the Mishkan. Every morning the piles of material grew at an astounding rate (36:3) until the artisans responsible for the execution of the project could not keep up with the influx of material.

“And they said to Moshe, saying: the people are bringing too much, there is more material than is necessary for the work Hashem has commanded (us) to do.” (36:4)

Can you imagine? There are too many donations! Every Rabbi’s dream: the dinner was so successful there is too much money, and the people keep bringing more!

But still more incredible is Moshe’s response:

“And Moshe commanded and the word was spread throughout the camp saying: let every man and woman do no more work for the donation to the holy, and the people ceased bringing.” (36:6)

Moshe actually tells the people to stop bringing goods to donate to the tabernacle! Why? Why not just keep collecting the money, and put it away for a rainy day? What could possibly be wrong with the people continuing in the pursuit of what was obviously a very important mitzvah?

Perhaps what was really at the root of this dialogue was not what the people were bringing, but rather how they were bringing it.

Sometimes, we get so involved in the process; we forget what it is really all about.

I recall once having been invited to a bar mitzvah, which turned out to be a very lavish affair. The party took place on a Saturday night, and when I arrived it looked more like a wedding than a bar mitzvah, and it seemed very obvious that the guests of honor were indeed the bride and groom, who in this case were the parents of the Bar Mitzvah boy.

There were over four hundred people at this affair, magnificent tables, a band, lavish food, and the only thing missing was the bar mitzvah boy. Wanting to wish him a mazal tov, I finally found him with his friends in a separate room where he and his friends were having their own separate party, complete with dinner and games, Viennese desserts, video technology, a movie they were watching on a large screen, and of course. a cart full of presents which would eventually be wheeled out and opened as the central piece of their evening. It seemed there was plenty of ‘bar’, but very little ‘mitzvah’.

Sometimes, we lose sight of the purpose of what we are doing and allow ourselves to get caught up in the process of accomplishing it. Perhaps what was troubling Moshe and the artisans about all the giving, was that the people were so caught up in the zeal of giving to G- d, it had lost any connection to actually building the Mishkan; it had become about them, and their giving, rather than about G-d, and how to bring Hashem into the world.

(Which was why the fact that there was already enough to build the Mishkan was almost irrelevant. Kind of like the large Shuls one unfortunately sometimes encounters which have more plaques than people.)

So Moshe stops the giving, and reminds people not to forget the importance of becoming.

Which brings us back to this week’s portion. While that is a valuable lesson, it is also important, in the process of connecting (or re-connecting) to the ideals and goals of the project, not to forget the power and the importance of all of the details.

And this is a crucial part of life, which stands at the root of all our relationships and all of our dreams. Take, for example, the excitement of love, and that special time when you find that very special someone, and ‘love is in the air’. It almost seems that you can do anything, and that it doesn’t matter where you are or what you do, just as long as you are together.

But healthy marriages don’t last on walks in the park and candle-lit dinners. Because the garbage must be taken out every morning, the laundry has to get done, and the kids have to be taken to school with their lunches made each morning.

And before people get married, they often make time to talk about their shared dreams and goals, and what sort of a home they hope to build together. But they rarely get to think about who picks up the dirty socks, and what happens when the laundry basket is full at the end of a long day.

Most couples work these details out and come up with their own system for who does what when, and they often view this as a necessary part of a relationship, which is hopefully growing. And this is true in all relationships, whether between spouses, parents and their children, or even roommates. Whenever such relationships last, it is because the parties involved are willing to share the burden of all the chores and details that must be done to allow for the accomplishment of all the wonderful goals that were so ever present in the beginning.

The tragedy, however, is how much this approach loses along the way; because while this is all very true, it is also very sadly lacking.

Perhaps the point of this week’s parsha is that if the details are just “the burden of all the chores and details which must be done” as described above, then we are missing the most beautiful part of the process. The real challenge is to embrace the detail as part of a larger picture.

You can clean up the kitchen because someone has to do it, and you can even clean up your kitchen because you have been away for a while, and your wife works so hard, and how could you not at least clean up the kitchen? And if this is how you clean up the kitchen, then maybe you find yourself wistfully imagining how much more fun it would be to be walking your wife into a beautiful restaurant for a candle-lit dinner.

But you can also clean up the kitchen because you know it will bring a smile to your wife’s face, and the thought of her smiling when she walks out into the kitchen in the morning makes every dish you clean, into another rose in the vase. You can so infuse every detail of cleaning the kitchen, with the ideal of what you want your relationship to be about, that you actually transform your kitchen cleaning into a candle- lit dinner. (Though no one should assume this dispenses the need and the value of the occasional candle-lit dinner; it simply allows for candle-lit dinners on one level or another every day.)

And this is a part of what is going on here in this week’s portion of Pekudei. Because when Moshe blesses the people for the execution of all the details, what he is really valuing is the way in which all the details were done. Because if every shirt that gets folded is actually an act of love, then even if your wife is asleep while you are doing laundry, she is there with you all the time.

And when the Jewish people succeed in seeing G-d in all the details, then they have mastered the art of bringing G-d into the world, which is the entire point.

And this is what this portion is all about, here at the end of the book of Exodus. This book has three basic stages which are its theme.

First, the family of Israel, a family of brothers who sold their brother into slavery, becomes a nation made sensitive to human suffering by two hundred years of slavery. The beginning of the book of Shemot is all about the making of a great nation.

But that leaves the question: what is this great nation meant to do? They are given freedom, but what is that freedom for? So, the second part of the book is the recipe for how, with our newly acquired freedom, we can make a difference in the world: the middle of the book of Shemot is about the giving of the Torah. We acquire the mitzvoth, which are a blueprint for making the world a better place.

This leads us to the third piece: the goal of this recipe is not for us to find G-d beyond this world; the goal is to bring G-d into the world. The Jewish people have always been about making the world a better place by making room for G-d. And that is what building the Mishkan was all about. And if this week we conclude this process of creating space for G-d in our lives, then discovering the balance and the harmony between the power of the ideal, and the beauty of the detail is the crucial piece for making it all work.

And just as inculcating this idea into our lives on a personal level allows each of us to become a Mikdash Me’at, a living sanctuary for Hashem in this world, this is true also on a national level.

Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, in his article Zaronim, points out seventy years ago, that this idea is at the root of the transformation we are undergoing as a people coming home, and his observations are every bit as relevant today as they were when he wrote them.

Rav Kook was answering a challenging question: if indeed the return of the Jewish people to their homeland was the beginning of the fulfillment of the two-thousand-year-old dream of redemption as foretold by the prophets, why was this dream coming about through the likes of Theodore Herzl, David Ben Gurion, and Golda Meir, who while certainly visionaries and incredible individuals, were certainly not the rabbis of their day?

Indeed, some of the early Zionist leaders described themselves (whether we agree with their assessment or not) as being anti-religious! So why was G-d choosing them to be instruments of the fulfillment of His prophecies, if indeed this was the fulfillment of those dreams?

Rav Kook’s response is that there are two components to Judaism, which he calls the Clalim, or general principles, and the Pratim, or details of those principles.

If the Clal (general idea) is to “Remember the Sabbath day” which means to take the time to be in the moment and learn to let go of the process of trying to get there, the Prat (detail) is not stirring the soup on the fire, as it is a form of cooking. The ideal, that when I choose not to cook on Shabbat, I am letting go of my role as a partner in creating the world and getting back in touch with G-d who put me here as His junior partner in the first place, is the Clal. Trying to determine what actually constitutes cooking, and whether the item is fully or partially cooked, and how many degrees Fahrenheit will actually cause the action I am involved with to be an act of cooking, is the Prat (the detail).

The Clalim are all the beautiful ideals, dreams, and goals of Judaism: to love your neighbor as yourself, to pursue justice, and to honor one’s parents. And the Pratim are all the details, such as whether one is obligated to stand up when a parent walks in the room, and how much effort we actually have to make to return the scarf someone left on the bus.

For two thousand years, says Rav Kook, we took for granted that people knew and would not forget the Clalim. What the Rabbis were afraid of was that people would forget the Pratim. There was a need to ensure the survival of the complex system of details that make up the beauty that is Judaism. Because make no mistake about it, as beautiful as all the goals and ideal of Judaism are, unless they are infused into our lives every day, in every moment and in everything that we do, they will remain simply as ideals and will have very little impact on how the world behaves, much less on how the world could be. And that is not what Judaism is about. Judaism believes that while the idea of Tzedakah (giving charity because it is the right thing to do) is powerful, unless we are confronted with it every time we draw a paycheck and every time we harvest our field, it will remain forever simply a nice idea.

However, in the process of ensuring that the details would not be forgotten, suggests Rav Kook, we lost touch with the Clalim. We got so wrapped up in the details, we lost sight of the goals and the dreams, the beauty and the inspiration. And so the Jewish people finally rebelled, and in a desire to get back to the beauty of the ideals, they let go of the power of the details. Which is why the early builders of the State of Israel for the most part wanted nothing to do with the details of Judaism and halachah (Jewish law). Yet they embraced all the ideals of Judaism; they just gave them a new name: socialism, or communism. How sad, that in saving the baby, they not only got rid of all the bathwater, they threw out the bath as well.

We are living in a time when there is a genuine thirst for discovering the beauty and the power of the Pratim, the details that fuel the Clalim, the goals and dreams of Judaism.

And it is interesting that there are two very distinct groups in Judaism today that are struggling to re- discover the beauty and inspiration of Judaism in their lives.

There are those who have had very little to do with the Pratim and have little knowledge of all of the details of a Jewish way of life, yet they are infused with the Clalim and have embraced the ideals of Judaism. They are learning in seminars and life training sessions around the world, to be in touch with the moment, that loving is all about giving, and that we are all really one. But they are thirsty to discover how holding a kiddush cup on Friday night can be a living embodiment of all of those ideals, and have little knowledge of how one makes kiddush, what one says, and what the words mean.

And then there are those who have been making kiddush all their lives, who know the words, and what they mean, by heart, and who are often well versed on the debate as to whether one stands or sits, or a little of both, during the Kiddush, as well as whether one can use grape juice or wine, how big the cup should be, and what the correct way to hold that cup is. They are immersed in the details, the Pratim, but those details have lost their shine; and while the details are crucial, the inspiration and the beauty, the power and the joy has been lost. They are thirsty, sometimes without even realizing it, for the Clalim, the inspiration of meaning and joy, hidden in every detail of every ritual.

This then, is the challenge of this week’s portion: can we create again the Jewish people as it was meant to be, which sees the beauty and the value in both of these crucial components of Judaism.

And there is one more important piece to this puzzle. Because when we speak of the beauty of the detail, and the value of seeing the whole in each of the details and connecting with G-d through every last detail, this is true not only for the process of our building of the Mishkan; it is true for our identity as a people as well.

It is clear from a contextual perspective that it was the artisans and the wise men who actually physically built the Mishkan. But the Ohr HaChaim (Rav Chaim Ibn Atar) points out that in giving to the Mishkan, the Jewish people became partners in the building of the Mishkan. And most importantly, they were all blessed, and all viewed as equally crucial and important in the fulfillment of this mission.

The building of the Mishkan was accomplished every bit as much by the fellow who donated his gold tooth for the Mishkan, as by the artisan who actually fashioned the Menorah wherein that gold tooth found its final home.

And more important than seeing the value of every detail of the Mishkan was the challenge of seeing the beauty and the value of every ‘detail’, every last individual Jew, as part of the entire Nation of Israel.

Whoever we are, and whatever silly labels we seem to affix each other with, we are all, in the end, one Mishkan. There was no reform, conservative, orthodox, ultra-Orthodox, or even Conservadox section in the Temple; we all just hung out in the courtyard together. And this too, is the message of this week’s portion.

Moshe chooses to bless all of the people together, because a Mishkan is only a Mishkan if we are all one in viewing and building that Mishkan.

This is why, perhaps, Moshe could no longer enter the Tent of Meeting at the end of the portion, because the Mishkan was never meant to be about one man; it was about all of us. In fact, the glory of Hashem that descends on this world is the common soul of the entire people when we are capable of seeing Hashem in every person, regardless of their views and beliefs.

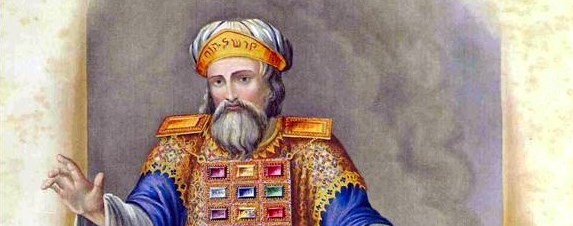

Hence only the Kohen, the High priest, Aaron, could enter the Sanctuary’s Holy of Holies: because he represented peace- shalom, which comes from the root Shalem, whole. Aaron was the living embodiment, as was the Jewish institution of priesthood, of an entire people, completely whole with each other. Indeed, G-d communicates to Aaron through the letters of the names of the tribes on the breastplate. Because it is only through recognizing the value of all of the tribes of Israel that we succeed in bringing G-d into this world.

And incidentally, this is why verse 32 appears in its strange format: “And all the work of the Mishkan (Tabernacle)- the Tent of Meeting, was completed, and the children of Israel did all that Hashem had commanded them, so they did.”

The Mishkan was not completed because the work was done; it was completed because the Jewish people were able to do it together, and because they succeeded in keeping the passion of the dream, while embracing the power of each and every detail necessary to complete their work.

We have a lot of building to do these days. Most people think we need to build fences and bomb shelters; but in truth we need to build bridges; the kind of bridges that let us meet each other up close. Maybe this will be the year where we finally get it. But it can only start when each of us, building our own personal sanctuaries, taps into the beauty of our dreams, while embracing the value of every one of us; every last detail.

Shabbat Shalom.